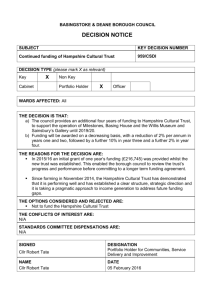

Document 11269357

advertisement