Raise the Roof: Can Location Efficient... Compact Development, and Transit Ridership?

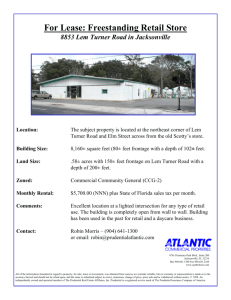

advertisement