YEAR 2012 14 March 2012 List of cases:

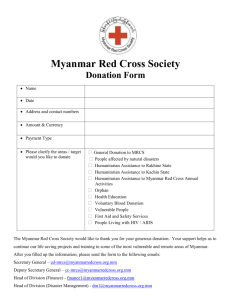

advertisement