CONCESSION BARGAINING Robert B. McKersie and Peter Cappelli

advertisement

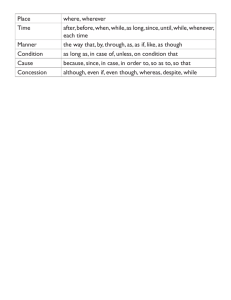

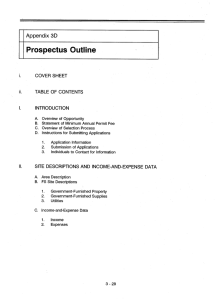

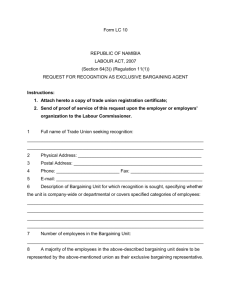

CONCESSION BARGAINING Robert B. McKersie and Peter Cappelli WP 1322-82 June 1982 Concession Bargaining How to Distinguish the Species Called Concession Bargaining We are in a period of very intense and widespread economic change. Concession bargaining is a development that has come to the fore as the Certainly, the modern industrial pace of economic change has accelerated. era has witnessed change on a continuing basis, what Schumpeter has called the "creative destruction" of capital. In other words, there is a continuous process of disinvestment and reinvestment of capital. For a variety of reasons, the current period has taken on the character of a convulsion rather than steady change that can be "taken in stride." Another term which characterizes the change and one that is a favorite of economists, is discontinuity; an abrupt change from one rate of capital redeployment to a different rate of redeployment. The current situation can be understood more clearly if we consider the role that expectations play in the changes. itself, contains inherent risks. Employment, like life Workers estimate their chances of keeping a job based on experience in the industry and their sense of the labor market as to what is happening comparable situations. While these expectations change over time, they are reasonably stable and provide the backdrop against which decisions about wages and other matters are taken. For example, labor leaders and union members as they press for better contracts are aware that over the long run the firm may respond by mechanizing and finding other ways to use less of the higher priced labor. Also, if a company announces that it is shutting down a facility, the response of the workers to this prospect will depend upon what they see as their alternatives for finding other work. -1- III When a discontinuity or shock of severe proportions hit, then "all bets are off," and expectations previously formed no longer accurately represent the situation and must be reshaped, a type of agonizing repraisal. This appears to be the situation in many industries today. Factors Precipitating the Convulsion or the Onset of Extensive Restructuring Since concession bargaining is just one adaptive mechanism to these convulsions it is useful to enumerate some of the forces and factors that have given rise to the extensive amount of economic change that is taking place across the world. One view is that we have reached the end of a long wave, a period of innovation and growth that has characterized many industries since World War II. Students of the Kontrief Cycle point out that such turning points are inevitable given the way in which innovation occurs, capital is accumulated, markets expand, and then there is a shift of economic activity to the "new shoots". Whether or not we subscribe to this mechanistic view of economic development, it is clear that there are fundamental changes occurring in many industries across the world. The transformations in production and employment are triggered by a variety of developments. In some cases, the trigger comes from new products, for example - radial tires; in some cases, from new manufacturing processes - like robots. In other cases, the fundamental change is organizational, for example, the rise of mini-mills in steel and new methods of killing and processing meat in the meatpacking industry. Certainly, the move to deregulate several industries such as airlines and over the road trucking in the States must be seen as a basic organizational change that has set significant forces for economic change in motion. -2- Superimposed on top of these technical and organizational changes is the development of world markets and world trade. In effect, we see a type of rationalization of industrialized economies that represent a type of a world division of labor. We cannot understand the pressures in the automobile, steel, and tire industries without reference to the development of world-wide markets. For other industries, there has been a drop in the world-wide demand for their products. steel industry. This certainly characterizes shipbuilding and the Whether these changes are temporary (cyclical) or more permanent (secular), it is too early to tell. Finally, the world-wide recession (bordering on what some people would call a depression) is also an important force in the overall picture. We are therefore witnessing a conjugation of developments and forces that together provide the biggest shock to expectations concerning employment security since the 1930s. Alternate Strategies for Dealing with Economic Dislocation At this point, it may be helpful to use a chart to illustrate the various mechanisms that are used in different countries for dealing with the prospect of economic dislocation: for the private and public sectors, for the stages of preventing job loss, staging the job loss or cushioning the job loss. The advantage of using this chart is that it puts concession and productivity bargaining in the a context of other strategies. One of the major points to be explained is why there is so much more concession bargaining taking place in the United States while the response to economic change in other countries has been in the other cells of the diagram. -3- I 111 e 0 OQ 0 ~ ~~~~~~~C r.; cn r 0 r-0 * 0 ct C tz t C ~ trtO ~ f~0) (AO Ort 0 O b-'.Cft (D' H.~ rt 0~~~DH0 0 ft 0D hH ti 0u 0 P1 i I-H, rrH H rtc 0 In P Ht 03 C00.. 4 O3 3 cn ( OQ mrtI'drt 0) rt 0M O rC 0 H. · HI ¢' ~m O3 " r m 04 0 rt 't 0 a 't t./6 rtm Pi( ;' ( 0 9c t .a, . LHt m rA~~~V OO fD o -- ,t ~ '4 0 O'Q CD 'Ort 0:~B f . 0 r 0) O() ~ 0P1H' t H( '1r3 0 01 r0 0 H~ 0 - Q0 C2 P1 n~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~c cn ' c~ 0 Hrt 0 o '40tt O o OQ cq ,..,r0n (D e,. ' C 0O t gx. o ^ '1 o t 0t o H 0 ft 0) 0 I.-I I - H. Q \ . ( 0vC) 4 *0 Q oO H r r ri QO 0 f ~r- 100 HC r 0 ft *' g 0 0 rt P Oo oa.oaO i >t i 0rt 'rt o0 ct :3C 0 ft M 1N m , 0 -, 0 t N I ft 0t H. oo P H,O, 9D o , i.~ H 0 Pt" 0 w9 0' P0 - -ft o O r> 0O o m09O rt 6 0 MlCH :m' mH M0 ;I 00~ m' O OH I,'II 00 o' tj H. C') HOwt0 - H , ,, cr 0 m H I PIH 0 Mi 0 om~~~~~~~~~~~~~ M~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~i ~ m r ot 00t P P1: o m 0 H~(o 0I QM 6Hpi IDP 0 O 0 m o 0 r M cflin ',-'* 0 0t0 0 "I oC M ~ -. CO 0-ft v A few general comments about the patterns may help our understanding of concession bargaining in the United States. Early on in the adjustment cycle, as the forces for economic change start to gather, there is not very much concession bargaining in any country. In the United States, this period was characterized by plant shutdowns, in Germany and Japan the approach was industry restructuring and efforts to redeploy the affected In Britain and workers in a variety of human resource planning techniques. to some extent in Canada, there was outright opposition to plant shutdowns, and in Britain especially, efforts to prevent the job loss by a variety of government support programs. As the crisis deepens and the reach of economic change goes deeper and wider into the fabric of the economy, the question then is: how do the parties respond? There are no easy generalizations. It is clear at this stage that there is considerable resistance to additional plant shutdowns. They cannot be justified on the basis of excess capacity. the core of the economy is under threat in some cases. It is clear that In some countries, unions and workers may respond to such situations in political terms. They demand that the industry not be dismantled and solidarity prevents any consideration of concessions that would weaken the established wage and benefit scale. How a union and its members respond is a function of the ideology of the union (class solidarity vs. business pragmatism) and the extent of bargaining power inherent in the situation. Unions in the United States do not enjoy as much bargaining power even in the industries where they have been traditionally strong in terms of the percent of the work force organized. In the rubber industry, for example, approximately 20% of tire production is now done in non-union plants, and in the steel industry the development of the mini-mills is making the steel workers' -5- -~~-"~ ~~" ~ ~ ~---·.-_ ...... .. III position vulnerable. The automobile industry is of particular interest because the UAW still enjoys a very strong position. Here, the choice for the union is between advocating a very strong protectionist position vs. engaging in concession bargaining in an effort to beat the competition in the marketplace. It is remarkable in terms of international comparisons of labor movement philosophy and outlook that the UAW has not done more than urge Congress to pass special legislation and to visit Japan to secure voluntary export agreements. Of course, the UAW is aware that the political climate in the United States, at least presently, has not been conducive to legislation that would protect industries like automobiles that are under the brunt of increasing imports. -6- CONCESSION BARGAINING IN THE TIRE AND AIRLINE INDUSTRIES Now, let us take a closer look at the process of concession bargaining. From the union's point of view, one might think of it as bargaining to save jobs; management is saying that they need lower labor costs in order to maintain employment, and they are asking the union either to do something about it or face unemployment. The key question for the union is whether management is accurately presenting their true situation. It may be helpful to look in detail at the experience of two industries, tire manufacturing and air transport, which in many ways span The tire industry the range of experience with concession bargaining. represents old-line manufacturing, while air transport represents a relatively new, service industry. Both have experienced shocks that have led their firms to threaten the security of current employment levels. The Tire Industry The story in tire manufacture is one of excess capacity in multiplant operations. Plants and local unions compete against each other to say open, and they do that through concession bargaining. The crisis was brought about by two developments which paralleled those in auto. there was a fall in the demand for domestic tires. OPEC price increases by driving less. lighter, fuel efficient cars. replacements. First, Consumers responded to When they bought cars, they bought Both developments cut down on tire wear and More importantly, the cars they bought tended to be imports, equiped with imported tires. Fewer original equipment tires were needed. The second change which began about 1970 was a shift in demand away from bias to radial tires. Radials have superior handling characteristics, and cars equipped with them get better gas mileage. In addition, most of the imported cars came equiped with radials; owners were likely to replace them with radials, too. -7- ___ III The industry responded to these developments beginning with the shift to radials. American manufacturers needed new equipment to manufacture radial tires, and they were faced with a choice of converting existing plants or constructing new ones. Certain areas in the U.S. were offering tax incentives for new plant construction (mainly in the South). This seemed to tilt the balance for tire manufacturers, and they constructed new radial plants almost entirely in the South (chart). Meanwhile, the North was left with the existing bias plants which continued to operate. The shift in demand toward radials continued; they increased from 2% of the tire market in 1970 to 55% in 1980. One result of this shift away from bias tires was the creation of substantial excess capacity in the Northern plants. These changes were accentuated by the OPEC price increases, particularly those in 1979. The subsequent decline in driving, the recession that followed the price increases, and the "radial effect" (the fact that radials need replacing about one-third as often and were coming to constitute the bulk of the market) produced a general decline in the demand for tires. The decline in the demand for bias tires was precipitous, and the resulting excess capacity in bias plants meant that some would have to close. Which plants should close? high-cost plants. An obvious answer was to close the At a plant level, local management and local unions had an incentive to lower costs in order to keep their plants from closing. There is some indication that higher-level management left the plants free to compete with each other to stay open. concessions at the plant level. They competed by securing It is an indication of the excess capacity -8- CONSUMPTION OF AUTOMOTIVE TIRES IN THE UNITED STATES (million units) PRODUCTION YEAR TIRE IMPORTS 1973 223 15 13 1976 190 16 14 1977 237 17 15 1978 230 17 17 1979 215 20 16 1980 168 18 16 -9- ----- TIRES ON IMPORTED CARS - ----- ---- NEW TIRE PLANTS Firestone, Decatur, IL 26.3 thousand tires/day. Goodyear, Union City, TN 47.0 Goodrich, Miami, OK 11.0 Goodyear, Lawton, OK 22.0 General, Waco, TX 20.6 Goodyear, Gadsden, AL 52.5 nonunion Firestone, Wilson, NC 20.0 nonunion Uniroyal, Admore, OK 36.0 nonunion 235.8 Industry capacity between 1960 and 1980 approximately 600-800 thousand tires/day. -10- CONCESSIONS - TIRE INDUSTRY YEAR STATUS AFTER CONCESSION LOCATION 1978 10/3/77 1/11/78 1/24/78 3/29/78 5/18/78 11/14/78 11/16/78 ?/?/78 Firestone, Akron Goodyear, Akron (Plant 1) Goodyear, Gadsten, AL Goodrich, Akron Seiberling, Barberton, OH Mohawk, Akron Mansfield, Mansfield, OH Uniroyal CLOSED CLOSED Open CLOSED CLOSED CLOSED CLOSED Sold General, Akron Goodyear, Akron (Plant 2) Mohawk, West Helena, AR CLOSED CLOSED CLOSED Goodyear, Los Angeles Uniroyal, Detroit General, Peru, IND Uniroyal, Chicopee Falls Firestone, Middlesville, IN CLOSED CLOSED Open CLOSED CLOSED Cooper, Texarkana General, Akron Mercer, Newark Firestone, Memphis Goodyear, Topeka Firestone, Akron Open CLOSING 1982 CLOSED Open Open CLOSED 1979 4/16/79 5/?/79 6/11/79 1980 2/4/80 2/10/80 6/27/80 7/7/90 10/30/80 1981 2/22/81 3/27/81 4/2/81 5/19/81 7/16/81 8/13/81 -11- `-`-"I~----~"---"--I----- III that virtually all of these plants closed eventually (chart). The plants that closed were all bias plants, and they were almost all in the North. There are no more tires being made in Akron, once the center of the industry. The Air Transport Industry This is a very different case -- price competition following degregulation forced revenue in some carriers below costs and brought them near bankruptcy. Before 1978, Government regulations restricted entry and made.it difficult to compete on prices and routes. After deregulation in 1978, new carriers were free to enter the market; the number rose from 38 to 80 between 1978 and 1981. Charter and intrastate carriers were able to compete with the main airlines on trunk routes. As a result, price competition increased substantially, especially on the well-travelled routes. The new carriers (and the charter and intrastate carriers) had substantially lower labor costs. scales. Most were nonunion, with lower salary All had younger crews with lower seniority pay. work out of their crews through tougher workrules. And they got more Southwest Airlines, for example, even though it is unionized, gets 50% more flight time from its crews than do many of the main carriers. Their labor costs are less than half; labor costs at smaller, regional carriers like Midway are two-thirds less. The older, established carriers still retained some cost advantages, particularly on longer flights where their larger planes cut average costs. The situation changed in 1979 when OPEC price increases doubled fuel costs (then about 30% of total costs). Because the demand for air transport is very sensitive to the business cycle, the recession that followed the OPEC increases led to a substantial fall in demand. -12- The situation got so bad in 1980-1981 that the demand for air travel declined absolutely for the first time since WWII. With all of this competition in the industry and with the absolute demand for transport declining,the market produced tremendous excess capacity (one estimate put the excess capacity on the North Atlantic route equal to 50 jumbo jets per day). The excess capacity led to price cutting on many runs and price levels often below costs. 1981 was the worst financial year in aviation history; fourth-quarter losses for the industry were $294.9 million. 1980 was the next-worst year, and 1982 is expected to be about as bad. (chart) Many of the carriers had loaded-up on debt just before this period, and the recent rise in interest rates particularly hurt those with short-term debt. The following airlines are in the worst position: Republic and Pan Am took on substantial short-term debt to finance mergers; Braniff also took on short-term debt to finance expansion; Western and Continental borrowed to fund new equipment. These airlines are all in danger of being unable to fund their current debts and of being reorganized or simply going under. Concessions in the airline industry will not make up the cost Prices are not advantage that the new carriers have on shorter flights. closely related to average costs on individual routes. So concessions do not help a carrier compete on the market; they are designed to free resources to service debts and meet capital requirements. This is clearly a different situation than in the tire industry. The pattern of concessions is straightforward. They have occurred this year because conditions now are the worst in history. Some carriers are doing rather well, some are near the brink, and most are somewhere in the middle. Although most are trying for concessions, those -13- _ · _sl ^1^1___ I'I AIRLINE CONCESSIONS PROFITS CARRIER CONCESSION -$ 31.4 mil Brainiff 10% pay cut and variale earnings plan through 1983. Contractual wage increases continue -$360. mil Pan Am 10% pay cut through 1982; contractual increases suspended; work rule changes -$ 66. mil Western 10% pay cut for six months, now in jeopardy as Teamsters have rejected it -- other groups may follow; pilots may agree to reduce labor costs to '82 level through productivity -$ 24.5 mil Republic 10% pay cut for clerical staff; one mo.t:1 pay deferral for pilots -- repaid by August; 10% pay cut for flight attendants may be extended to '82 -- currently in court -$ 43.5 mil Continental 10% pay cut from pilots -$ 49.9 mil Eastern Variable earnings plan -- employees contribute to offset losses up to a certain percentage -$148. mil United +$ 86.5 mil Delta +$ 72.2 mil American Productivity concessions from pilots; two-man crews on 727s No concessions No concessions -14- able to secure them are carriers who are worst-off, who are actually in financial danger. As with any other negotiation, concession bargaining can take place both at local and national levels. Bargaining at local levels requires that the firm have autonomous units -- the case in multiplant industries such as rubber, not the case in air transport. Although one hears more about negotiations at the national level, there is much more concession bargaining at the local level. It is natural to wonder why there are so many concessions now and why they are happening where they are. The short answer is not simply because of the recession but because of the structural change in the economy. The industries undergoing concession bargaining have experienced several years of severe structural change. Many industries have suffered excess capacity because of a permanent fall in demand (as in tires and auto). Some have seen the entry of large numbers of low-cost competitors because of deregulation (trucking and airlines). foreign competition (steel and autos). Others are damaged by low-cost These problems have led to a fall in the demand for the industry's product and a subsequent fall in the demand for labor; current levels of employment cannot be maintained at current cost levels because of the shift in demand. These problems have been building in many cases throughout the 1970s; the recession simply made them worse. What does management ask for in concession bargaining? They want to reduce labor costs, but there may be many ways to do that, not all of them equally easy. Certain items are more visible from the union's point of view and may also require more levels of approval. Management usually asks for work rules, scheduling changes, grading adjustments, wage and fringe freezes, and wage and fringe cuts -- in that order. -15- The first items are less visible and can usually be negotiated locally. The latter ones are more difficult to secure but cut costs faster. In general, will the unions agree to concessions? The different levels within a union-may have different interests in concessions. The Local should be particularly concerned with employment consequences when concessions bargaining takes place at the plant. The International may be more concerned with the effect of concessions there on the pattern, oil them spreading to other plants, and less concerned with the employment risk. Whether the union agrees to the concessions may, therefore, depend on which level makes the decision. And that differs with the issue -- workrules, for example, are usually left to the local level. It also differs with the union -- some may allow more autonomy at the local level. The key question for the union is whether management is serious in its threats. The Local and the International may have different information and perceptions regarding the truth of management's arguments. It may be the case that the International actually has to convince the Locals to take Management's claims seriously. Alternative employment prospects also influence decisions. There may be cases where skilled workers are willing to see a shop close rather than make any concessions because they are reasonably certain of finding jobs with equal compensation elsewhere. In the tire industry, there have been cases where the Locals have not granted concessions. granted them. In this recent period, they appear to have always The reason would seem to be that the union believes management to be serious in its threats, a conclusion re-enforced by recent experience, and that alternative employment prospects in the industry and in the region are dismal. clear. American, In airlines, for example, the picture is no so or example, could not get concessions from aIyone because -16- it did not appear to be in bad enought straights. On the other hand, even the Machinist's Union, which has a policy of opposing all concessions in principle, made an exception for Braniff because it was so obviously in trouble. One finds similar variance in other industries. Chrysler got concessions first, perhaps because they were in the worst shape; General Motors got them last (and apparently got least) because they appeared to be in the best financial position. Yet even at Chrysler, workers in the more successful plants were reluctant to go along with the concessions because they felt that their plants would continue to operate, perhaps under a different owner. Are the unions getting anything in return for the concessions? Sometimes they are, and this may be what is new about concession bargaining. But concessions are designed to cut labor costs, and it would be irrational for management to give back items that increase labor costs, such as work rules or wage and fringe improvements. traditional union goals. Yet these are the The real challenge here is for unions to look for improvements in other areas, such as union security arrangements, job security, future wage and benefit improvements, some say in management decisions, etc. In short, move into areas traditional considered management preogative. How much management is willing to give for the concessions obviously depends on how badly they want them. If they are simply rearranging production between plants, and the unemployment threat comes from that, management may not care that much about concessions. If the company is threatening to go out of business, however, they may want them quite badly. In the rubber industry, it was clear that many plants had to close, and there was little reason to believe that the companies cared which ones were shut down. In these local concessions, the union received virtually -17- 1__1__1_11______ __ __ nothing in return. But in national bargaining with Uniroyal, where the company was threatening to go out of business, the union secured a number of improvements, including the right to audit company books in return for wage concessions. In the air transport industry, the unions won a number of improvements in return for concessions, largely because the companies were actually threatening to close and desperately needed the concessions. Pilots at Western and United won no layoff clauses; workers at Pan Am and Western gained profit sharing; Republic employees took a stock swap as a concession. Where concession bargaining takes place, one might expect Lt to First, labor costs and employmeL permanently alter industrial relations. security will be more closely linked. Second, negotiations will increasingly include plant and firm characteristics, contributing to the break-up of contract patterns within and between industries. Finally, bargaining may extend into areas of traditional management perogative as the price for union concessions. Evaluation of Concession Bargaining Since the dust has not settled on this period of intense activity, it is not possible to discern what the net effect of these bargains will be. There is the cynical view that the whole business is a plot by management to gain the upper hand and to drive down the social wage. The other view, and the one to which we are more prone to suscribe, is that we are witnessing a period of inevitable economic adjustment. automobile industry in the United States. Consider the Rather than sticking strictly with a protectionist position, the union has been willing to join the issue and to put operations in the United States on a more competitive basis. -18- A very valuable lesson about maintaining economic viability on a world-wide basis has been driven home to many automobile workers. If the result (and this is a big IF) is to stem the tide of foreign imports and to not only protect existing jobs but to regain some lost employment, then this will promote a very strong reinforcement within the thinking of the U.S. labor movement. At a minimum, the willingness to mark time on cost of living and to give up the annual improvement factor and other gains means that the labor cost picture will be more favorable in the United States for Japanese manufacturers who might be contemplating making rather than shipping In other words, from the union's point automobiles into the United States. of view, there is the need to keep wage scales at a point where foreign companies are motivated to contemplate the possibility of producing their products in the United States. Of course, the union faces the challenge of organizing these workers, but the UAW is one union that has a good record of organizing new facilities that are brought on line in their industry. Returning to the main theme of positive adjustment, from a public policy point of view, it certainly is preferable for workers to make adjustments that reduce labor costs rather than holding firm and forcing companies to shutdown additional plants. From the viewpoint of future generations, a plant shutdown is a continuing loss. Workers who are willing to work longer hours and to work for less are making a contribution to the job viability of a community for the future. The important conceptual distinction is between viewing concession bargaining as an element of distributive bargaining, that is, whatever the workers give up is a direct gain to management (in this case, increased profits) versus some form of integrated or mixed bargaining, where both sides gain more than they give up. This latter case, of course, depends -19- _ III upon the elasticity of employment. If the concessions are sufficient to increase the volume of activity and to pull back into the economy work that has been exported to other countries, then the concession bargaining is indeed a case where both sides gain. Of course, there are situations where concessions have no possibility of increasing revenue, in the public sector for example. It is not surprising that in the face of financial cutbacks, unions in the public sector are not engaging in concession bargaining and are forcing management to lay workers off and to bargain through the changes on a distributive basis. The situations where there is the greatest chance of mutual gain are those where there is competition from the non-union sector or from abroad. Thus, tires, trucking, airlines, meatpacking, and autos all contain the possibility that concession bargaining may help the employment prospects in the unionized sector. Yet, even in these industries there are a number of examples where concession bargaining has taken place and it has not brought about the desired improvement in job security. This is because either the plant in question was so antiquated that it eventually needed to close and the concession bargaining was just buying time, or because a long-run situation overcapacity existed in the industry where some plants needed to be closed. The concessions did not move the particular plant in question far enough up the league tables to prevent a shutdown. Bridgeport Brass, for example, closed a plant in the fall of 1980 three years after the union involved agreed to a cut in wages and benefits of almost $1.30 an hour. Is There Anything New This Time Around With Concession Bargaining? A number of analysts, such as John Dunlop, maintain that what we are -20- witnessing today is just a re-running of an old movie. I think these commentators are right with respect to the side of the bargain that the company gains, namely wage reductions, work rule changes, increased time on the job. However, it is on the other side of the bargain, what workers gain, where there is some new ground, what might be called the latest frontier or what unions mean by "more". Let me enumerate these dimensions and make a few comments about what we see as interesting trends. 1. A look at the books. In a number of agreements management has said that it will show the union important financial data. For example, in the settlement last year between Armour and the Food and Commerical Workers Union, the company agreed to provide a five-year plan of capital expenditures and each January to provide a summary, plant-by-plant, of investment activities. In the Ford settlement, there will be meetings in which the company shares information about investment plans as they affect employment on a world-wide basis. In the case of one of the large airlines, information will be provided so that the Pilots Union can be sure that the productivity improvements that have been realized as a result of their concessions do not result in the layoffs of any pilots. (The company gave the guarantee that pilots not needed as a result of productivity improvements would be kept on board until attrition took effect.) 2. Union Security. In a number of agreements, unions have obtained important institutional gains. For example, Armour agreed to recognize the union in any new plant based on a check of authorization cards rather than forcing the issue to a representation election. -21- I____IIIYV______. In trucking, there are some limitations on the establishment of non-union subsidiaries - in other words, a deterrent to further development of the double-breasted trucker. 3. Job-investment bargaining. One of the most interesting developments has been the coupling of employment security with investment behavior on the part of the corporation. In a number of significant situations, such as in the paper industry, at General Electric's Erie operations, Goodyear in Topeka, Timken for its Canton plant, a commitment has been made convening investment dollars as part of the concession deal. Perhaps the word bargaining is too strong a term to describe the deal because the unions are not writing into the contract any information about a company's decision to modernize its facilities. Rather, it is a linkage, a type of coordination across the employment and investment themes. It is somewhat analogous to what happens when a community goes all-out to attract a new facility of a company. The community makes tax concessions or provides some other inducements -- with the promise by the company to put new jobs in the locality. Nothing is legally binding but it is understood that the coordination will take place because it is in the interest of both sides to go through with the understanding. Similarly, we see a development of this sort in the context of concession bargaining. Whether U.S. unions will push it to the next step of filing complaints through arbitration or through the courts if they feel a company has renigged on its side of the bargain remains to be seen. But in any event, we appear to be moving into a new -22- era where unions are much more interested and sensitive about the investment decisions that companies are making. 4. Enhanced job security. Given the prominence of this subject in negotiations in the U.S automobile industry, this is clearly one of the significant dimensions of concession bargaining. It is rather complicated and a number of points need to be made. First, even if job security is not made explicit, it certainly is involved implicitly in any concession bargaining because the presumption is that by lowering labor costs, then more business will be attracted and jobs will be made more secure. A number of important assurances have been given by companies with respect to job security. In terms of the diagram used earlier, a number of them have been willing to move to the staging category rather than continuing the abrupt process of shutdowns on short notice. Thus, several companies have said they will not shut any additional plants down for one or two years and if they do they will give at least six months advance notice. Ford has gone further and has said that if there are excess workers it will endeavor to handle the problem through attrition. The other dimension of job security is a guarantee against layoffs. Ford will experiment with this for two plants where 80% of the workers will be kept on regardless of production levels. Similarly, United Airlines has agreed to not lay off any of its pilots (in exchange for major changes in availablility of pilot time). These assurances go a long way in the direction of what has come to be known as the Japanese method of career employment -23- I III -- also, practiced by a number of high tech firms suchl as IBM and Hewlitt Packard. There are several questions concerning this trend. How far can a company go in guaranteeing no layoffs when it is not in control of its market position or the demand for its product? Ford can achieve no-layoff for several plants but it may be at the expense of moving work into those plants from other places, thereby having a secondary effect on job security of other workers. While a company can use human resource techniques to even-out the ups and downs and to avoid layoffs that are part of the cyclical activity of the industry, it cannot go so far as to avoid layoffs if the demand is not there for the product. The second major question has to do with the preference of the workers who are in the industries we have just cited. What preference do they put on stability of employment as contrasted from earlier patterns of work interrupted by periods of idleness? It is not clear that such a pattern of work-alternated-by-leisure leads to lowered productivity by itself. What does lead to such behavior is fear of permanent job loss, and as we were saying above, assurances against that are things that most companies cannot give. The in-between category and where commitments about no layoffs do make sense is where technology has changed and companies initiate discretinary adjustments, such as major reorganizations. This is where there can be considerable resistance to change, and by using human resource planning techniques, phasing in the changes, and not laying workers off, there is a much greater likelihood that -24- these changes will be introduced, accepted and incorporated more readily, helping the competitive position of the company. 5. New values. It is clear that the designers of a number of the concession agreements are attempting to set in place the new values of openness, equality of sacrifice and egalitarianism. Whether these values will "take" or are just the expressions of the philosophy of the people at the top remains to be seen. In the work by Athos and Pascale it is estimated that to change the values of an organization in a radically different direction takes a minimum of ten years. But in any event, some forces have been set in motion that may move some companies and some industries in the direction of what has been called in the literature, Theory Z. The Dilemma For Labor Leaders The economic crisis and the possibility of concession bargaining pose incredibly difficult dilemmas and decisions for union leaders. They find themselves in a type of no-win situation. This maybe called the predicament of participation. Helping shape business decisions presents an acute problem for union leaders and worker representatives. They find themselves in a dilemma with sharply drawn disadvantages on each side. On the one hand, if they become involved, they may be viewed by the rank and file as having been co-opted by management and thereby suffer the stigma associated with business demise. These fears are well illustrated by the experience of some of the unions in British Steel who have been blamed by rank and file members and community representatives for having gone along with the decisions that have dismantled a large part of the steel making capacity. -25- 111_____ Worker Directors, who have been "associated" with the decisions have been treated as strangers in their home territories. On the other hand, if union leaders do not get involved to challenge the business decision, they may also be condemned; an illustration comes from the United States. The United Automobile Workers represented approximately 1,000 workers at a Dana Corporation plant in Wisconsin making front-end axles. In a survey conducted among the workers about a year after the plant closed down, the workers expressed many more negative feelings about the union than about management. The workers viewed management as having made an inevitable decision to close the plant down in the face of a drop in demand that hit the vehicle industry. However, the workers felt that the union should have done more to force the company to transfer other work into the plant or to have put pressure on the company to close another plant. Union representatives were seen as having failed in their tasks, since it is their responsibility to make job security a number one objective. If job security is not pressed, then there can be a substantial backlash against union leaders. During the early stages of the adjustment cycle, labor leaders may be able to "look the other way" in hopes that the problem will go away, or if local rank and file people enter into adjustments on their own, then they can ignore the impact at the national scale. This is the approach that the Teamsters had taken until recently. When the crisis becomes severe enough that national leaders have to move into the picture, they must guage how much of the crisis is cyclical and how much is permanent (unless some changes are made in labor costs). This is very much a judgement and puts them in the impossibly difficult position of trying to estimate the future fortunes of a given company, -26- industry, and economy. In the short run there is no easy solution. Over the long run, the only way for union leaders to get out of the bind that such a defensive position always poses for them is to take the initiative on a country-wide or indeed on an international basis to organize the market and to take the wage rate out of competition. Thus, after this crisis is over, we can expect to see much more activity across industrialized countries by the international trade union confederations. Our view is that they are biding their time on the question of multi-national bargaining and that once economies begin to pick up strength, unions will be moving to avoid a repetition of the present situation by standardizing wage rates and conditions as much as possible. The Next Time Around Of course, efforts to establish a labor standard may prevent wholesale concession bargaining, but ultimately pressure will come from some sector, if not from an underdeveloped economy then from a new industry with a better idea and a lower cost product. The interaction between achieving wage gains and wage adjustments is dynamic. In some respects, concession bargaining has been more intense in those industries that have enjoyed stability as a result of the union scale and collective bargaining. The workers have been immunized from concern about labor costs because the seniority principle enabled most workers in the industry to count on continuing employment. Certainly, the recent pressure in collective bargaining for cost of living clauses must be seen as having been otherwise. In unorganized industries where everyone is at risk, there may be more interest in keeping the operation competitive. By contrast, in industries that have not been as strongly organized, such -27- III as garments and textiles, concession bargaining has not been as necessary precisely because the threat on a continuing basis of nonunion products has kept wages and benefits in line with competitive conditions. that wages have been kept on the low side. It is true But from a long-run view, it would seem that accommodation has occurred on a more gradual basis -rather than a long period of stability followed by a crisis and a very tough shake-out of the sort that is happening in a number of industries today. George Shultz uses the example of the dam and the buildup of water to illustrate this change. One can have a gradual runoff or one can hold back the pressure for an extended period of time only to have a complete breakdown and a flood where everyone "runs for cover". Another fact of life is that where wages have been taken out of competition, management also goes "asleep" and stops scanning the horizon for information about what is going on elsewhere in the industry. Both sides become overly complacent. The trick is to achieve a balance of stability and change -- neither extreme is functional. In collective bargaining we have the concept of the living document, a term first used by the UAW in the early 1950s. Both the employment relationship and the competitive position of the business need to subscribe to this dielectic of continuity and change. -28- I