Order, Authority, & Identity:

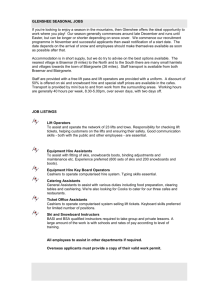

advertisement