TE Faculty Retreat 5/9/11

advertisement

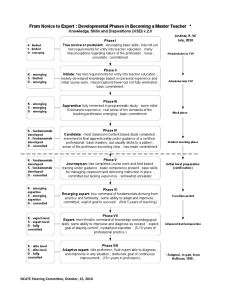

TE Faculty Retreat 5/9/11 A knowledgeable, skillful, commi4ed, and reflec7ve professional, in any domain, field or discipline, is, arguably, by defini7on, an expert. Although our candidates cannot be expected to leave WIU as such in completed form, by understanding what the process of a4aining exper7se entails, we will know and understand what we need to do to facilitate, or make more likely, that our candidates will develop into expert teachers in the long run. To the extent that we accomplish this aim, we are empowering our candidates. “As differences between experts and novices accumulated in educa6on and other fields, it became apparent that there was a need for a theory of development to describe the transi6on from novice to expert.” ‐ Berliner, D. C. (2004). Describing the behavior and documenFng the accomplishments of expert teachers. Bulle%n of Science, Technology & Society, 24, 1, 200‐212. “It would be helpful if there were predictable phases of teacher development that could guide educators.” ‐ Hammerness, K., Darling‐Hammond, L., Bransford, J, Berliner, D., Cochran‐Smith, M, McDonald, M. & Zeichner, K. (2005). How teachers learn and develop. In, L. Darling‐ Hammond & J. Bransford, Eds. Preparing teachers for a changing world: what teachers should learn and be able to do. Jossey‐Bass. From Novice to Expert: Developmental Phases in Becoming a Master Teacher (Adap7ve Expert)* We present, in what follows, a rela7vely well‐defined concep7on of professional development as the path to becoming a master teacher. In so doing, we do realize that the “real world” is a less well‐defined, and well‐ behaved place than what the model we will present would indicate. Students enter the Teacher Educa7on program at various points in their educa7onal development, and some meander over the educa7onal landscape in apparently random fashion (oKen blamed on the ins7tu7on, or department, or some other convenient en7ty). Some will progress more slowly, some more quickly, and some not at all. Others will progress and then plateau. Nevertheless, most will follow a path something like what we describe, and having a rough concep7on of where a student will, or should, be at par7cular points along the path can be helpful to students, advisors, and faculty as we work together toward the goal of producing competent beginners in the profession of teaching. It is also, we believe, of considerable value to have a (rela7vely) clear concep7on of the ul7mate target to guide us along the way. 1 TE Faculty Retreat 5/9/11 Postulant 1. A person submi>ng a request or applica6on; a pe66oner. 2. A candidate for admission into a religious order. Ini7ate 1. One who is being or has been iniFated. 2. One who has been introduced to or has aCained knowledge in a par6cular field. Appren7ce 1. One bound by legal agreement to work for another for a specific amount of Fme in return for instrucFon in a trade, an art, or a business. 2. One who is learning a trade or occupa6on, especially as a member of a labor union. 3. A beginner; a learner. Candidate 1. A person who seeks or is nominated for an office, prize, or honor. 2. One that seems likely to gain a certain posi6on or come to a certain fate: young actors who are candidates for stardom; a memorandum that is a good candidate for the trash can. Journeyman 1. One who has fully served an appren6ceship in a trade or craG and is a qualified worker in another's employ. 2. An experienced and competent but undisFnguished worker. Expert 1. A person with a high degree of skill in or knowledge of a certain subject. 2. a. The highest grade that can be achieved in marksmanship. b. A person who has achieved this grade. *Excerpted from The American Heritage® DicFonary of the English Language, Third EdiFon © 1996 by Houghton Knowledge – Comes in three forms – declara6ve (factual; conceptual understanding and integra7on); procedural (see skills); condi6onal (range of applica7on; situa7onal awareness). Declara7ve knowledge is a necessary condi7on for higher order thinking and problem‐solving. Condi7onal knowledge is cri7cal for the development of adap7ve exper7se and is enhanced where and to the degree an individual has developed a principled (theore7cal) understanding of the core concepts that define a domain. In addi7on to basic skills, included are professional knowledge as well as knowledge and understanding of context, content, pedagogy, and content specific pedagogy. Mifflin Company. Electronic version licensed from INSO CorporaFon; further reproducFon and distribuFon in accordance with the Copyright Law of the United States. All rights reserved. Skills – “The ability to use content, professional, and pedagogical knowledge effec6vely and readily in diverse teaching se>ngs in a manner that ensures that all students are learning.” – NCATE Professional Standards Handbook. Here we are in the domain of procedural knowledge which defines the type and level of skill(s) one has a4ained. This type of knowledge, too, exists in different forms on a con7nuum from the rudimentary capacity to slowly, and with great effort, work through a series of steps, to highly automa7zed, coordinated, yet flexible and adaptable performances. Teachers must somehow integrate content specific, social‐cultural, and pedagogical skills into a single, fluid, coordinated, and adap7ve performance. Disposi7ons – “Professional a>tudes, values, and beliefs demonstrated through both verbal and non‐verbal behaviors as educators interact with students, families, colleagues, and communi6es. These posi6ve behaviors support student learning and development.” Commitment, for us, is treated as an overarching disposi7on. Commitment reflects the degree to which individuals invest themselves in the pursuit of a goal, or set of goals. Other disposi7ons may be locally defined but must include (for NCATE accredited ins7tu7ons at least) fairness and the belief that all students can learn. This area may also include mental disposi6ons (e.g., reflec7ve, analy7cal, open to improvement). The ul7mate ques7on for us is: to what degree is an individual commi4ed to such disposi7ons, and to becoming the best teacher possible? 2 TE Faculty Retreat 5/9/11 Prepara7on for Teaching “…evidence…suggests that teachers’ development is influenced by the nature of the prepara7on they receive ini7ally…” – Hammerness, Darling‐Hammond, Bransford, Cochran‐Smith, McDonald & Zeichner, 2005. This individual has taken the next step. His, or her, professional knowledge and understanding of core subject ma4er (or domain, if secondary educa7on) is deepening. The focus turns to acquiring pedagogical knowledge, skills, and disposi7ons as individuals are ini7ated into the tasks, challenges and commitments they will confront as future teachers. The ini7ate has met requirements for entry into teacher educa7on, has a loosely developed, emerging knowledge of the profession based on personal experience and ini7al course work, his misconcep7ons are fewer but not fully eliminated, and he has made a basic commitment to enter the profession. Given that his/her basic skills and general knowledge base are well developed, the focus turns to developing deep content specific knowledge as well as a sound professional core, and preliminary development of pedagogical skills. The ini7ate possesses an emerging understanding of learners and learning, the importance of cultural context and background, and related core professional knowledge. At this level we are dealing with an individual who thinks he/she might want to become a teacher. Of course, different individuals come with different backgrounds, but these individuals typically share a naïve concep7on of the profession and their level of commitment is not yet deep. The primary focus of this phase should be on the development of basic skills to the highest level possible, and perhaps acquiring a general understanding of the nature and expecta7ons of the teaching profession. In terms of knowledge, skills, and disposi7ons, we want students to be developing high levels of literacy and numeracy, a broad and general knowledge and understanding of science, literature, history, different cultures, etc. The abili7es to read, write, compute, communicate, and reason should be clearly established and well developed. Lastly, we look for an overall commitment to learning and self‐ improvement in general that is consistent and goal oriented. “Metacogni6on is an especially important component of adap6ve exper6se.” ‐ Hammerness, K., et. al. (2005). Having acquired some pedagogical training, content specific understanding, and a basic grasp of the social, cultural, professional and ethical challenges of classroom life, the appren7ce is prepared to begin working in the classroom under supervision. The focus now turns to prac7cal applica7on of the knowledge and skills acquired in the classroom to real situa7ons and sefngs that approximate the demands of the profession. Most misconcep7ons (though not all) regarding the profession are now gone and the appren7ce is in the process of becoming aware of the reali7es of the demands of the profession. Beyond acquiring many basic rou7nes, developing the mental habits of self‐analysis, self‐explana7on, and self‐monitoring during this phase are cri7cal in terms of the long‐term development of teachers. 3 TE Faculty Retreat The candidate has accumulated the knowledge and skills, and developed the disposi7ons, needed to enter the profession of teaching. He/she has had the opportunity to apply the knowledge, skills, and disposi7ons he has acquired in increasingly complex field sefngs and is prepared to manage the demands of a classroom at a rudimentary level using basic rou7nes developed during student teaching and learned in the classroom. However, the ability to improvise and adapt to unusual circumstances is limited and underdeveloped. Equipped with the right habits of mind and disposi7ons, the candidate, with appropriate support and mentoring, can navigate the complex world of the classroom successfully. The candidate has accomplished all that is necessary to be worthy of ini7al cer7fica7on. The candidate is transformed into a journeyman when he/she begins working in a classroom of their own, or for which he/she has been assigned primary responsibility. Although the basic skill set is not fundamentally different from that of the candidate, the journeyman has accepted responsibility for a classroom and has entered the real world of his/her profession. The experience can be transforma7ve and only now has the real test of the individual’s commitment and quality of prepara7on begun. Possibility has given way to actuality, but the outcome is yet to be determined. If (!?) one’s prepara7on has been sound, the proper habits of mind have been developed, and the suppor7ng structures are present, the outcome will likely be propi7ous. 5/9/11 Transi7on to Teaching & the Route to Exper7se “…the number one quality believed to be necessary for training unusually high levels of performance was the desire to be excellent…mo6va6on may be more important for achieving success than talent.” ‐ Berliner, D. C. (2004). “So a reasonable answer to the ques6on of how long it takes to acquire high levels of skill as a teacher might be 5‐7 years, if one works hard at it.” – Berliner, 2004. The emerging expert has a4ained true command of fundamentals deriving from prac7ce and familiarity. They are fully commi4ed and have an explicit goal to succeed. Such an individual has had the opportunity to repeatedly apply his/her knowledge and prac7ce his/her skills in actual sefngs of prac7ce, some7mes singly, some7mes in coopera7on with others, thereby developing a personal, experien7al knowledge base to add to their previous educa7onal and training experiences. The result is the emergence of both a substan7al degree of automa7city in the applica7on of skills and some flexibility in dealing with variability of students and condi7ons of prac7ce. Condi7onal knowledge and awareness is growing as well. This phase may be cri7cal for determining whether or not the individual achieves adap7ve exper7se or his/her exper7se remains bounded (approximately 50% of prac7cing teachers achieve this level). 4 TE Faculty Retreat “… a con6nuing set of studies in and out of educa6on informs us that exper6se is quite oGen circumscribed.” ‐ Berliner, 2004. The expert teacher has achieved a flexible command of content and pedagogical skills and possesses substan7al ability to improvise as well as to diagnose student learning. Expert teachers have several explicit goals: (1) staying current in their field and (2) maintaining their pedagogical skills. Classroom rou7nes are well established and highly polished (fluid) under standard condi7ons. However, this kind of exper7se oKen has some limita7ons. That is, for many individuals, exper7se remains bounded (crystallized); an exper7se, that is, 7ed to familiarity with their students, materials, and their sefng (5‐10 years of professional prac7ce; approximately 20‐25% of prac7cing teachers achieve this level). 5/9/11 “… there are indica6ons from the literature that…a dis6nc6on exists between adap6ve exper6se and a more restric6ve kind.” ‐ Berliner, 2004. The adap7ve expert is an elite performer, a fluid expert able to diagnose, improvise, and func7on successfully in virtually any classroom situa7on. Years of deliberate, focused prac7ce, passion for the profession, deep social and cultural awareness, and the quest for con7nued learning and improvement, have developed and polished, a set of flexible, rou7nes and problem‐solving skills that have taken this individual to the top of the profession. Adap7ve experts also have the deliberate goal of con7nuous improvement. Their level of skill makes their performance in the classroom appear natural and easy. This, however, disguises the years of focused effort and deliberate prac7ce required to arrive at this level (10+ years in profession; perhaps 5‐10% of prac7cing teachers achieve this level). The novice to expert framework not only opera7onalizes our Conceptual Framework, it provides a shared perspec7ve for all involved in teacher prepara7on at Western. The only way in which we will accomplish the loKy goal of producing candidates prepared to enter the teaching field with the knowledge, skills, and disposi7ons that will make the development of exper7se likely is to work together and integrate our various programs, courses, etc. such that they all facilitate the achievement of the same aim. Not every candidate will be, or is expected to be, iden7cal as they will teach at various levels, various types of content and skills, etc. However, they should all share a strong commitment to becoming an expert teacher, with all that entails. Our task, together – as advisors, founda7ons instructors, methods instructors, content area instructors, field and student teaching supervisors, etc. – is to make sure that happens. It’s much more likely to happen if we share the same vision, understand one another’s roles, and work together as a team. 5 TE Faculty Retreat 5/9/11 Alexander, P. A. (2003). The development of experFse: the journey from acclimaFon to proficiency. Educa%onal Researcher, 32, 8, 10‐14. Barneg, S. M. & Koslowski, B. (2002). AdapFve experFse: Effects of type of experience and the level of theoreFcal understanding it generates. Thinking and Reasoning, 8 (4), 237–267 Bereiter, C. & Scardamalia, M. (1993). Surpassing ourselves: an inquiry into the nature and implicaFons of experFse. Chicago, IL: Open Court. Berliner, D. C. (2004). Describing the behavior and documenFng the accomplishments of expert teachers. Bulle%n of Science, Technology & Society, 24, 3, 200‐212. Berliner, D. C. (1994). The wonder of exemplary performances. In, J. N. Mangieri and C. Collins, Eds. Crea%ng powerful thinking in teachers and students. Ft. Worth, TX: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Darling‐Hammond, L. (2006). ConstrucFng 21st‐century teacher educaFon. Journal of Teacher Educa%on, 57, 10, 1‐15. Dreyfus, H. L. & Dreyfus, S. E. (1980). A five‐stage model of the mental acFviFes involved in directed skill acquisiFon. ORC‐80‐2. OperaFons Research Center, University of California, Berkeley, pp. 1‐18. Dreyfus, H. L. & Dreyfus, S. E. (1986). Mind over machine. NY: The Free Press. Ericsson, K.A., Charness, N., Feltovich , P.J.. & Hoffman, R. R. Eds. (2006). The Cambridge handbook of exper%se and expert performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Hoffman, R. R. (1998). How can experFse be defined? ImplicaFons of research from cogniFve psychology. In R. Williams, W. Faulkner, & J. Fleck (Eds.), Exploring exper%se: issues and perspec%ves. New York: Macmillan. Hammerness, K., Darling‐Hammond, L., Bransford, J, Berliner, D., Cochran‐Smith, M, McDonald, M. & Zeichner, K. (2005). How teachers learn and develop. In, L. Darling‐Hammond & J. Bransford, Eds. Preparing teachers for a changing world: what teachers should learn and be able to do. Jossey‐Bass. Hatano, G. & Oura, Y. (2003). Reconceptualizing school learning using insight from experFse research. Educa%onal Researcher, 32, 8, 26‐29. 6