Fly Away Home: Tracing the Flying African Folktale Honors Thesis

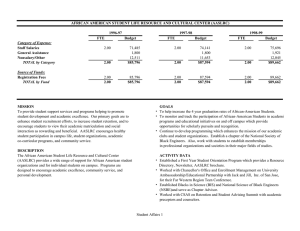

advertisement