The World Bank at 75 Scott Morris and Madeleine Gleave Abstract

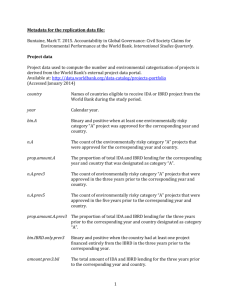

advertisement