The Future ofthe Industrial Community: S. B.A, History 1990

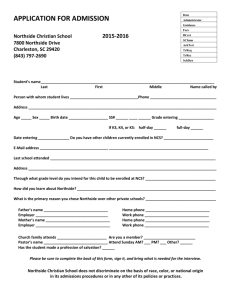

advertisement