Document 11158491

advertisement

stzs,

UB&j&ms

^Tt<^

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium

Member

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/hysteresiseuropeOOblan

working paper

department

of economics

"Hysteresis and the European Unemployment Probl em

by

Olivier

Blanchard

and

Lawrence H. Summers

Number 427

J.,

April 1986

massachusetts

institute of

technology

50 memorial drive

Cambridge, mass. 02139

"Hysteresis and the European Unemployment Problem

by

Blanchard

and

Lawrence H. Summers

Olivier

Number 427

J.,

April 1986

.mm

w

R€CEIV£D

-

^W "

..

-

.,.\ j;-j

April

19B6

Hysteresis and the European unemployment problem

Olivier

*

HIT and NBER,

J.

Blanchard and Lawrence

H.

Summers

*

and Harvard and NBER respectively.

We have benefited from the hospitality of the Center tor Labour Economics at

the LSE. Richard Layard has been especially generous in helping us in a variety of

ways. We thank David Grubb, John Martin and Andrew. Newel 1 for providing us with data,

and Michael Burda, Robert Waldman, Changyong Rhee and Fernando Ramos for research

assistance. We thank Stanley Fischer, David Metcalf, Steven Nickell, James

Poterba and Andre Shleifer and participants in the NBER macro conference at which

this paper was presented for useful discussions and comments.

Abstract

European unemployment has been steadily increasing for the last

expected to remain very high

this -fact

many years to come.

•for

In

this paper,

15

years and

is

we argue that

implies that shocks have much more persistent effects on unemployment than

standard theories can possibly explain.

persistence,

We

develop

a

theory which can explain such

and which is based on the distinction between insiders and outsiders

wage bargaining.

We

insiders and firms,

argue that

H

in

wages are largely set by bargaining between

shocks which affect actual

unemployment tend also to affect

equilibrium unemployment. We then confront the theory to both the detailed -facts of

the European

situation as well as to earlier periods

such as the Great Depression

in

the US.

of

high persistent unemployment,

After 20 years

negligible unemployment, most

of

since the early 70's

protracted period

a

unemployment peaked

United Kingdom

has risen almost

high and rising unemp oynent

1

3.3 percent

at

Western Europe has suffered

1945-1970

over the

continuously since 1970, and now stands at over

Common Market nations as

1970 and

of

of

19B0 and has

a

whole,

12

In

.

the

period, but

percent.

For

the

the unemployment rate more than doubled between

again doubled since then.

decline in unemployment over the next several

Few forecasts call

years,

and

none call

for

for

a

significant

its return

to

levels close to those that prevailed in the 1950's and 1960's.

These events are not easily accounted for by conventional

macroeconomi

c

theories.

classical

or

Keynesian

Rigidities associated with fixed length contracts, or the

costs of adjusting prices or quantities are unlikely to be large enough to account

for rising unemployment over

periods of

decade or more.

a

And

substitution in labor supply is surely not an important aspect

downturn.

The sustained upturn

in

intertemporal

of

such

a

protracted

European unemployment challenges the premise

most macroeconomic theories that there exists some

"natural"

or

of

"non-accelerating

inflation" rate of unemployment towards which the economy tends to gravitate and at

which the level

consideration

of

of

inflation remains constant.

alternative theories

of

"hysteresis" which contemplate the

possibility that increases in unemployment have

of

The European experience compels

a

direct impact on the "natural" rate

unemployment.

This paper explores theoretically and empirically the idea of macroeconomi

hysteresi s--the substantial

shocks on unemployment.

We

Our

persistence

of

c

unemployment and the protracted effects

of

particular motivation is the current European situation.

seek explanations for the pattern of high and rising unemployment that has

prevailed

in

Europe for the past decade and for the very different performance

of

the

labor market

in

the United States and Europe,

and reach some tentative conclusions

about the extent to which European unemployment problems can be solved by

expansionary demand policies.

The central

hypothesis we put forward

is

that

hysteresis resulting from membership considerations plays an important role in

explaining the current European depression in particular and persistent high

general.

The essential

unemployment

in

assymetry

the wage setting process between

in

who are want

A

insiders who are employed and outsiders

view to

a

Shocks which lead to reduced employment change the

oi

is

Section

the equilibrium unemployment rate

to •follow the actual

organized as follows!

1

documents the dimensions oi the current European depression.

United Kingdom over the past century,

It

Section

of

2

It

then considers

unemployment could

the United States and

high unemployment is in tact often quite

be

a

number

mechanisms through which high

of

generated.

explores what we find the most promising

for generating hysteresis.

shocks can have

that

in

a

It

presents

a

formal model

permanent effect on the level

are set by employers who bargain with insiders.

of

of

the possible mechanisms

illustrating how temporary

employment in contexts where wages

Persistence results in this setting

because shocks change employment and membership in the group of insiders,

influencing its subsequent bargaining strategy.

and whether

It

reviews standard explanations of the current European situation and

finds them lacking.

persistence

unemployment rate.

evidence consistent with our hypothesis are adduced.

documents, by looking at the movements in unemployment

persistent.

giving

hembership considerations can therefore explain the general

number of types of empirical

The paper

fundamental

insiders and thereby change the subsequent equilibrium wage rate,

rise to hysteresis.

tendency

a

Outsiders tre disenfranchised and wages are set with

jobs.

insuring the jobs of insiders,

number of

point is that there is

We

thus

then discuss the role of

such effects can arise in non union settings.

unions

Section

hysteresis.

3

It

examines the behavior

d

f

pott

war

presents direct evidence on the role

wages and employment and on the composition of

experience quite consistent with our model.

much more so than the US.

are well

Europe

High unemployment

unions,

unemployment.

on

We

theory

of

the behavior

of

our

of

find the European

Europe appears to have high hysteresis,

in

explained both by different sequences

and by different

of

light

in

Europe end low unemployment

of

especially

shocks,

in

in

the

the US

19B0's,

propagation mechanisms, with Europe exhibiting more persistence than

the US.

Section

4

returns to an issue which is of fundamental

Granting that Europe has more hysteresis than the US,

is

is

importance for policy.

it

really due to unions or

hysteresis itself endogenous, being triggered by bad times

?

In

an

attempt to

answer this question, the section compares Europe now to Europe earlier when

unemployment was low, and compares the current European depression to the US Great

depression.

This last comparison is especially important,

to drastically decrease

demand

unemployment in 1939 and 1940,

given the ability of the US

mostly through aggregate

.

The conclusion summarizes our beliefs and doubts,

our analysis for

policy.

and draws the

implications

of

h

1

.

We

e

T

Reco r d

of

Persistent Unemployment

start this section by documenting the dimensions of the current European

depression.

We

then demonstrate that persistently high unemployment like that

experienced

in

Europe at present

century suggest

a

is

not historically unusual.

surprisingly high degree

United States and United Kingdom.

We

of

Data for the past

persistence in unemployment in both the

argue that such persistence is not easily

explained by standard natural rate theories and conclude that theories which allow

for

hysteresis, by which we mean

past unemployment',

1

are required

to explain

such persistence.

The European Depression

.1

Table

1

presents some information on the evolution

major European countries as well

unemployment rates

States,

very high dependence of current unemployment on

a

the

in

1

unemployment rates

unemployment rates.

960

in

'

s

as

of

unemployment in three

the US over the past 25 years.

While European

were substantially lower than those in the United

Europe today are substantially greater than current US

The unemployment rate in the United States has fluctuated

considerably, rising from 4.B to B.3 percent in the 1973-1975 recession then

declining to 5.B percent

to around 7.0 percent

inexorably since 1973.

today.

In

then rising to 9.7 percent in 19E2 before declining

1979,

in

In

contrast, unemployment in Europe has risen seemingly

France,

the unemployment rate has increased

in

every

single year since 1973, while it has declined only twice in Germany and the United

Kingdom.

The differences between the European countries and the United States are

most pronounced after

19B0.

While the US unemployment rate is at roughly its 1980

A

8

A

7

Table

1

European and U.S. Unemployment

1961-1986

United Kingdom

United States

France

West Germany

1961-1970

A.

1.9

.9

.8

1971-1975

6.1

2.8

2.6

1.8

1976-1980

6.7

5.2

5.3

3.7

1980

7.1

6.0

6.

3.

1981

7.6

9.2

7.7

A.

1982

9.7

10.6

8.7

6.9

1983

9.6

11.6

8.8

8.

1984

7.5

11.8

9.9

8.4

1985

7.3

12.0

10.7

8.

1986*

7.2

11.7

10.9

8.0

Source

.

Annual Economic Review

Forecast.

,

Commission of the European Communities, 1986,

level,

the unemployment

The rapid decline

countries.

continuing increase

forecasts

rate has approximately doubled in the three European

in

in

US unemployment

unemployment

in

Europe.

after

The

lest

Longer run forecasts are very similar

expected change.

European Commission put unemployment for the EEC as

10.

BV.

in

a

the table

line of

unemployment by the European Commission for 1966

of

compared to

19B2 contraiti iharply with the

i

gives

they show little

i

baseline projections by the

whole at

10.4'/.

in

1990,

19B5.

Differences in unemployment rates actually understate the differences in the

performance

American and European labor markets over the past decade.

of

suffered the concomitants

of

Between 1975 and

Europe has

high unempl oyment--r educed labor force participation and

involuntarily reductions in hours-- to

States.

-

19B3,

a

much greater extent than has the United

the labor force participation rate of

men in the

United States remained constant, while the corresponding rate in DECD Europe declined

by six

percent.

Average annual

States between 1975 and

percent in England.

performances

of

19B5 employment

hours worked declined by 2.7 percent in the United

19E2 compared with declines of

Perhaps the most striking contrast

7.5 percent

of

in

France and 6.1

the labor market

Europe and the United States is the observation that between 1975 and

increased by 25 percent,

or

about 25 million jobs in the United

States while declining in absolute terms in Europe.

1.2.

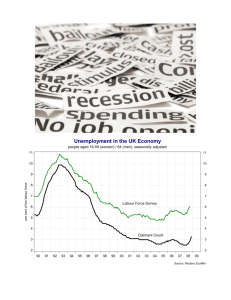

Unemployment Rates in the UK and the US over the last 100 veers

European unemployment has steadily increased and, pending an unexpected change

in

policy,

How unusual

is

is

expected to remain at this new higher level for the foreseable future.

such high and persistent unemployment?

now examine the behavior of

the US.

To answer

unemployment over the last 100 years

this question,

in

we

both the UK and

Figures

1

and

plot

2

unemployment

f

or

each

1B90-19B5 for the UK, and 1B92-19B5 for the US.

Estimation

UK

»

u

i

process

AR(1)

an

of

•for

)

+

e

j

cr.

*

2.1

.90 u(-l)

+

e

|

a.

«

2.0

u (-1

.93

of

the two countries,

for

the period

1

the whole

sample for each country gives

i

7.

(.04)

UB

=

u

:

'/.

(.04)

In

the degree of

both cases,

-first

order serial

Unemployment is indeed surprisingly persistent.

to return to

of

is

exhibits at best

high.

a

weak tendency

its mean.

Examination

evolution

It

correlation

the two figures --as well

of

the unemployment rate over

statistical

as

100 years is

the past

captured by any simple linear aut Dregr essi ve representation.

persistence as captured by the degree

of

wor k--suggests

1940,

it

it

In

The degree of

first order serial correlation reported

the UK,

around

when unemployment goes up from 1920 to

shows little tendency during that period to return to its pre 1920 level

then returns to

a

low level

during WWII,

current episode, both past and forecast,

after having sharply increased,

the

however not well

above arises in large part from relatively infrequent changes in the level

which unemployment fluctuates.

that

is

to stay there until

a

stabilizes at

the

1960's.

;

The

second instance in which unemployment,

a

new,

high level.

The US experienced

sustained increase in unemployment from 1929 to 1939, only to see unemployment drop

sharply during and after the war to

a

new,

much lower,

level.

persistence in unemployment is estimated separately for periods

average unemployment,

periods

of

there is some weak evidence

high average unemployment.

of

When the degree of

of

high and low

greater persistence within

a

cz

70

cz

CZ

ro

en

CD

CD

O

en

o

ro

C/l

LO

CD

O

o

P3

CD

ro

o

CD

o

CD

CD

O

CD

CD

O

s

.

The time series studied

the changes

in

They could be exogenous or

unemployment.

with

itself,

level

a

few years

unemployment,

of

level.

in

that

we

do not

which account

level,

the mean

isolation give little indication it to the cause

in

In

a

for

much of

the pertiitence

in

instead be triggered by unemployment

high unemployment triggering an increase in the mean

of

few years of

the absence of

a

low unemployment triggering

in

turn

a

decrease

tight specification of how this triggering occurs

believe that the data can easily distinguish between these two

possibilities

and we shall

not

attempt to do so at this stage.

Our finding that unemployment exhibits

a

very high degree of persistence over

century parallels the findings of Nelson and Plosser C19B23, Campbell

the past

of

Hankiw C19B6] and others that

a

other non-stationary processes.

variety

In

of

economic variables follow random walks or

many cases such findings can be easily

rationalized by recognizing that the level

of

technology is likely to be non-

stationary and that other variables like the level

But the failure of

and

unemployment to display more

of

output depend on productivity.

of

mean reverting tendency is

a

unlikely that non stationarity in productivity can account for the

troubling.

It

is

persistence

of

unemployment since the secular increase in productivity has not been

associated with any trend

3

3.

Pi

agnosi no Unempl

What sort

and

the

or

of

p

upwards drift in unemployment.

yment Pro bl em

theories can account for persistent high unemployment in general

current European experience in particular?

We

highlight the general

difficulties one encounters in explaining persistent unemployment by focusing on the

problem

of

explaining the current European situation.

its persistence.

The central

While it is easy to point to substantial,

puzzle it poses is

adverse supply and demand

4

e

shocks over the last

15

years, we argue that

our

standard theories do not easily

explain how they have had such enduring effects on the level

of

unemployment

3

.

Aooreoate demand

There is little question that Europe has been affected by large adverse demand

shocks,

especially since 19B0

(see

for

example Dornbusch

a

engaging in

a

major and prolonged fiscal

for the UK,

Germany and France

i

seal

.

19B3).

In

the

19B0's,

contraction

see Buiter

|

19B5 for

(see

Blanchard and Summers

more detailed study of

a

1

9 B

the UK

pol icy).

But to the extent that

natural

al

large extent matched tight US monetary policy while it the same time

Europe has to

f

et

aggregate demand shocks do not affect the equilibrium or

unemployment, one would expect sustained high unemployment to be

rate of

associated with rapid declines in the rate

inflation.

of

More generally,

standard

models of the effects of aggregate demand shocks would not predict that previous

estimates

of

the relationship between

There is substantial

there has been

a

unemployment

is

and

in

2

But

inflation than would have been predicted by

which gives the rates of

unemployment, there is no sign

experiencing

e

estimates

the rate of

of

in

the basic point that previous relations have broken down

19B5 for the United Kingdom,

small

unemployment would break down.

Below we examine the relation between wage inflation and

detail.

evidenced in Table

and

evidence however that this relation has broken down and that

much smaller decline

past relationships.

inflation

inflation and unemployment in 1964

France and Sermany.

of

Despite the high rates

of

disinflation, with the United Kingdom and Germany

increase in inflation and France

a

small

decrease.

Econometric

unemployment consistent with stable inflation show rapid

increases over the past decade.

Layard et

al

(

1

9B4

)

,

using crude time trends in

a

A

Table

2

Inflation and Unemployment in the U.K., France and Germany

1984-1985

United Kingdom

tt

France

U

71

Ge rmanv

U

IT

U

1984

A.

11.8

7.0

9.9

1 .9

8 .A

1985

5.5

12.0

5.7

10.7

2 ,1

8 .A

tt

=

U =

Rate of change of GDP deflator.

Unemployment

Source

.

Annual Economic Review, Commission of the European Communities, 1986.

Phillips curve relation, find the unemployment rate consistent with iteady inflation

to have

risen from 2.4

in

1967-70 to 9.2 in 19B1-19B3 in Britain, from 1.3 to 6.2

Germany and from 2.2 to 6.9 in France.

Coe

and

Gagliardi

framework of the Phillips curve but using instead

determinants

potential

of

explaining the increase

tine trend

a

also within the

a

battery

of

equilibrium unemployment as right hand side variables,

obtain roughly similar results.

in

of

(19B5),

in

Aggregate demand shocks have clearly played

European unemployment

in

|

they cannot

but

be

a

role

the whole

story given the increase in the rate of unemployment consistent with steady

i

nf

1

ati on.

Aooregate supply

Aggregate supply explanations appear more promising

increase in equilibrium unemployment.

the recent

research.

the goal

is

to

explain an

This is indeed the approach followed by much of

Sachs [1979,19B3D and Bruno and Sachs C19B5D have argued that

unemployment in Europe

shocks and real

if

is

in

large part the result of

wage rigidity.

The argument

is

a

combination

that real

of

adverse supply

wages do not adjust to

clear the labor market so that adverse supply shocks which reduce the demand for

labor at

a

given real wage create unemployment.

wage rigidity and the occurence

of

This argument has two parts,

real

adverse supply shocks. We start by reviewing the

evidence on the second.

Table

a

3

presents some information on the behavior

of

potential bearing on unemployment in the UK since I960".

various supply factors with

7

.

Table

3

Supply Factors and U.K. Unemployment

Year

Replacement

Rate (%)

Unemployment

Rate (%)

1960

2.3

42

1965

2.3

48

1970

3.1

1975

Mismatch

Index (%)

Productivity

Growth (%)

Change in

Tax Wedge (2)

1.9

.0

41

2.8

1.0

51

38

3.2

1.0

A.

49

43

2.7

.8

1976

6.0

50

38

1.5

2.8

1977

6.4

51

35

1.7

1.9

1978

6.1

50

35

1.4

-.9

1979

5.6

46

35

2.1

1.3

1980

6.9

45

37

1.5

1.3

1981

10.6

50

41

1.4

2.6

1982

12.8

54

37

1.1

1.0

1983

13.1

54

_

.5

-1.8

Notes

a) Standardized unemployment rate; source OECD.

b) Weighted average of replacement rates relevant to families of different sizes.

Source: Layard and Nickell (1985).

Index constructed as Z

u.-v.

where u. and v. are the proportions of unemplovment

i

i

and vacancies in occupation i respectively.

Source: Layard, Nickell and Jackman

(1984).

d) Rate of change of total factor productivity growth, derived by assuming" labor

augmenting technical change.

The first four numbers refer to the change in the

rate (at annual rate) over the previous five vears. Source: Layard and Nickell

(1985).

e) The tax wedge is the sum of the employment tax rate levied on employers and of

direct and indirect tax rates levied on employees.

The first four numbers refer

Source:

to the change in the rate (at annual rates) over the previous five years.

Layard and Nickell (1985).

c)

I

ii

I

10

first candidate is une mployme nt benefit

A

unemployment

if

Unemployment

s.

causes workers to search longer

it

less

or

reducing the pressure that unemployment puts on wages.

gives the average replacement ratio,

that

for

the average ratio of

is

!

little or no change in the replacement ratio.

since

1970.

shows an increase in real

Indeed,

Attempts to estimate the effect

unemployment have not been very successful

further discussion)

and one

is

shows no

it

wages,

higher unemployment but

of

roughly 30 1

a

in

eligibility rules rather than

the

(19E2)

and

Nickell

(1934)

for

increase in unemployment

large portion of the increase in

.

large scale reallocation of

increase unemployment.

increased the rate

labor

change

.

The argument

is

that the

associated with structural change tends to

Often it is suggested that the energy shocks of the

1970's

structural change and so led to higher unemployment.

The

adjustment to structural changes may be complicated by real wage rigidity.

The

of

fourth column of Table

and

role

another way of reading the

(see Minford

second candidate explanation is structural

Nickell

a

unemployment benefits on

of

led to conclude that

benefits probably does not account for

need for

|

Furthermore, it has been argued that the principle changes in

benefit levels.

A

3

after tax

workers

unemployment benefits

unemployment insurance have occurred through changes

unempl oyment

table

of

one can easily envision mechanisms through which

increases in unemployment benefits lead to higher real

it

of

column

This is not necessarily conclusive evidence against

over time.

unemployment benefits

column is that

intensively for jobs,

The second

unemployment benefits to earnings for different categories

clear movement

insurance may raise

Jackman

C

1

3

934

presents the index

D

.

The index

of

"mismatch" developed by Layard,

tries to represent the degree of structural

change in the economy by examining the extent to which unemployment and vacancies

occur

in

the same sectors.

The results in the table look at occupational

mismatch,

11

but

results are largely similar when industrial

There is little evidence

increase in the rate

an

of

and regional

measures are used =

structural

of

.

change since the

1960's when the unemployment rate was consistently low.

Perhaps the most common supply based explanations for persistent high

unemployment involve factors which reduce labor productivity and or drive

labor to firms and the wage workers receive.

between the cost

of

fifth columns of

the table

the change

the oil

30?.

reduction in the rate

of

total

Over the years the total

by

107.

since

wage consistent with full

it

.

had

in

1970.

of

wedge has also risen substantially,

by

tax

While it is still

of

a

factor productivity growth in the wake

true that the real

employment has risen fairly steadily,

the first half

and

factor productivity growth and

clear from the table that there has been

1960,

slowly than

The fourth

is

shocks.

since

wedge *

wedge

It

the tax

in

substantial

give time series for total

a

it

has

after-tax

increased more

the post war period.

The problem with aggregate supply explanations

now documented the presence of

We have

what might have been expected in the early

long lasting effect

If

and when

wages,

the

not

Dn

long run.

1970's.

But

unemployment.

to have

a

Individual

supply shocks are then reflected in real

labor supply is surely largely inelastic in

with aggregate demand explanations,

As

for these shocks

unemployment, there must be long lasting real wage rigidity.

labor supply becomes inelastic,

in

adverse supply developments relative to

we

face the problem of

explaining the mechanism that causes shocks to have long lived effects.

Recent models of union behavior

this problem by showing that

firms,

if

the result may be real

There is however

a

fundamental

(notably McDonald Solow 19B1) have addressed

wages are the result of bargaining between unions and

wage rigidity, with shocks affecting employment only.

difficulty with this line

of

argument.

To take the

f

12

developed by McDonald and Solow,

model

determined by the interaction

of

if

real

wages were truly rigid at

union preferences and firms'

rate

a

production technology,

employment would steadily increase and unemployment steadily decrease through time.

Annual

productivity improvements due to technical change are equivalent to favorable

supply shocks.

As

long as productivity increments and capital

accuulation led to the

demand curve for labor shifting outwards faster than the population grew,

unemployment would decline.

the cumulative

impact of

This appears count er actual

7

.

Even over the last decade,

productivity growth has almost certainly more than

counterbalanced the adverse supply shocks that occurred.

To rescue

this line of

thought,

it

must be argued that real

along some "norm", which may increase over time.

first is that the dynamic effects

way the norm adjusts to actual

and more

as

of

this has two implications.

The

supply shocks on employment then depend on the

productivity and this

left unexplained.

is

The second

important one here is that adverse supply shocks have an effect only as long

the norm has not adjusted to actual

catches up with actual productivity,

permanently.

can all

But

wages are rigid

be

It

productivity.

Thus,

unless the norm never

adverse supply shocks cannot affect unemployment

seems implausible that the current persistence

attributed to lags in learning about productivity.

of

high unemployment

Both the United

Kingdom and the United States have experienced enormous productivity gains without

evident reduction in unemployment over the last .century.

cannot be blamed simply on poor productivity performance.

to

surprises

in

productivity performance.

But

then

it

protracted unemployment from lower productivity growth.

is

High unemployment therefore

It

hard

can only be attributed

to see

how to explain

13

Where does this leave us

adverse shocks, be

in

it

lower

the tax wedge

of

oil

or

in

the

19B0's.

in

have argued that there is plenty of

than expected productivity growth,

in

the

differently,

Put

that

it

is

increases in the price

a

sustained effect on

difficult to account for the apparent increase

unemployment --or equivalently

the equilibrium rate of

of

standard theories do not provide us with

how these shocks can have such

of

evidence

1970's or contractionary aggregate demand policies

But we have also argued

convincing explanations

unemployment.

We

?

in

the unemployment rate

consistent with stable inflation-- by pointing to these shocks.

Borrowing from the

business cycle terminology,

of

I

it

is

not

difficult to find evidence

the difficulty is in explaining the propagation mechanism.

for mechanisms that can explain the propagation of

over

long periods of

time.

negative impulses

This leads us to look

adverse supply or demand shocks

These include the possibility that current unemployment

depends directly and strongly on past unempl oyment e

.

We

now consider various channels

through which this may happen.

1.4. Theories

Three types

"physical

of

of

capital",

Hysteresis

explanation which loosely speaking might be referred to as the

"human capital", and

"insider-outsider' stories can be adduced to

explain why shocks which cause unemployment in

a

single period might have long term

effects.

The physical

capital

story simply holds that reductions in the capital

stock

associated with the reduced employment that accompanies adverse shocks reduce the

subsequent demand for labor and so cause protracted unemployment.

frequently made in the current European context where

the very substantial

it

is

This argument

is

emphasized that, despite

increase in the unemployment rate that has occurred,

capacity

14

utilization

is

at

levels.

fairly normal

has shown no trend

over

with 76 percent in

1975,

the

B3

the EEC as

For

last decade.

stock

capacity utilization

whole,

currently stands at

It

percent in 1979,

argued that the existing capital

a

and 76 percent

in

percent compared

Bl

19B3.

It

is

then

simply inadequate to employ the current

is

labor <orce,

skeptical

are somewhat

We

of

the argument

account for high unemployment for two reasons.

possibilities for substitution

on

labor

it

is

First,

capital

for

stock affect the demand for labor

capital

above,

of

just

accumulation effects can

that capital

as

long

ex-post,

as

there are some

reductions

in

the

like adverse supply shocks.

As

unlikely that an anticipated supply shock would have an important effect

the unemployment

rate.

Second,

discuss

we

as

in

Section

A

below,

disinvestment during the 1930's did not preclude the rapid recovery

associated with rearmarment

substantial

noted

reduction

in

in

a

other countries.

number of

the civilian capital

the size of

substantial

of

employment

Nor did the very

stock that occurred during

many countries*.

the War prevent the attainment of

full

The argument that reduced capital

accumulation has an important effect on the level

of

employment after the War

unemployment is difficult to support with historical

A

in

examples.

second and perhaps more isportant mechanism works through "human capital"

broadly defined.

Persuasive statements

the potentially important effects of

of

unemployment on human capital accumulation and subsequent labor supply may be found

in

Phelps [19723 and Hargraves-Heap

be found

in

Clark and Summers

[ 1 ,9

B2

[

3

.

1

96

3

J

°

.

some suggestive empirical

Essentially,

the human capital

evidence may

argument holds

that workers who are unemployed lose the opportunity to maintain and update their'

skills by working.

r.ay

find

Particularly for the long term unemployed, the atrophy

of

skills

combine with disaffection from the labor force associated with the inability to

a

job,

to reduce the

effective supply of labor.

Early retirement may for

D

15

example be

middle aged workers to find new jobs.

unemployment environment,

signal

if

reasons employers prefer workers with long horizons,

capital

for

More generally,

semi-irreversible decision.

a

it

will

be

A

final

point

or

human

may be very difficult

it

that

in

high

a

difficult for reliable and able workers to

quality by holding jobs and being promoted.

their

is

incentive

for

inefficiencies in sorting workers may reduce the overall

The resulting

demand for labor.

Beyond the adverse effects on labor supply generated by high unemployment,

benefits

of

high pressure economy are foregone,

a

Clark and Summers

demonstrate that in the United States at least World War

in

raising female labor force participation.

labor force participation of

all

II

had

a

C 1

9

the

B2

long lasting effect

Despite the baby boom,

in

1950 the

female cohorts that were old enough to have worked

during the War was significantly greater than would have been predicted on the basis

of

pre-War trends.

trends.

role of participation during the War is evidenced by

the participation of

the fact that

the War

The causal

was actually lower

very young women who could not have worked during

than would have been predicted on the basis of

Similarly, research by Ellwood

[ 1

leave some "permanent scars" on subsequent

9E

1 3

suggests that teenage unemployment may

labor market perf or

through which this may occur is family composition.

performance

of

noted

One channel

(fiance.

The superior

labor market

married men with children has been noted many times.

Great Depression on fertility rates,

earlier

both in the US and in Europe,

The effect

has

of

the

often been

.

Gauging the quantitative importance of human capital

hysteresis is very difficult.

suggest that

mechanisms generating

Some of the arguments, early retirement for example,

labor force participation should decline rather than that unemployment

should increase in the aftermath of adverse shocks.

Perhaps

a

inore

fundamental

problem is that to the extent that there is some irreversibility associated with

16

unemployment shoe

response to

becomes more difficult to explain why temporary shocks have

early retirement is forever, why should

temporary downturn

that they are sufficient

doubtful

i

a

If

mechanisms can explain some

capital

pers

it

,

large short run effects.

such

in

k s

?

Overall,

of

the protracted response to shocks,

while

it

seems

taken

be

it

likely that human

it

is

completely for the observed degree

to account

of

st

ence

A

third mechanism that can generate persistence and that we regard as the most

.

promising relies on the distinction between "insider" and "outsider" workers,

developed in

for

of

series

a

of

contributions by Lindbeck

and used in an

example)

by bargaining

To

take an extreme case,

their jobs, not insuring the employment of

the absence of

in

importantly:

walk;

suppose that all

wages are set

Insiders are concerned with maintaining

shocks, any level

outsiders.

of

This has two implications.

employment

insiders is self-

of

insiders just set the wage so as to remain employed.

sustaining;

[19B5D

between employed workers--the "insiders "--and firms, with outsiders

playing no role in the bargaining process.

First,

and Snower

important paper by Gregory C19B5] to explain the behavior

Australian economy.

the

(see Lindbeck

in

the presence of

shocks,

employment follows

after an adverse shock for example,

of

process akin to

which reduces employment,

their insider status and the new smaller group of

maintain this new lower level

a

Second and more

employment.

a

random

some workers lose

insiders sets the wage so as to

Employment and unemployment show no

tendency to return to their pre shock value, but are instead determined by the

history

that,

shocks.

of

if

This example is

wage bargaining is

a

extreme but nevertheless suggestive.

prevalent feature

interactions between employment and the size

substantial

in

detail

in

of

of

the

the group of

employment and unemployment persistence.

the next

section.

labor aarket,

It

suggests

the dynamic

insiders may generate

This is the argument we explore

17

2.

Theory

A

of

Unemployment Persistence

This section develops

theory

*

of

unemployment persistence bated on the

distinction between insiders and outsiders.

As

the example sketched at

previous section makes clear, the key assumption

such

of

relation between employment status and insider status.

assumption as an assumption about membershi

p

rules

a

theory is that

We can think

of

of

the

of

this

the

key

the rules which govern the

,

relation between employment status and membership in the group

possibility

the end of

of

insiders.

The

persistent fluctuations in employment arises because changes in

employment may change the group's membership and thereby alter its objective

function 1

J

.

the first

In

bargaining between

part of

a

this section,

group of

we

insiders and

develop

a

a

partial equilibrium model

representative firm and characterize

employment dynamics under alternative membership rules

rather than the more natural

(We

use the term "group"

"union" to avoid prejudging the issue of whether the

membership considerations we stress are important only in settings

unions are present).

of

The second part

of

wh-ere

formal

the section extends the analysis to

a

general

equilibrium setting and shows how both nominal and real shocks can have permanent

effects on unemployment.

issues

of

j

the first

is

In

the remaining part of

that of the endogeneity of

the section,

we

consider nainly two

membership rules. The second is that

whether our analysis is indeed relevant only or mostly in explicit union

setttings.

2.1.

A

Model

of

Membership Rules and Employment Dynamics.

is

focus on the

To

of

d yn *

rr i

effects

c

insiders, the "group" for short,

presenting

aembership rules on the decision

of

formalize the firm is entirely passive,

we

labor demand on which the group chooses

a

start by characterizing employment and wages in

model,

it

is

membership

initial

preferred outcome

its

one period model.

a

In

a

1

*-

is

We

.

period

one

given and membership rules are obviously irrelevant.

is

But

intermediate step, which will allow us to contrast our later results

useful

a

the group

of

ones which treat membership as exogenous.

with traditional

attempt at generality and use convenient functional

retain analytical

Throughout, we make no

forms and some approximations to

simplicity.

The One Period Model

The group has initial

membership

unless otherwise nentioned).

follows,

-

(2. 1)

n

«

where

n

is

cw +

logarithms,

n

(in

It

faces

a

labor demand function given by:

employment,

is

w

the real

wage and

[Ee-a,

e

is

before

it

knows the realisation of

e.

Given

a

Ee+a].

the degree of uncertainty associated with labor demand.

w

w

and

random technological

The coefficient

outsiders are hired,

probability

of

If

n

less than no,

is

being laid off

is

the realisation of

Before specifying the objective function

w

and

n

,

the probability of

insider is equal

to one

if

being employed

n>n

.

no-n insiders are

the same for all

For n<no,

.

of

a

shock,

captures

The group must decide on

firm then chooses labor according to the labor demand function.

n

variables in what

are all

e

with mean Ee, uniformly distributed between

wage

as

If

n

e,

the

exceeds no,

laid off.

a

n-

The

insiders.

the group,

can derive,

we

The probability of

we approximate the

for

given

being employed for an

probability

(which is

19

not

be

in

logarithm)

of

good as long is

probability

(2.2)

n

being employed for an insider by l-n +n.

it

too much smaller thin

not

being employed

p

of

p

*

1

*

1

-

(l/4*)(no

+

is

given by

cw - Ee +

even under the worst outcome

If

the'

of

initial

decreasing function

of

the

probability

for

no

+

cw

>

Ee

-

a

for

n

+

ch

<

Ee

-

a

e»Ee-a and thus n"-cw+Ee-a --

is

-probability is an increasing function

decreasing function

membership no, and

degree of uncertainty

being employed in bad times,

of

mat

i

will

on

Under these assumptions,

then the probability of employment is clearly equal

larger than no,

Otherwise,

— which

i

the

derivations are in the appendix)

(all

a) 2

r,o.

This appr ok

of

a

|

of

is

n

to one.

expected productivity Ee,

the wage w.

the larger

It

a,

i

is

also

a

a

the lower the

while the probability remains equal

to

one in good times.

The second step is to derive the choice of

utility function

of

w

The group maximises the utility function of the

the group.

representative group member, which we specify as

U

*

p

+

is

not the most

The first reason is that,

specification

i

bw

Utility is linear in the probability

specification

This requires specifying the

.

of

as

natural but

will

be

of

employment and the wage.

it

is

however attractive,

seen below,

it

implies,

This

for two reasons,

together with the

probabilities given above, that the group exhibits the stochastic

equivalent of inelastic labor supply

i

an

increase in Ee

increase in real wages and leaves the probability

argued in the previous section that this is

determination given the absence

of

a

of

is

entirely reflected in an

employment unchanged.

desirable feature

of

We

any model

have

of

major trends in unemployment rates over long

wage

)

20

Note however that our

periods of time*?.

labor supply is the opposite of

a

assumption

of

stochastically inelastic

that used by McDonald and Solow.

Where they postulate

wage so that the labor supply curve is perfectly elastic,

rigid real

perfectly inelastic labor supply.

The second reason

is

that

it

li

we

postulate

analytically

convenient.

Replacing

w*

by

p

(1/c) (-no

-

value from

its

Ee

+

a (2

+

(b/c

(2.2)

)

-1

and

solving for the optimal

wage

givesi

w

)

Replacing in labor demand gives

n

no

«=

-

a(2(b/c)-l)

Replacing w*

in

p-

2

*

1-a (b/c)

+

equation

(e-Ee)

(2.2)

and rearranging gives the optimal

membership.

Thus the wage depends negatively on initial

0,

1)

As

by definition

whether expected employment exceeds membership depends on the sign

thus on whether b/c

is

less than

1/2 or

not.

The lower b,

the firm.

workers set

Note,

a

depends neither on the initial

Until

membership,

now,

a

of

membership.

a

(

b / c

)

-

If

c,

b/c

is

the

less

being employed

wage.

Given the initial

This wage and the realisation of

determine employment. But when we go from this one period model to

be

2

membership nor on expected productivity**.

the analysis has been rather conventional!

insiders choose

there may well

(

E(e-Ee)

wage low enough to imply expected net hirings of outsiders by

mentioned above that the optimal probability

as

a

the higher

smaller the wage reduction required to increase expected employment.

1/2,

of

i

the sore importance

workers attach to employment protection as opposed to the wage|

than

probability

a

a

disturbance

dynamic one,

relation between employment this period and next period's

This relation will

depend on the form

how this affects employment dynamics.

of

membership rules.

We

now examine

)

21

first define member shi

We

indexed by

being

first

periods lose member shi

m

is

the case where

The second

changes.

We

.

various membership rules as

can think of

Those workers who have been working in the fir* for the last

m.

periods belong to the group,

than

rules

p

current employment.

is

The

is

m

p

4

Workers who have been laid off for more

insiders.

are

^i

become outsiders.

infinity,

to

equal

m

the case where m«l

There are two extreme casesi

that

so

the initial

the

membe r ship never

that membership always coincides with

so

extreme cases highlight the effects

of

alternative

membership rules so we consider them before turning to the more difficult

i

ntermedi ate case.

'

The case of

a

constant membership

Let us denote by

employment in period

each period,

probability

if

of

ni

n_«

i.

beginning

In

(m*

nf

period

of

the present

exceeds no,

i

case,

i

i

membership, and by

members work

all

t y

;

if

n

s

is

being employed is given for each member by

and that the workers'

n

4

membership is equal to

assume that the one period utility function of

bwi)

ni

a

less than

to 6.

n_o

forever.

n_o,

as

So,

the

(approximately)

worker is given,

discount factor is equal

realised

l-n_o + ni.

above,

by

Thus the utility of

(p

s

We

+

a

member as of time zero is given by!

tpi + bKi3 where 6 is less than one

i«0

Assume for the moment that the shocks affecting

Eo E 6 1

Uo

over time,

or

more precisely that

e

t

iid,

is

uniform on [-&,+*].

below to the case of serially correlated shocks).

previous section, the probability

of

given by

=

(using the fact that Ee

s

labor demand are uncorrected

i

shall

return

Then by the analysis of the

being employed in period

0)

(We

i,

conditional on

w

s

is

)

.

22

pi-1

=

1

forn_o+cwi>-a

-

(

1

/ 4

1

)

(

4

no

w,

c

+

a

2

for

)

Given that employment outcomes do not

assumption that shocks Art white noise,

n_ D

ch,

+

<

-a

iHtct future membership,

the problem faced by

and

given the

members is the same

every period, and thus its solution is the same as that derived abovei

(2.3)

In

W,

=

n,

=

(l/c)(-

n_o

a

(

n_o

2

(

a(2(b/c)-l)>

+

b/c

)

-

1

)

+

e

response to white noise shocks,

and

,

employment will

smaller

has

It

to hold

larger than 1/2.

choose

they will

•firm

or

a

is

cushion

on

average,

outsiders who are laid

employment exceeds membership and the

adverse shocks.

first

in

case

easy to see that the result that employment

is

white noise will

o-f

regardless

of

of

e

the properties of

-f

e

is

e.

As

or

continue

shown above,

stochastically inelastic.

Changes

our

in

the

wages but do not affect the level

of

employment.

from its expected value affects the level

of

employment.

affect real

Only the deviation of

o-f

the stochastic process followed by

assumptions insure that labor supply

expected value

(b/c)

the insiders want strong employment protection,

If

wage so that,

a

Whether

membership depends on whether

employment is on average larger or smaller than

is

also be white noise.

rational expectations,

the unexpected component of

serially uncorr el ated

The case where membership eouals eitDlovment

(

m*

1

e

must be

By

)

(

23

We

now go to the opposite extreme,

employment.

i-1

i

this case membership at time

In

rw-i.

n_i

applied it to

(2.3')

Thus,

which membership comet and goes with

in

n_i

If

group kept the same decision rule 11 in equation

the

rather than to

n,_,

n,

simply given by employment at time

is

i

-

equation

n_o,

a(2(b/c)-l)

employment would follow

+

with drift.

under the assumption that membership equals beginning

given by

not

(2.3').

Optimal

current members should

memberships to wage policies.

changes fundamentally the character of the maximization problem.

membership, when taking wage decisions today,

next

period by

a

membership which will

This implies in particular that

laid off

The group

be

different from that

did not affect his future chances of

being hired

1

simplifying assumptions we have made so far, the problem

today.

j

this

where being

is

Even with the

intractable unless we

further simplify by linearizing the group's intertemporal objective function.

be

taken

be

*.

solution to this problem is treated in the appendix.

The formal

of

keeping employment with the firm

lower wage than in the previous case,

a

This

knows that wage decisions will

general

in

thus considerably decreases his chances of

presumably leads him to choose

The

insider is laid off, he becomes an outsider and

an

if

wage behavior

depend on its then current membership.

the group will

of

i

period employment is however

of

(2.3')

Unlike the behavior implied by

recognize their inability to commit future

subsequent policies

but

e,

random walk,

a

would become

(2.3)

(2.3)

Let w'

the wage around which the objective function is linearized and let the shocks to

labor demand be white noise.

(2.4)

W»

-

(l/c)(-

nt

»

n,-i

=

n_i_,

a (2

The solution to the maximization problem is then

+

(b/c)

a(2(b/c>

(

1

/

(

1

+

(

bSw

The probability of employment for

i+b6w

1/

'

)

a

>

-1

)

+

'

)

>-l

:

>

e

nember is

a

constant and is given by

i

24

«

p*i

Thus,

For

a

1

-

at (b/c) (1/

(l+bGw

'

)

under this membership rule,

2

employment follows

i^tct current employment,

expected employment.

)

drift

The

is

In

such

a

case,

random walk with drift.

Uncorr

and through employment,

positive

if

(b/c)

workers care sufficiently about the probability

wage.

t

there is unemployment hysteresis.

given labor •force,

labor demand

)

of

is

e

1

a t

shocks to

ed

membership and future

less than

(

1

+b©

w

'

)

/ 2

employment as compared to the

although they do not care about the unemployed, they will

the wage each period so as to have the firm hire on average new employees.

the wage

given membership,

the probability of

if

,

is

always set lower than

employment is set higher;

loss of membership and imposes

a

in

For

the m«infinity case

set

a

and thus

this is because being laid off

implies

a

much larger cost than before.

This analysis can again easily be extended to the case where labor demand shocks

The results remain the same;

are serially correlated.

a

random walk.

This is

a

consequence

of

our

maintained assumption that expected

changes in labor demand have no effect on the level

The

Intermediate Case

(m

between

1

and

employment continues to follow

of

employment.

infinity)

The intermediate case where workers remain insiders for some time after

losing

their jobs and where newly hired workers eventually but not immediately become

insiders raises an additional conceptual problem.

among insiders.

There will

no

longer be unanimity

Those who have already experienced some unempl oyaent

have been working in the firm for

a

short period of time,

cautious wage setting policies than those who have not.

face of conflict between members is beyond our grasp**,

for

A

A

,

or

those who

example will favor more

theory

of

behavior

plausible conjecture

in

is

the

25

that allowing for

values

of

to

1

case but

me »

less cautious than in the

More

between

m

• leads

and

to wage

setting policies that trt

importantly, rules corresponding to

m

unexpected shocks

employment.

In

the

of

lose insider status

|

in

level

of

namely

and 2,

1

Short sequences

unemployment.

of

sign have little effect on membership and thus on mean

same

the case of

the

in

case.

between one and infinity are likely

generate unemployment behavior such that shown in figures

infrequent but sustained changes

!

more cautious than in the

adverse shocks,

the case of

enough, to acquire membership.

But

insiders are not laid off

long enough to

favorable shocks, outsiders do not stay long

long --and

infrequent-- sequences

of

shocks

of

the

same sign have large effect on membership and may lead to large effects on the mean

level

of

employment. The length

employment depends

on

the

of

the shock necessary to cause

membership rules.

rules have to be symmetric.

The length of

general

permanent change

in

there is no reason why these

time after which an unemployed worker

becomes an outsider need not equal the length

insider.

In

a

of

time until

a

new worker becomes an

Hence favorable and unfavorable shocks may persist to differing extents.

The results of this section have been derived under very specific assumptions,

from fixed membership rules to the assumption that the firm was passive and that

outsiders played no role, direct or indirect,

return to these assumptions.

in

the negotiation process.

We

must

Before we do so however, we first show how the model of

this section can be used to generate permanent effects on aggregate employment of

both nominal

and real

shocks.

2.2 Persistent Effects of

Nominal

and Real

Disturbances on Unemployment.

26

We

now assume that there ire many firms in the economy,

insider workers.

own group of

so

that nominal

of

nominal

many firms

imperfect substitute for all

facing firm

is

j

gi ven

-k (p j-p)

yj

then characterize the effects

We

+

by

(m-p)

indexed by

others,

but

simplicity.

j

,

m

product which

being otherwise identical.

The demand

and pj

and

p

constants are ignored for notational

denote the output and the nominal

The restriction on

is

k

price charged

denote nominal money and the price level.

the firm's output depends on the relative price

balances.

a

k>l

The variables yj

respectively,

each selling

j,

i

variables are in logarithms and all

All

by firm

terms,

disturbances on employment and real wages.

The economy is composed of

an

nominal

in

its

derived demand for labor facing each group

The

is

further assume that wages trt set

disturbances can affect employment.

real

and

We

each dealing with

as

well

as

on

Demand for

aggregate real

money

needed to obtain an interior maximum for profit

maximisation.

Each firm operates under constant returns to scale

and employment

is

given by yj

«

nj.

If

Wj

constant returns and constant elasticity

are

given by

common to all

pj

Wj

firms

1

-

*.

e,

where

e

is

a

is

of

the

;

the relation between output

wage that firm

the demand

for goods

j

pays its workers,

imply that prices

random technological shock, which is assumed

i

27

Each

•firm

which chooses

faces

j

relation between

the demand

(2.5)

f

and wj,

pj

iniidert with the tame objective function at above,

of

wage and lets the firm determine employment.

nominal

a

group

t

can think of

we

each group

j

as

Given the

choosing wj subject to

unct on

i

nj

-

k(wj-e-p)

The choice of

(m-p)

+

and employment

the wage

decisions

We now characterize the

each group

j

at

time zero

moment we do not introduce the time index explicitly).

We

assume each group to

of

operate under the membership rule m«l,

given by nj(-l).

The group now chooses

its expectations of

the technological

shown earlier,

the price

shock,

Ee,

given such

a

level,

+

assumption

all

i

of

,

rational

we

level,

«

n(-l).

so that

real

wage,

of

employment

(Em -

Ep)

and the expected value of

to its

this implies

function

of

it

As

we

have

chooses

membership plus

a

a

!

nj(-l), Em,

must solve for the value of Ep.

expectations.

is

nj(-l)

«

a

equal

is

j

based on

enter the derived demand for labor.

As

all

We

Ep

and Ee.

do so under

the

firms and groups are the same,

affected by the same aggregate nominal shock, all

nj(-l)

a

demand function and its objective function,

which defines implicitly wj as

To solve for Wj

aembership in group

time zero,

nominal money, Em,

Ep,

Ignoring again the constant,

k(wj-Ee-Ep)

(2.6)

at

nominal rather than

a

which all

wage so that the expected level

constant term,

so that

(and for the

and are

groups have the same membership

Furthermore all nominal prices are the same and equal to the price

the first term in

(2.6)

is

equal

to zero.

Thus,

from

(2.6)

2B

Ep

w

*

j

Em

-

n(-l)

Ee

+

Em

and

n(-l)

-

depends on expected nominal

The expected price level

the

wage

The nominal

membership.

expected technological

values in

by their

dynamic behavior

or,

if

(2.7)

of

shock,

and

and

negatively

aggregating over

(m-Em)

+

=

ni-j

+

Replacing Wj and Ep

membership.

gives the equation characterizing

j

the

(e-Ee)

+

(mi-Em,)

on

money and

i

reintroduce the time index

we

hi

turn depends positively on expected nominal

in

aggregate employment

n(-l)

*

n

(2.5)

money and negatively on

+

i,

(e,-Ee,)

Shocks, employment and wages.

From

(2.7)

only unexpected shocks affect employment.

In

the case

of

real

shocks,

inelastic labor supply, which imply that

this comes as before -from the assumption of

each group sets wages so as to leave employment unaffected by anticipated real

shocks.

In

the case of

contract aodels

nominal

level

(Fischer

wage which,

employment.

of

nominal

in

1977)

shocks,

the

and the

intuition is straightforward.

result

is

the same

view of expected aggregate demand,

as

will

in

other nominal

Workers set

a

maintain last period's

Firms simply mark up over this nominal wage.

Unexpectedly low

aggregate demand leads to unexpected decreases in output and employment, with no

changes in nominal wages

returns

l

)

(by

assumption)

and

prices

in

(because of constant

*.

These unexpected nominal

and real

shocks,

however permanent effects on employment.

membership rules.

unlike other contract nodels, have

This is the result of our assumptions about

Once employment has decreased,

it

remains,

in

the absence

of

other

29

shocks, permanently *t the lower

level.

sequence

A

of

unexpected contractions in

aggregate demand increases equilibrium unemployment permanently.

m,

the membership

was

rule,

greater than one,

While the implications for employment

would again obtain the result that

are straightforward,

there is no simple relation between employment and real

particular the effects of nominal shocks.

scale and constant elasticity of demand,

Equi val ent

This lack of

assumptions

of

1

y

,

the role of

assumption

the model

wages.

of

implies

Consider in

constant returns to

they leave the mark up of prices over wages

wage unaffected.

Thus,

a

sequence

of

a

simple relation between real

wages and employment comes from our

monopolistic competition and constant returns, not from our

membership rules,

But

By our

they leave the real

assumptions about insiders and outsiders.

further.

it

we

is

real

an

do not

As

our

focus is on the dynamic effects of

explore the relation between real

wages and employment

important caveat to the line of research which has focused on

wages in "explaining" high European unemployment.

In

the model

constructed here,

it

is

quite possible to have sustained high unemployment without

high real

It

is

also possible for expansionary policies to raise ecployment

wages.

without altering real

2.3.

a

disturbances will decrease employment, with no effect on the real

adverse nominal

wage.

assumed that

such shocks would increase equilibrium unemployment permanently.

long sequence of

unaffected.

we

adverse shocks had no effect on equilibrium unemployment,