m 1 Jl I

advertisement

MIT LIBRARIES

3 9080 02617 8381

Jl

I

;

II

'

I

Warns sifflljfflj

Wm

m

8flHftIft

I Hi

BUS

1 Hi

9

'';i;i.'!

:

'i

';!;.

I

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

Boston Library Consortium

Member

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/fiscaldominanceiOOblan

3

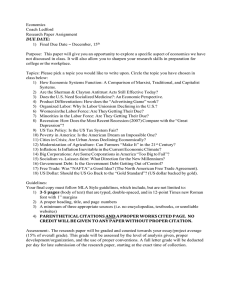

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Economics

Working Paper Series

Fiscal

Dominance and

Inflation Targeting.

Lessons from

Brazil

Olivier Blanchard

Working Paper 04-1

March 15,2004

Room

E52-251

50 Memorial Drive

Cambridge,

MA 02142

paper can be downloaded without charge from the

Social Science Research Network Paper Collection at

This

http://ssrn.com/abstract=51 8265

SSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

APR

1

h 2004

LIBRARIES

Fiscal

Dominance and

Inflation Targeting.

Lessons from Brazil.

Olivier Blanchard.*

March

*

15,

2004

MIT and NBER; Visiting Scholar, Russell Sage Foundation. I thank Eliana Cardoso, Francesco

and Santiago Herrera for many useful discussions. I

thank Ricardo Caballero, Arrninio Fraga, Marcio Garcia, and Eduardo Loyo for comments.

The paper has also benefited from discussions with staff members at the Central Bank, and the

Ministry of Finance of Brazil. The data and programs used in the paper are available on my web

Giavazzi, Ilan Goldfajn, Charles Wyplosz,

also

site.

Brazil

Abstract

A

standard proposition in open-economy macroeconomics

is

that a central-bank-

engineered increase in the real interest rate makes domestic government debt more

attractive

and leads to a

real appreciation.

If,

however, the increase in the real

interest rate also increases the probability of default

be instead to make domestic government debt

depreciation.

That outcome

is

more

on the debt, the

less attractive,

effect

and to lead to a

may

real

likely the higher the initial level of debt, the

higher the proportion of foreign-currency-denominated debt, and the higher the

price of risk.

Under that outcome,

inflation targeting

can clearly have perverse

effects:

An

in-

crease in the real interest in response to higher inflation leads to a real depreciation.

The

real depreciation leads in turn to a further increase in inflation. In this case,

fiscal policy,

not monetary policy,

This paper argues that this

in

2002 and 2003.

It

is

is

the right instrument to decrease inflation.

the situation the Brazilian economy found

itself in

presents a model of the interaction between the interest rate,

the exchange rate, and the probability of default, in a high-debt high-risk-aversion

economy such

as Brazil during that period. It then estimates the model, using

Brazilian data. It concludes that, in 2002, the level and the composition of public

debt in Brazil, and the general level of risk aversion in world financial markets,

were indeed such as to imply perverse

rate

and on

inflation.

effects of

the interest rate on the exchange

Brazil

A

standard proposition in open-economy macroeconomics

is

that a central-bank-

engineered increase in the real interest rate makes domestic government debt more

and leads to a

attractive

real appreciation.

If,

however, the increase in the real

interest rate also increases the probability of default

be instead to make domestic government debt

depreciation.

That outcome

is

more

on the debt, the

less attractive,

effect

and to lead to a

may

real

likely the higher the initial level of debt, the

higher the proportion of foreign-currency-denominated debt, and the higher the

price of risk.

Under that outcome,

inflation targeting

can clearly have perverse

effects:

An

in-

crease in the real interest in response to higher inflation leads to a real depreciation.

The

real depreciation leads in turn to a further increase in inflation. In this case,

fiscal policy,

not monetary policy,

This paper argues that this

in

is

is

the right instrument to decrease inflation.

the situation the Brazilian economy found

itself in

2002 and 2003.

In 2002, the increasing probability that the left-wing candidate, Luiz Inacio Lula

Silva,

would be

of interest

reflecting

the debt.

The

elected, led to

an acute macroeconomic

crisis in Brazil.

The

da

rate

on Brazilian government dollar-denominated debt increased sharply,

an increase in the market's assessment of the probability of default on

The

Brazilian currency, the Real, depreciated sharply against the dollar.

depreciation led in turn to an increase in inflation.

In October 2002, Lula was indeed elected. Over the following months, his commit-

ment to a high target

for the

primary surplus, together with the announcement

of a reform of the retirement system, convinced financial markets that the fiscal

outlook was better than they had feared. This in turn led to a decrease in the

perceived probability of default, an appreciation of the Real, and a decrease in

inflation. In

many

ways, 2003 looked

like

2002 in reverse.

While the immediate danger has passed, there are general lessons to be learned.

One

of them has to do with the conduct of monetary policy in such an environment.

Brazil

Despite

its

commitment

to inflation targeting, and an increase in inflation from

mid-2002 on, the Brazilian Central Bank did not increase the real interest rate

beginning of 2003. Should

until the

it

it

have? The answer given in the paper

is

that

should not have. In such an environment, the increase in real interest rates would

probably have been perverse, leading to an increase in the probability of default,

to further depreciation,

decrease inflation was

and to an increase

fiscal policy,

and

in inflation.

in the end, this

The

is

right instrument to

the instrument which

was used.

The theme

the

modern

Woodford's

of fiscal

dominance of monetary policy

literature

from Sargent and Wallace

by Loyo

specific incarnation, to

monetary policy

tions for

an old theme, running

[1999].)

show

its

in general,

The

contribution of this paper

empirical relevance, and to draw

and

in

[1981] "unpleasant arithmetic" to

theory of the price level" [2003] (with an application of

"fiscal

ford's theory to Brazil

on a

is

Wood-

is

to focus

its

implica-

for inflation targeting in particular.

The

paper has two sections:

Section

1

formalizes the interaction between the interest rate, the exchange rate,

and the probability of

default, in

a high-debt, high-risk-aversion economy such as

Brazil in 2002-2003.

Section 2 estimates the model using Brazilian data.

level

It

concludes that, in 2002, the

and the composition of Brazilian debt, together with the general

level of risk

aversion in world financial markets, were indeed such as to imply perverse effects

of the interest rate

1

A

on the exchange rate and on

inflation.

simple model

In standard open

economy models, a central-bank-engineered increase

interest rate leads to

a decrease in inflation through two channels.

in the real

First, the higher

demand, output, and

in turn, inflation. Sec-

ond, the higher real interest rate leads to a real appreciation.

The appreciation then

real interest rate decreases aggregate

Brazil

decreases inflation, both directly, and indirectly through the induced decrease in

demand and

aggregate

The

output.

question raised by the experience of Brazil in 2002 and 2003

of the second channel. It

is

is

about the sign

whether and when, once one takes into account the

effects of the real interest rate

on the probability of default on government debt, an

increase in the real interest rate

may

lead, instead, to

a real depreciation. This

The

the question taken up in this model, and in the empirical work which follows.

answer

is

what we need to know to

clearly only part of

monetary

policy,

but

it is

a crucial part of

the findings for overall monetary policy

The model

•

A

is

it.

is left

A

assess the overall effects of

discussion of the implications of

to the conclusion of the paper.

a one-period model. The economy has (at least) three financial assets:

one-period bond, free of default

Inflation,

tt,

will

to distinguish

risk,

with nominal rate of return

be known with certainty

in the

between expected and actual

return r on the

bond

(in

model

inflation,

terms of Brazilian goods)

1

1

I

is

is

so there

and the

i.

no need

is

real rate of

given by:

+i

+ 7T

shall think of r as the rate controlled

by the central bank (the model

equivalent of the Selic in Brazil).

•

A

one-period government bond denominated in domestic currency (Reals),

with stated nominal rate of return in Reals of i R

.

R

Conditional on no default, the real rate of return on this bond, r

,

is

given

by:

1

+ 7T

Let p be the probability of default on government debt (default

to be

full,

is

assumed

leading to the loss of principal and interest). Taking into account

Brazil

the probability of default, the expected real rate of return on this

bond

is

given by:

(l-p){l

A

•

+ r*)

one-period government bond denominated in foreign currency (dollars),

with stated nominal rate of return in dollars of

i

$

.

Conditional on no default, the real rate of return (in terms of U.S. goods)

on

this

bond, r $

,

is

given by:

where stars denote foreign variables, so

it* is

foreign (U.S.) inflation.

Conditional on no default, the gross real rate of return in terms of Brazilian

goods

given by:

is

7(1

where

e

+ r$

)

denotes the real exchange rate, and primes denote next-period vari-

ables.

Taking into account the probability of default, the gross expected

of return

on

this

bond

is

given by:

(l-p)i(l+r $

a

)

Equilibrium rates of return

1.1

We

real rate

need a theory

full

for the

determination of r R and r $ given

r. I

shall stay short of

characterization of portfolio choices by domestic and foreign residents, and

simply assume that both risky assets carry a risk premium over the riskless rate,

7

Brazil

so their expected return

is

given by:

(l-p)(l

+r

=

fl

)

(l

+

r)

+ 0p

(1)

and

f

(l-p)-(l +

Both

assets are subject to the

The parameter

same

r

=

$

)

risk,

(l

+ r) + 0p

and so carry the same

for the variance of the return.

p proxies

relevant, values of p, the variance

is

roughly linear in

algebra below.

1

Note the two

roles of the probability of default in

on government debt.

First,

a higher stated rate

expected rate of return; this

equations. Second,

if

premium.

is

is

p,

The

For empirically

and using p

simplifies the

determining the stated rate

required to deliver the same

captured by the term

(1

— p)

on the

left in

both

investors are risk averse, a higher expected rate of return

required to compensate

1.2

risk

6 reflects the average degree of risk aversion in the market.

probability of default

right in

(2)

them

for the risk; this is

is

captured by the term 6p on the

both equations.

Capital flows and trade balance

The next

step

is

to determine the effect of the probability of default, p,

real interest rate, r,

on the

real

exchange

rate,

e.

To do

and

of the

so requires looking at the

determinants of capital flows.

Let the nominal interest rate on U.S. bonds be

of return (in terms of U.S. goods)

Assume

1.

on these bonds

foreign investors are risk averse,

and U.S. government

The variance

the variance

is

is

so the gross expected real rate

is

(1

+ r*) =

(1

+ i*)/(l + tt*).

and choose between Brazilian

dollar

bonds

dollar bonds, so capital flows are given by:

V = p(l -p)(l + r R So, using equation (1) with pV replacing p9,

2

by V(l — p) = p((l + r) + QV) and depends on p, r and 0. For

say p less than 0.2, V « p.

given by

implicitly defined

small values of p however,

i*,

)

.

,

Brazil

CF = C

The

first

bonds

reflects

(-(l-p){l +

r

C>

e

- -{\ + r*) -

$

)

9*p\

two terms are the expected rates of return on Brazilian and U.S. dollar

respectively,

both expressed in terms of Brazilian goods. The third term

the adjustment for risk on Brazilian dollar bonds:

The parameter

9* reflects

the risk aversion of foreign investors, and p proxies, as before, for the variance of

The higher the expected return on

the return on Brazilian dollar bonds.

Brazilian

on U.S. dollar bonds, or the lower

dollar bonds, or the lower the expected return

the risk on Brazilian bonds, the larger the capital inflows.

Using the arbitrage equation between

bonds derived

earlier,

risk-free

domestic bonds and domestic dollar

the expression for capital flows can be rewritten

as:

CF = C f(l + r) - 1(1 + r*) + (9 - 9*)p)

Whether an increase

depends therefore on

in the probability of default leads to a decrease in capital flows

(9

— 9*),

the difference between average risk aversion and the

risk aversion of foreign investors. If the

two were the same, then the increased

probability of default would be reflected in the equilibrium rate of return, and

foreign investors

would have no reason to reduce

appears to be however the case where 9*

risk aversion

>

9,

simple

way

of capturing this

is

relevant case

where foreign investors have higher

the assumption

assume that 9 and

=

X9*,

the foreign investors' risk aversion.

Whether sharp changes

is

to

so the the average risk aversion in the

2.

The

than the market, so an increase in risk leads both to an increase

the stated rate and to capital outflows. This

A

their holdings.

2

A

<

make

here.

9* satisfy:

1

market increases

(3)

less

Under that assumption,

in capital flows (the so called

I shall

in

than one

for

one with

capital flows are given

"sudden stops") actually

reflect

changes

Brazil

by:

CF = C

((1

+ r) - ^(1 + r*) -

(1

-

\)6*p\

Turn now to net exports. Assume net exports to be a function of the

real

exchange

rate:

NX = N(e)

N' >

Then, the equilibrium condition that the sum of capital flows and net exports be

equal to zero gives:

C ((I + r) In a dynamic model,

e'

e

-(l

+ r*) -

-

(1

X)9*p\

+ N(e) =

would be endogenously determined. In

model, a simple way to proceed

is

this one-period

as follows. Normalize the long run equilibrium

exchange rate (equivalently the pre-shock exchange rate) to be equal to one. Then

assume:

e'

with

rate

r\

between zero and one. The

=

closer

moves with the current exchange

r\

e"

is

rate,

to one, the

more the future exchange

and by implication the

larger the real

depreciation needed to achieve a given increase in capital flows.

Replacing

e'

in the previous equation gives us the first of the

two relations between

on the part of foreign investors, or other factors (factors generally referred to as

not important here (for an approach based on liquidity shocks, see for example

in risk aversion

"liquidity")

is

Caballero and Krishnamurthy [2002].) All these can be captured by changes in 9". What is

important is that these shifts affect foreign investors more than the average investor in the market.

_10

Brazil

e

and p we

need below:

shall

C ((1 + r) - e"-

This

first

1

(1

+ r*) -

(1

-

relation between the exchange rate

plotted in Figure

+ N(e) =

A)0*p)

(4)

and the probability of default

is

1.

An increase in the

probability of default increases risk. This increase in risk leads to

an increase

exchange rate

The

in the

—to a depreciation: The locus

is

upward-sloping. 3

slope depends in particular on the degree of risk aversion, 0*.

drawn

in the figure:

The

flatter

one corresponds to low

Two

loci are

risk aversion; the steeper

one corresponds to high risk aversion.

For a given probability of default, an increase in the interest rate leads to a decrease

exchange

in the

rate, to

monetary policy

—the

the exchange rate.

standard channel through which

To a

effects of

[Figure

1.

an increase

in the interest rate

The exchange

step

interest rate, r,

is

The two dotted

on the equilibrium

lines

show the

locus.

rate as a function of the probability of default.]

Debt dynamics and default

The next

approximation, the vertical

first

the locus does not depend on risk aversion.

shift in

1.3

affects

an appreciation

risk

to determine the effect of the real exchange rate,

back on the probability of default,

p.

e,

and the

This requires us to look

at

debt dynamics.

Assume the government

finances itself by issuing the two types of

bonds we have

described earlier, some in Real, some in dollars, both subject to default

If C(.) and N(.) are linear, then the locus

do not depend on convexity.

3.

is

convex.

I

draw

it

risk.

as convex, but the results below

High

risk

aversion

risk

Figure

1

.

Exchange

rate

aversion

as a function of default

risk

—

U

Brazil

D

Denote by

s

the amount of dollar-denominated debt (measured in U.S. goods)

Given the current

at the start of the period.

real value (in Brazilian

real

goods) of this dollar debt

is

exchange rate

e,

the current

D^e. Absent default, the real

value (again, in Brazilian goods) of the dollar debt at the start of next-period

(D

$

(l

+r

$

is

)e').

Denote by

DR

the

amount

of Real-denominated debt (measured in Brazilian

goods) at the start of the period. Then, absent default, the real value of this

Real-denominated debt at the start of next period

is

D R (l + r R

Conditional on no-default, debt at the start of next period

D'

where

X

is

is

).

thus given by:

= D $ (l + r $ )e' + D R (1 + r R )-X

the primary surplus.

Using equations

(1)

and

(2) to eliminate (1

+ r$

)

and

(1

+ rR

and equation

),

(3)

to replace 6 by \9*, gives:

D'

=

(-

l—p

+

-

1

— £)

p

D $ e + D R -X

L

For convenience (so we can discuss composition versus level effects of the debt),

define

\i

as the proportion of dollar debt in total debt at the equilibrium long-

run exchange rate (normalized earlier to be equal to one), so

fi

= D^/D,

where

D

= (D + D R ). The above equation becomes:

A

higher probability of default affects next-period debt through two channels:

$

leads to a higher stated rate of return

rate of return; this effect

is

It

on debt so as to maintain the same expected

captured through 1/(1

—

p).

And,

if

risk aversion

is

.

12

Brazil

positive, the higher risk leads to a higher required expected rate of return; this

effect is

The

If

captured through \9*p.

last step is to relate the probability of default to the level of

we think

of the probability of default as the probability that debt exceeds

(stochastic) threshold, then

we can

p

=

zone,

flat for

and then

Putting the

flat

last

ip{.)

i\)'

>

as a cumulative probability distribution, low

low values of debt, increasing rapidly as debt enters a

two equations together gives us the second relation between the

\

Note that p depends on

itself in

with p on the horizontal

axis,

we

shall

need below:

(5)

1— p

1— p

J

a complicated, non linear fashion. To explore this

relation, Figure 2 plots the right-

and the left-hand

and both p and

sides of the previous equation,

ip(.)

on the

values of the other variables, including the exchange rate.

is

given by the 45 degree

line.

•

2.

If it

The

has

For any

vertical axis, for given

The

The shape

depends on whether the underlying distribution has

[Figure

critical

again and close to one as debt becomes very high.

probability of default and the exchange rate

a function of p,

some

write:

ip{D')

and we can think of the function

and nearly

debt next period.

of

left

tp

as

hand

side, p, as

a function of p

infinite or finite support.

probability of default as a function of itself]

infinite support,

then the shape of

tp is

as

shown by the locus AA"

level of debt, there is a positive probability of default,

small. Thus, even for

p

—

0, ip is positive.

As p

however

increases, so does D',

and

p,

^

A

Figure 2. p and

W

as functions of p

.

Brazil

13

so does

As p tends

ip.

to one, 1/(1

— p)

tends to

infinity, so

does D', and

ip

tends to one.

•

If it

has

finite

support, then the shape of ip

In this case, there

a

is

probability of default

critical value of

is

zero.

shown by the locus OA'A"

as

is

next-period debt below which the

So long as

the interest rate, and

initial debt,

the primary surplus are such that next-period debt remains below this

ical value, increases in

some value

as

p tends

p do not

increase

ip,

of p, the probability of default

to one,

ip

which remains equal to

becomes

enough, there

and O,

C and A"

may be no

p

=

C and A"

is

uninteresting.

I

shall

Standard comparative

assume

statics

in

what

high

=

arguments eliminate the

1 is

present in any model

the lower equilibrium (O or B) and that such an equilibrium exists. Under this

there

but

If

is

follows that the relevant equilibrium

assumption, we can draw the relation between p and

If

in the case of

leave this standard case of

1; I

middle equilibrium (C or C). The equilibrium with p

is

And, as before,

in the case of finite support.) (If debt

equilibrium except

credit rationing aside here.)

and

For

tends to one.

This implies that there are typically three equilibria (B,

infinite support,

positive.

0.

crit-

is

is

no dollar debt

(/x

=

0),

then the locus

is

e

implied by equation

horizontal:

p may be

(5).

positive

independent of the exchange rate.

there

is

dollar debt, then the locus

the exchange rate

or upward-sloping

becomes

is

is

either flat

(if

the support

such that next-period debt remains below the

(if

positive.) If

the exchange rate

it is

upward-sloping,

is

its

is finite,

and

critical level),

such that the probability of default

slope

is

an increasing function of the

proportion of dollar debt, and an increasing function of total

initial debt.

Figure

3 shows two loci, one with a flat segment, corresponding to low initial debt, the

other upward-sloping and steeper, corresponding to higher

The

effect of

of default

an increase

unchanged

(if

initial debt.

in the interest rate is then either to leave the probability

next-period debt remains below the critical

increase the probability of default.

The

effect is

level), or to

again stronger the higher the

initial

14

Brazil

Figure 3 shows the effects of an increase in the interest rate on each

level of debt.

of the

two

[Figure

3.

loci.

The

The

1.4

probability of default as a function of the exchange rate.]

effects of the interest rate

on default

risk

and the

real

exchange rate

To summarize: The economy

is

values of monetary and fiscal policies,

C

((1

P

=

p and

characterized by two equations in

r,

r*,D,X and

e,

given parameters

for given

77,

#*,

(i,

A:

+ N(e) =

(6)

i>((~ + ^)l^ + (l-»)))D-X^

(7)

+ r) -

For lack of better names,

t>-\l

call

the

+ t*) -

first

(1

-

\)6*p)

the "capital flow" relation, and the second

the "default risk" relation.

The question we want

to answer

is:

Under what conditions

interest rate lead to a depreciation rather

From the two

initial debt,

equations, the answer

is

will

an increase

than to an appreciation?

straightforward:

The higher the

level of the

or the higher the degree of risk aversion of foreign investors, or the

higher the proportion of dollar debt in total government debt, then the

it is

in the

more

likely

that an increase in the interest rate will lead to a depreciation rather than an

appreciation of the exchange rate.

This

is

shown

in the three panels of Figure 4:

[Figure 4 a,b,c. Effects of an increase in the interest rate on the exchange rate]

p

High debt

Low

Figure

3.

debl

Default risk as a function of the exchange rate and the intere;

15

Brazil

•

Figure 4a looks at the case where the government has no dollar debt outstanding, so the probability of default

rate,

and the default

is

risk locus is vertical

the axes are reversed here)

It

.

independent of the real exchange

was horizontal

(it

shows the equilibrium

capital flow locus

is

The equilibrium

upward-sloping.

the equilibrium for high debt

is

two

for

of debt, and thus two different probabilities of default.

in Figure 3,

different levels

From Figure

low debt

for

but

is

1,

the

at A,

at B.

In this case, an increase in the interest rate shifts the capital flow locus down:

A

higher interest rate leads to a lower exchange rate.

risk locus to the right:

default.

The

A

size of the shift

is

•

and there

to A',

goes from

B

Figure 4b

still

proportional to the

more

rate leads to a depreciation.

A

is

likely it is that

As drawn,

initial level of debt.

So the

the increase in the interest

low debt, the equilibrium goes

at

an appreciation; at high debt, the equilibrium

to B', and there

is

a depreciation.

looks at the case where the government has no dollar debt

outstanding and the default risk locus

for

the default

higher interest rate increases the probability of

larger the initial debt, the

from

It shifts

is

shows the equilibrium

vertical. It

two different values of risk aversion, and thus two

capital flow locus. In response to

an increase

flow locus shifts down; the size of the shift

different slopes of the

in the interest rate, the capital

is

approximately independent of

the degree of risk aversion.

So, under low risk aversion, the equilibrium goes from

appreciation.

Under high

A

to A', with

risk aversion, the equilibrium goes

from

with a depreciation. Again, in this second case, the indirect

interest rate,

effect

on capital

exchange

•

through the increase

flows,

to B',

effect of the

in the probability of default,

dominates the direct

B

an

and the

effect of the interest rate

on the

rate.

Figure 4c compares two cases, one in which the proportion of dollar debt,

is

equal to zero, and one in which

debt

is

u. is

high.

at A, the equilibrium for high dollar

The equilibrium

debt

is

at B.

for

/x

low dollar

Low

debt

High debt

^

w

/

/

*"

B'

B,

.-

..••

A

,•*

,..*•****

1 r

..•*•"**

••»'

A'

—

Figure 4a.

Low and

high debt.

High

risk

aversion

A

/iB'

/X

B

./

••''

=

Low

«^

Ar>0

».:

A *£

'~~~~~~~^

:

jA'

>m :::::.'.''

Figure 4b.

Low and

high risk aversion.

risk a

Zero

dollar

debt

High dollar debt

•**

jT

^^—*•

A

^<- /

••**

B'

^

Figure 4c.

Low and

high dollar debt.

.

16

Brazil

An

increase in the interest rate shifts the capital flow locus down.

the default risk locus to the right, and the shift

the value of

/x.

For the low value of

/i,

to B', with a depreciation.

roughly independent of

the equilibrium moves from

with an appreciation. But for a high value of

B

is

u.,

It shifts

A

to A',

the equilibrium moves from

4

In short: high debt, high risk aversion on the part of foreign investors, or a high

proportion of dollar debt can each lead to a depreciation in response to an increase

in the interest rate.

All these factors were indeed present in Brazil in 2002.

to get a sense of magnitudes. This

A

2

what we do

question

of this section

specifically, I

is

model

and look

lead to an appreciation or, instead, to a depreciation.

step

as a guide.

estimate the two relations between the exchange rate and the

at whether, in conditions

such as those faced by Brazil in 2002, an increase in the interest rate

first

thus

in the next section.

to look at the evidence using the

probability of default suggested by the model,

The

is

look at the empirical evidence

The purpose

More

is

The next

must be to obtain a time

is

likely to

5

series for the probability of default, p.

We

can then turn to the estimation of the two basic equations.

2.1

From the EMBI spread

to the probability of default

A standard measure of the probability of default is

the

EMBI spread,

the difference

between the stated rate of return on Brazilian dollar-denominated and U.S.

dollar-

In this case, the convexity and concavity of the two loci suggest the potential existence of

another equilibrium with higher p and e. I have not looked at the conditions under which such an

equilibrium exists or not. I suspect that, again, if it does, it has unappealing comparative statics

4.

properties.

For readers wanting more background, two useful descriptions and analyses of events in 2002

and 2003 are given by Pastore and Pinotti [2003] and Cardoso [2004]. For an insightful analysis

of the mood and the actions of foreign investors, see Santiso [2004]

5.

17

Brazil

denominated government bonds of the same maturity. But,

clearly, the

EMBI

spread reflects not only the probability of default, but also the risk aversion of

foreign investors.

And we know

that their degree of risk aversion (or

their "risk appetite") varies substantially over time.

can separate the two and estimate a time

To make

The question

Invert C(.)

- p)(l + r $ -

[(1

)

and reorganize to

(1

Define the Brazil spread

)

as:

whether we

and rewrite

+ r*)] - 0*p) =

it as:

-N(e))

get:

+ r$ -

-p)(l

(1

inverse,

series for the probability of default.

progress, go back to the capital flow equation

C (£

is

its

(l

+

O=-

+-

9*p

C-'(-N(e))

6

S=

+ r*

1 + r$

1

l

The previous equation can then be

r$

1

-

r*

+ r*

rewritten to give a relation between the spread,

the probability of default, and the exchange rate:

(8)

The

interpretation of equation (8)

neutral, so 6*

conventional

first

=

and

straightforward: Suppose investors were risk

C = oo. Then S = p: The spread (as defined above, not the

EMBI spread itself)

term on the

is

would simply give the probability of default

right. If investors are risk averse

appear. First, on average, investors require a risk

6.

however, then two more terms

premium

for

holding Brazilian

This definition turns out to be more convenient than the conventional

$

the two move closely together.

empirically relevant values of r

,

—the

EMBI

spread. For

18

Brazil

dollar-denominated bonds. This risk premium

right.

Second, as the

demand

sloping, the rate of return

for Brazilian

is

given by the second term on the

dollar-denominated bonds

is

downward-

on these bonds must be such as to generate capital flows

equal to the trade deficit. This

captured by the third term on the

is

right. If capital

flows are very elastic, then changes in the rate of return required to generate capital

flows are small,

We

A

and

this third

term

small.

is

can now turn to the econometrics.

good semi- log approximation to equation

(8), if 9*

and p are not too

large, is

given by:

log

—

where a

l

•

+ C-

l

1/(1

{.)/{l

We

+

+r

clearly

r $ ),

and u

is

+u

a6*

equal to the last term in equation (8) divided by

%

).

9*

do not observe

that a good proxy for 9*

yield

S — logp +

,

but a number of economists have suggested

the

is

Baa

spread,

i.e

the difference between the

on U.S. Baa bonds and U.S. T-bonds of similar maturities.

words, their argument

reflect

movements

is

that most of the

in risk aversion, rather

movements

than movements

of default on

Baa bonds).

this suggests

running the following regression:

log

If

S=

we assume

c

+ b Baa

in the

that the

spread

(In other

Baa spread

in the probability

Baa spread

is

linear in 9*

,

+ residual

and recovering the probability of default as the exponential value of

c plus

the residual. This however raises two issues:

•

First, the residual gives us at best (\ogp

is

u), not (logp).

Approximating

be approximately correct only

if

small relative to changes in probability. This will in turn be true

if

the log probability in this

u

way

+

will thus

Brazil

19

capital flows are relatively elastic.

As

I

see

no simple way out,

I

shall again

maintain this assumption.

•

Second, the estimate of

be unbiased only

if

the

b,

and by implication, the estimate of (logp)

Baa spread and the

residual are uncorrelated. This

unlikely to be true. Recall that the residual includes the log of the prob-

is

ability of default.

aversion,

As we have

As the

ever,

Baa

seen in the model earlier, an increase in risk

which increases the Baa spread,

ability of default. Again,

I

see

effect of risk aversion

and

likely to

spread)

is

is

also likely to increase the prob-

no simple way out, no obvious instrument.

on the probability of default

be most relevant when

6* (and so,

1.

is

non

linear

how-

by implication, the

high, this suggests estimating the relation over subsamples

with a relatively low value of the Baa spread.

Table

will

I

shall

do this below.

Estimating the probability of default.

W

Sample

b (t-stat)

DW

OLS

1995:2 2004:1

0.37 (9.5)

0.34

AR1

1995:2 2004:1

0.31 (3.6)

0.84

0.89

AR1

Baa spread < 3.0%

0.16 (1.7)

0.85

0.89

AR1

Baa spread < 2.5%

0.15 (0.9)

0.88

0.90

P

0.46

Baa spread,

using

monthly data. All data here and below, unless otherwise noted, are monthly

aver-

Table

ages.

1

reports the results of regressions of the log spread on the

The spread

C-bond

defined as described above, based on the spread of the Brazilian

over the corresponding

difference

The

is

T-bond

rate.

The Baa spread

is

constructed as the

between the rate on Baa bonds and the 10-year Treasury bond

first line

reports

The estimated

OLS

rate.

results for the longest available sample, 1995:2 to 2004:1.

coefficient b is equal to 0.37.

The change

regimes which took place at the start of 1999, with a

in

exchange and monetary

shift

from crawling peg to

20

Brazil

floating rates

might expect

to the

Baa

and

inflation targeting, raises the issue of

this regime

line

two subsamples. The

3.0%; this removes

this

The second

removes

all

b

=

b in

first

eliminates

keep the longer sample.

all

bias in mind, the next

months

for

two

I

eliminates

months

all

lines look at

which the Baa spread

is

above

for

which the Baa spread

is

above 2.5%;

crisis),

and from

expect, the coefficient on b decreases, from 0.32 to

and to 0.15

in the second case.

use a series for

p constructed by using an estimated

below are largely unaffected

1 instead.)

coefficient

observations from 2001:9 to 2001:11, and from 2002:6 to

As we would

0.16. (Results

Table

I

With simultaneity

all

first case,

In what follows,

so

observations from 1998:10 to 1999:1 (the Russian

2000:9 to 2003:4.

0.16 in the

b,

shows the results of AR(1) estimation. The estimated

nearly identical.

2003:3.

One

spread; results using the smaller sample 1999:1 to 2004:1 give however

The second

is

stability:

change to have modified the relation of the Brazil spread

a nearly identical estimate for

b

subsample

if I

coefficient

use one of the other values for

Figure 5 shows the evolution of the

EMBI

spread, and the

largely together, except for

mean

and amplitude. The main difference between the spread and probability

series

constructed series for p.

The two

series

move

takes place from early 1999 to early 2002. While the spread increases slightly, the

increase

is

largely attributed to the increase in risk aversion,

and the estimated

probability of default decreases slightly during the period.

[Figure

5.

The

evolution of the

EMBI

spread,

and the estimated probability of

default.]

2.2

We

Estimating the capital flow relation

can now turn to the estimation of the two relations between the exchange rate

and the probability of

default.

Figure

5.

Spread and estimated probability of d

20.0

SPREAD

PROBA

17.5

15.0

12.5

10.0

7.5

5.0

2.5

-

——— — ——— — — —— — — ——

i

1

i

i

1995

i

i

I

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

1996

1997

1998

1999

— — — — — —— — —

i

i

\

I

i

I

i

i

i

I

i

i

i

2000

2001

200;

—

Brazil

The

21_

first is

the "capital flow" relation, which gives us the effect on the exchange

rate of a change in the probability of default.

equation

(6) is

good semi-log approximation to

given by:

log

The

A

=a-

e

b(r

-

r*)

+c

(pO*)

+u

(9)

e

exchange rate between Brazil and the United States

real

and a decreasing function

tion of the real interest differential,

is

a decreasing func-

of the risk

premium

the product of the probability of default times the degree of risk aversion of foreign

investors.

The

That there

rate

is

term captures

all

other factors.

a strong relation between the risk premium and the real exchange

shown

premium

floating

is

error

in Figure 6,

which plots the

real

for the period 1999:1 to 2004:1 (the

exchange

The

rate).

real

exchange rate

exchange rate against the

period of inflation targeting and

is

constructed using the nominal

exchange rate and the two CPI deflators. The risk premium

multiplying estimated p and

6*

risk

is

constructed by

from the previous subsection. (Using the

spread instead of p8* would give a very similar picture).

The two

series

EMBI

move

surprisingly together.

[Figure

6.

The

real

exchange rate and the risk premium]

Turning to estimation,

I

estimate two different specifications of equation

(9).

The

first

uses the nominal exchange rate and nominal interest rates; the second uses the

real

exchange rate and real interest

specification

is

that

it

rates.

The only

justification for the

nominal

involves less data manipulation (no need to choose between

deflators, or to construct series for

expected inflation to get real interest rates). 7

Results using the nominal specification are presented in the top part of Table

nominal exchange rate

7.

is

the average exchange rate over the month.

The

The nominal

Capital flows can be expressed as a function of the real exchange rate and real interest rates,

or as a function of the nominal exchange rate

is

2.

and nominal

interest rates.

a function of the real exchange rate. Thus, the nominal specification

is,

But the trade balance

stricto sensu, incorrect.

—

Figure

6.

Real exchange rate and risk premium

1999:1 to 2004:1

1.92

REALERATE

PTHETA

1.76 -

1.60

- 4

1.44 -

1.28

1.12

0.96

—

I

i

m

—

2002

i

i

i

i

r~r-

—

1

i

i

—

2003

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

22

Brazil

interest rate differential

rate

and the average

constructed as the difference between the average Selic

is

federal funds rate over the

month, both measured at annual

rates.

Table

2.

Estimating the capital flow relation

loge

(i-n

P 6*

DW

0.05

W

P

1

OLS

0.73 (1.8)

15.35 (6.1)

2

AR1

-0.21 (-0.9)

12.43 (13.1)

0.99

0.98

3

IV AR1

0.74 (1.3)

10.99 (2.4)

0.99

0.97

-

p6*

loge

(r

r*)

0.43

4

OLS

-0.05 (-0.2)

14.08 (11.6)

5

AR1

-0.08 (-0.4)

12.41 (12.5)

0.94

0.96

6

IV AR1

0.47 (0.6)

9.04 (4.3)

0.72

0.99

0.15

0.70

Period of estimation: 1999:1 to 2004:1. Instruments: Current and one-lagged value

of the federal funds rate and of the

Line

1

OLS

gives

differential is

tion.

Thus,

results.

The

risk

wrong signed and

Baa

spread.

premium

is

insignificant.

The

line 2 gives results of estimation

premium remains

highly significant; the interest rate

residual has high serial correla-

with an AR(1) correction. The risk

highly significant; the interest differential

is

correctly signed, but

insignificant.

Factors

left in

the error term

may however

affect

extent that the central bank targets inflation,

p and by implication p6 and,

may

also affect

simultaneity bias, there are two natural instruments.

funds rate,

second

is

i*,

which should be a good instrument

The

i.

To

first is

to the

eliminate this

the U.S. federal

for the interest differential; the

the foreign investors' degree of risk aversion, 9* (the

Baa

spread), which

Brazil

23

should be a good instrument for p8*. 8 Events in Brazil are unlikely to have

effect

on either of the two instruments. Line 3 presents the

results of estimation

using current and one lagged values of each of the two instruments.

premium remains

highly significant.

The

much

The

risk

wrong

interest rate differential remains

signed.

Results using the real specification are given in the bottom part of Table

real

exchange rate

the United States

is

is

constructed using

CPI

deflators.

constructed by using the realized

The

CPI

real interest rate for

inflation rate over the

previous six months as a measure of expected inflation. For Brazil,

two

different series.

States.

The second

Bank has

The

first

was constructed

in the

The

2.

same way

I

constructed

as for the United

uses the fact that, since January 2000, the Brazilian Central

constructed a daily forecast for inflation over the next 12 months, based

on the mean of

participants.

daily forecasts of a

These forecasts can

number

differ

and

of economists

markedly from lagged

financial

market

inflation; this

was

indeed the case in the wake of the large depreciation of the Real in 2002. Inflation

forecasts took into account the prospective effects of the depreciation

on

inflation,

something that retrospective measures obviously miss. Thus, the second

series is

constructed using the retrospective measure of inflation until December 1999, and

the monthly average of the inflation forecast for each

The

results of estimation using either of the

in Brazil are sufficiently similar that

series in

Table

I

month

two measures

after

for

is

expected inflation

2.

highly significant.

insignificant in the first

two

The

lines,

interest rate differential

wrong signed and

is

1

to

on the exchange

rate, I

3.

The

risk

correctly signed but

insignificant in the last line.

Given the importance of the sign and the magnitude of the direct

effect

1999.

present only the results using the second

Results from lines 4 to 6 are rather similar to those in lines

premium

December

interest rate

have explored further whether these insignificance

results for the interest differential were robust to alternative specifications, richer

8.

Note that p and

9* are uncorrelated

by construction. But p9' and

8" are correlated.

24

Brazil

lag structures for the variables, or the use of other instruments.

they appear to be. Once one controls for the risk premium,

consistent effect of the differential

The

on the exchange

specification in equation (9) reflects

earlier,

which assumed that movements

stant elasticity function of

movements

explored a specification that does not

in the

hard to detect a

expected exchange rate are a con-

exchange

make

this assumption,

b(r

-

rate. I

have also

and allows the

r* j

+ c( P 9*) +

e'

ue

(10)

and using the same

instruments as before, as they also belong to the information set at time

is

present, in Figure

7,

premium conditional on

estimation

and the

bands.

is

list

The

To

get around this problem,

values of d ranging from 0.8 to 1.0. For each value of

carried out, using the real specification, with

of instruments listed earlier.

future exchange rate

is

The bands

difference to the results.

d,

an AR(1) correction

are two-standard-deviation

taken to be the exchange rate six months

month

to nine

months ahead makes

Using the exchange rate more than nine months

ahead eliminates some of the months corresponding to the

lot of

The

the coefficients on the interest differential and the risk

ahead. (Using the exchange rate from one

little

t.

the usual problem of obtaining precise estimates of d versus

the degree of serial correlation of the error term.

I

ex-

rate:

This equation can be estimated using the realized value of

empirical problem

that

rate.

in the current

= a + d E[log e] -

it is

is

however the theoretical shortcut taken

change rate to depend on the expected exchange

log(e)

The answer

the information in the sample.)

The

crisis,

and thus

loses a

figure reports the results of estimation

using the nominal exchange rate and nominal interest rate specification; results

using the real specification are largely similar.

[Figure

7.

Estimated

on the exchange

rate]

effects

rate, as

of the risk premium and the interest rate differential

a function of the coefficient on the expected exchange

o

o

</)

£

0)

o

SMM

CO

+

v

(1)

*-*

,(D

(0

k.

LU

o

o

a>

O)

c

o

re

j:

H-j

o

X

cr

"O

.CD

0)

.O

o

CD

o

it-

C5

CD

u

a>

v2

3

D)

i

CO

CD

CO

.«

<4-»

C

CD

o

O

o

m

ai H=

O CO

o

u

s3

o

C

4m

CO

1^

Q

a.

c

o

c

LU

5—

i

4-1

X

C/>

CO

to

d)

CD

O

o

E

Mm

^

+» o

0)

0)

ac

4

"Q

li.

r~-

o

(ejeq+^d)

uo juspupoo

CD

O

UD

O

-*

o

(»j-j)

CO

o

CM

o

T-

o

o

o

uo juapujaoo

T-

o

CN

o

25

Brazil

The

lesson from the figure

sistently positive.

The

is

that the coefficient on the risk

on the

coefficient

premium remains

interest differential is consistently

con-

wrong-

signed.

In short, the empirical evidence strongly supports the

first

theoretical argument, the effect of the probability of default

In contrast (and as

there

central link in our

on the exchange

often the case in the estimation of interest parity conditions),

is

empirical support for the conventional effect of the interest rate

is little

differential effect

on the exchange

rate.

Estimating the default risk relation

2.3

The second

relation

we need

to estimate

is

the "default risk" relation, which gives

the probability of default as a function of the expected level of debt, which

depends on the exchange

among

The

rate, the interest rate,

and the current

itself

level of debt,

other factors.

relation

we need

to estimate

is:

V

= ^{ED')+up

where, in contrast to the theoretical model,

next-period debt

is

elected),

we need

to recognize the fact that

example a lower threshold

which are captured here by up

The theory

(11)

if

a

leftist

government

be

is

.

suggests assuming a distribution for the distance of next-period debt

from the threshold, and using

believe there

is

it

to parameterize

not enough variation in the

ip(.). I

have not explored

debt-GDP

ratio over the

allow us to estimate the position of the cumulative distribution function

precisely).

may

uncertain even in the absence of default, and there

shifts in the threshold (for

I

rate.

So

I

specify

and estimate a

p

-

ip

linear relation:

ED' +

u„

this, as

sample to

ip

function

Brazil

26

Next-period's debt

itself is

given by the equation:

Wj,

+r

i-p

1

y

\-v

D% e + D R

X

This equation does not need however to be estimated.

In estimating equation (11),

The

•

first is

That there

I

consider three different proxies for ED':

simply D, the current level of the net debt-GDP

is

a strong relation between

D and p

is

shown

ratio.

in Figure 8,

plots the estimated probability of default p, against the current

ratio, for the

also

made

debt-GDP

period 1990:1 to 2004:1.

That expectations

is

which

clear

of future debt matter

beyond the current

level of

debt

however by the partial breakdown of the relation during

the second half of 2003. Debt has stabilized, but had not decreased further.

In contrast, the estimated probability of default, has continued to decrease.

From what we know about

that period, the likely explanation seems to be

the growing belief by financial markets that structural reforms, together

with a steady decrease in the proportion of dollar debt 9 implied a better

,

long run

fiscal

situation than

debt. For this reason,

[Figure

8.

The

I

was suggested by the current evolution of

explore two alternative measure of ED':

relation of the estimated probability of default to the

debt-GDP

ratio]

The

•

first

measure of ED'

is

the

mean

forecast of the

debt-GDP

year ahead. Since January 2000, the Brazilian Central

Bank has

ratio

one

collected

daily forecasts of the debt ratio for the end of the current year

and

for

the end of the following year. Using average forecasts over the month,

I

construct one-year ahead forecasts of the ratio by using the appropriate

9.

The proportion of dollar debt,

21% in January 2004.

2002 to

net of

swap

positions, has decreased

from 37% in December

Figure

GDP

Debt to

8.

and p of default

ratio

1999:1 to 2003:5

10.8

63.0

61.2

9.6

59.4

8.4

57.6

7.2

55.8

54.0

6.0

52.2

4.8

50.4

3.6

48.6

46.8

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

1999

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

2000

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

2001

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

i

2002

2003

i

2.4

Brazil

27

weights on the current and the following end-of-year forecasts. For example

the one-year ahead forecast as of February 2000

is

constructed as 10/12

times the forecast for debt at the end of 2000, plus 2/12 times the forecast

for

debt at the end of 2001.

differently

from current debt, and so

does not explain the decrease in p during the second half of 2003.

forecast of debt

does not

many

A

years ahead might do better, but such a time series

exist.)

The second measure

•

turns out that, during 2003, this measure

move very

of expected debt does not

still

(It

of

ED' is the realized value of the debt-GDP six months

ahead, instrumented by variables in the information set at time

results are largely similar

if I

t.

The

use realized values from one to nine months

ahead. (As for exchange rates earlier, using values more than nine months

ahead eliminates important

crisis

months from the sample.)

I

shall discuss

instruments below.

The

results of estimation are given in Table 3.

and

Lines

1

debt.

They confirm the

OLS

2 report the results of

visual impression of a strong relation

the probability of default. There

and 4 report AR(1)

used, weaker

when

OLS and AR(1)

regressions, using either current or forecast

The

results.

forecast debt

is

evidence of high serial correlation, so lines 3

relation

is

results are likely

between debt and

becomes stronger when current debt

is

used.

however to

suffer

from simultaneity

bias.

Any

factor other than debt that affects the probability of default will in turn affect

expected debt. For example, financial markets

of

may have concluded that

the election

Lula would both lead to higher debt, and a higher probability of default at a

given level of debt.

affects

A

natural instrument here

expected debt, but

is

unlikely to be affected

The same instrument can be used when

The

may wonder how

is

again the

Baa

spread, which

by what happens

in Brazil.

10

using the realized value of debt six months

Baa spread can be used

as an instrument in both the capital

because it enters multiplicatively (as 9* in p0") in the

capital flow equation, and can therefore be used as an instrument for p9* in that equation.

10.

flow

reader

and the default

the

risk equations. It

is

28

Brazil

ahead (the third measure of debt

t.

The next

3.

consider) as

,

it is

in the information set at

six lines report results of estimation using the current

values of the

Table

I

Baa spread

time

and four lagged

as instruments.

Estimating the default risk relation

D

p on

1

OLS

2

OLS

3

AR1

4

AR1

5

IV

6

IV

7

IV

8

IV AR1

9

IV AR1

10

IVAR1

D' forecast

D' actual

0.15 (3.4)

0.18 (3.7)

DW

0.23

0.15

0.41

0.21

0.42 (10.4)

0.02 (0.2)

0.23 (3.4)

0.23 (3.8)

0.21 (3. 1)

&

P

0.99

0.89

0.86

0.75

0.17

0.11

0.41

0.18

0.48

0.02

0.38 (3.4)

0.22 (0.8)

-0.28 (-1 •4)

0.98

0.88

0.96

0.73

0.97

0.65

Period of estimation: 1999:1 to 2004:1. Instruments: Current and four lagged values

of the

Baa

spread.

Lines 5 to 7 report the results of

IV

estimation, without an

coefficients are largely similar across the three

Lines 8 to 10 give the results of

results using the first

correction.

The

give a negative

the table.

IV

correction.

measures of debt, and

estimation, with an

AR(1)

The

significant.

correction.

The

two measures of debt are roughly unchanged by the AR(1)

result of estimation using six

and

AR

months ahead debt (instrumented)

insignificant coefficient. It

is

the only negative coefficient in

Brazil

29

In short, the empirical evidence strongly supports the other central link in the

theoretical model, the link from expected debt to the probability of default. This

in

turn implies that any factor which affects expected debt, from the interest rate

to the

exchange

2.4

Putting things together

rate, to the initial level of debt, affects the probability of default.

Given our two estimated

in the

relations,

we can determine whether and when an

increase

—through the conventional

on the

a depreciation—through

domestic interest rate will lead to an appreciation

interest rate channel

—

or, instead, to

its effect

probability of default.

In a way,

we already have

the answer, at least as to the sign. In most of the

specifications of the capital flow relation,

differential to

is

we found the

effect of the interest rate

be either wrong signed, or correctly signed but

insignificant. If this

the case, only the second channel remains, and an increase in the interest rate

will

always lead to a depreciation...

So, to give a chance to

specification

both channels,

I

use, for the capital flow equation, the

which gives the strongest correctly signed

on the exchange

rate, line 2 of

loge

=

Table

constant

For the default risk equation,

I

effect of the interest rate

2:

-

-

0.21(r

r*)

use line 6 of Table

+

3,

12.43 (9*p)

which

is

representative of the

-

/z)

results in the table:

p

=

constant

+

0.23

=

constant

+

0.23

ED'

,,

1

-

1

+r

—p

+

—— -

X6*p

-

1

p

.

,

[fie

+

.,

(1

N1

^ - „,

X]

£>

30

Brazil

•

The

direct effect of

an increase

given by the coefficient on (r

an increase

—

in the interest rate

r*).

on the exchange rate

is

Thus, given the probability of default,

in the Selic of 100 basis points leads to

an appreciation of 21

basis points.

•

The

increase in the interest rate however also leads to an increase in ex-

pected debt, and thus to an increase in the probability of default, which

leads to a depreciation.

The strength

of this indirect effect depends

investors, 9*; the initial

relation

For the

debt-GDP

ratio,

on the

D, and

between the market and foreign investors'

first

three parameters,

I

risk aversion of foreign

its

9*

=

0.56.

For the

a different value,

effect

on the

it

last, I

/i;

the

risk aversion, A.

use as benchmark values the average values

of these three variables for the period 1999:1 to 2004:1:

and

composition,

use a value of A

=

D = 0.53,

0.50 (While one

fi

=

may

0.50,

choose

turns out that the specific value of A does not have

much

results.)

Under these assumptions, the equations above imply an

the exchange rate of 279 basis points.

interest rate of 100 basis points

is

The net

effect of

indirect effect

an increase

on

in the

therefore to lead to a depreciation of 258

basis points.

Table

4.

Effects of an increase in the Selic of 1 percentage point on the

exchange

rate, for different values of D,/x

Aloge(%)

and

9*

Aloge(%)

Aloge(%)

D =

0.13

0.00

H=

0.00

0.91

9*

=

0.10

-0.03

D=

0.33

0.59

H=

0.30

1.48

9*

=

0.20

0.22

D = 0.5S

2.58

^i

=

0.50

2.58

9*

=

0.56

2.58

D =

8.57

H

=

0.70

12.11

9*

=

0.80

21.2

0.63

Brazil

31

Table 4 gives a sense of the sensitivity of the

Benchmark

•

The

effect to values of

D,

\l

9*.

and

values are boldfaced.

first set

of columns

show the

effects of different initial

debt levels (keep-

ing the other parameters equal to their benchmark values)

For debt-GDP ratios of 13%, the

the exchange rate

is

an increase

effect of

The

roughly equal to zero:

in the interest rate

direct

and

on

indirect effects

roughly cancel. The indirect effect rapidly increases with the debt ratio.

With a debt

ratio of

terest rate

a depreciation of 8.57%. For debt ratios above 70%, we are

is

63%, the

effect of

a one percentage point in the

in the case discussed in the theoretical section,

where there

is

in-

no longer

an equilibrium. The interactions between the probability of default and the

debt are too strong. (This

may

explain the high volatility in the

EMBI

and

the nervousness of foreign investors in 2002.)

•

The next two columns show the

effects of different

proportions of dollar-

denominated debt (keeping the other parameters equal to

their

benchmark

With no dollar-denominated

debt, the exchange rate barely moves

in response to the interest rate.

As

the proportion increases however, the

fx

=

0.7,

is

no longer an equilibrium. The

value).

effect increases rapidly.

for values

above

0.8,

For

there

the depreciation reaches 12.11%.

Brazilian government has steadily reduced

\l

in 2003

may

And

fact that the

help explain

why

the estimated probability of default decreased steadily while the level of

debt remained relatively high.

•

The

last

two columns show the

effect of different degrees of risk aversion

on the part of foreign investors. For low

actually appreciates, but by very

little.

risk aversion, the

But, again, as the degree of risk

aversion increases, the exchange rate depreciates.

the depreciation reaches 21.2%.

0.8,

than

0.8,

exchange rate

And

the equilibrium again disappears.

As

risk aversion reaches

for risk aversion slightly higher

32

Brazil

Conclusions and extensions

3

The model and the

When

fiscal

of debt

is

empirical work presented in this paper yield a clear conclusion.

—

conditions are wrong

denominated

And

when debt

in foreign currency,

high-an increase in the interest rate

an appreciation.

i.e.

fiscal

is

more

when

is

high,

when a high proportion

the risk aversion of investors

is

than to

likely to lead to a depreciation

conditions were indeed probably wrong, in this specific

sense, in Brazil in 2002.

The

limits of the

argument should be clear as

well.

To go from

and

these conclusions to a characterization of optimal monetary

model and

this

fiscal policy in

such an environment requires a number of additional steps:

•

The model should be made dynamic. The same

at work.

But

this will allow for a

to the data. In a

mechanisms

basic

be

will

more accurate mapping from the model

dynamic model, the probability of default

will

depend on

the distribution of the future path of debt, not just "next-period debt".

•

The model needs

to be nested in a

nominal

This

rigidities.

that the central

needed

is

for

model with an

two reasons: To

bank has indeed control

treatment of

explicit

justify the

assumption

of the real interest rate;

and to

derive the effect of changes in the real exchange rate on inflation.

•

The model focused on the

effects of the interest rate

the real exchange rate. There

is

on

inflation

through

obviously another and more conventional

channel through which an increase in the interest rate affects inflation,

namely through the

effect of the interest rate

on demand, output, and

in

turn, inflation.

When and

whether

this

second channel dominates the

issue. I speculate that, in

be very strong. The

first is

an empirical

may

not

been very high over the

last