REVITALIZING KUWAIT'S EMPTY CITY CENTER

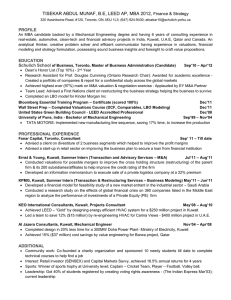

advertisement