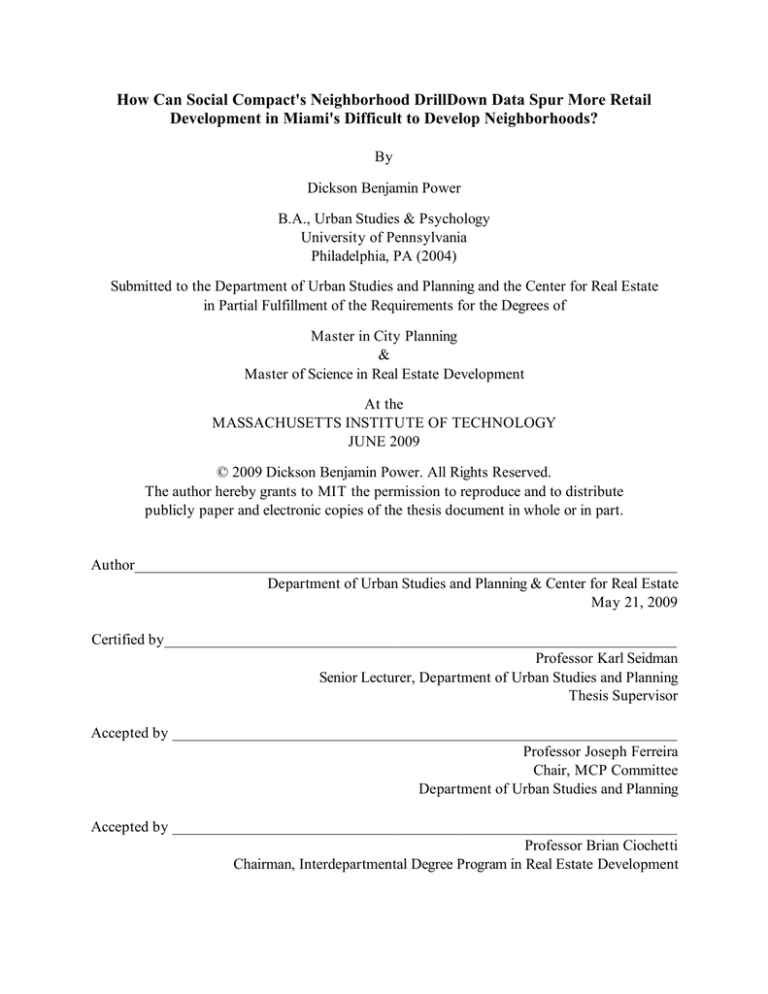

How Can Social Compact's Neighborhood DrillDown Data Spur More Retail

advertisement