American Educational Results

advertisement

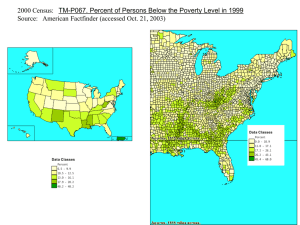

American Educational Results At first glance America's educational record looks good. Officially, 99 percent of the population 14 years of age and over is literate. Moreover, some 86 percent of 25 to 29 year olds; have completed high school. A quarter of the population aged 25 to 29 have graduated from college. Today we spend twice as much on education as on defense, and the American university system is widely acknowledged to be the best in the world. Now for the bad news. While virtually everyone may be literate as measured by years of school completed, functional illiteracy- that is, the inability to read and understand the language effectively at about a sixth-grade level- is still widespread. During the early 1970s, when the military draft was still in effect, one of every four men taking the Armed Forces qualifying test was judged functionally illiterate. This means that they could not easily read a daily newspaper or instructions for operating machinery. Today, roughly one in eight adults in the United States still remains functionally illiterate. The problem is especially serious among immigrants and the poor. Half of those heads of households with incomes below the poverty level cannot read at an eighth-grade level. The most complete and accurate data on the current level of functional literacy in America comes from the Educational Testing Service's study of 26,000 persons chosen to represent a cross section of American adults. They found that, while almost everyone can read at a basic level, an estimated 90 million Americans over age 16 are not fully equipped for the literacy requirements of the workplace. In practical terms this means they have difficulty calculating the difference between sale and regular prices; they cannot figure out a bus schedule or mentally compute the tip on a restaurant meal. 15-16 Moreover, those that are the worst off don't even know that they don't know. Of the 42 million American adults who fall in the bottom fifth in reading ability, 71 percent think they read very well. The reality is that such persons are largely excluded from skilled jobs. They almost certainly are outside the cybernet information networks that college students take for granted. Educational Inequality How to equalize educational opportunity remains perhaps the major educational problem. Public school systems, particularly those in large cities, have not been very successful with students who lack home preparation or strong family motivation. Innercity primary and secondary schools are sometimes viewed even by their teachers as little more than holding tanks, leaving nearly three-quarters of large-city school children reading below grade level. After decades of promises and programs, many inner-city schools still remain woefully deficient. The educational reformer Jonathan Kozol says in Savage Inequalities that the nation maintains two separate and unequal school systems, one for poor minority innercity children and another for the more affluent. Poor children sometimes attend Third World condition schools with poorly qualified teachers, while there are well-equipped schools with good teachers only a bus ride away. The National Assessment of Educational Progress Tests indicate the average reading level of black 17-year-olds is about that of white 13-year-olds. Twelve years of schooling in inner-city schools is not equivalent to 12 years in a high-income suburban system. While federal and state governments have established a wide range of special education programs, inner-city schools remain the nation's problem schools. Their plight is analogous to that of Sisyphus, the cruel king of Corinth in Greek mythology, who was condemned eternally to push a rock uphill only to have it roll down again when he neared the top. Declining Standards? Middle-class schools also have problems. The good news is that the proportion of high school students taking core academic courses has increased from 13 percent in the mid 1980s to 47 percent today. The bad news is that the level of educational knowledge is not increasing. A high school diploma no longer guarantees that the student has mastered even minimal math, reading, and comprehension skills. To insure that all high school students graduate with at least basic reading and writing skills, many states now require students to obtain some form of "literacy passport" before receiving a high school diploma. To receive the passport, however, most states require only that twelfthgrade students be able to read at an eighth-grade level, and some states set the high school passing level even lower. In an attempt to reverse declining standards, the nation's governors met in 1989 at the first educational summit and set educational goals for the year 2000. At the third educational summit meeting at the end of 1999, however, the governors confessed that none of the eight goals set by the governors 10 years earlier were yet within reach. The 1998 National Assessment of Educational Progress indicated that only 1 percent of twelfth-graders reached the "advanced" stage in writing skills, while about a quarter were "proficient," and 22 percent failed to meet "basic" standards. Some educational experts believe that these problems are overstated and much of the discussion about failing schools is a near-myth. Most observers, however, believe the problems are very real. The Third International Mathematics and Science Study, the largest and most thorough examination of what students know in mathematics and science, suggests there are serious problems with American schools. Some 500,000 students in 41 nations were tested. American eighth-graders ranked 28th in mathematics and 17th in science. American high school students consistently score lower than students from other industrial nations. This poor standing is attributed both to America's low academic expectations and to America's shorter school year. The average school year in the United States is 180 days, compared to 210 days in Germany and 244 days in Japan. Also, when in school American students spend less than half as much time studying core academic subjects such as science, English, math, and history as do students in Germany, France, or Japan. American students think their schools are too easy and want to be challenged. Some 75 percent say they would study harder if schools gave them tougher tests and 74 percent say schools should not pass them to the next grade only when they have learned what's expected of them. Grade Inflation While course expectations have been declining, grade inflation, where grades of "A" are routinely given in high school (and college) for work that would have received only a "B" or "C" a generation earlier, has become the norm. The College Board, sponsor of the SAT (Scholastic Assessment Test), announced in 1998 that while students' grades are going up, students' knowledge and performance levels are declining. The number of students taking the SAT test who have an "A" grade average has increased dramatically over the past 10 years to 38 percent, but the SAT scores of those "A" students has declined an average of 12 percent. By 1996 the average SAT scores had declined to where, in order to restore the SAT to its old norm of 1,000, the test had to be reconfigured, and all scores were raised by approximately 100 points. Thus, a combined score of 1,000 today is equivalent to a score of 900 before 1996. There is agreement that American primary and high school standards are low, but less on how to solve the problem. One response is simply to do away with traditional grades. The state of Oregon is replacing all high school letter grades by statewide exams that test specific proficiencies. As of 2001, letter grades and grade point averages in Oregon high schools will be replaced by tests that measure having achieved certain necessary performance standards; the goal is to switch the focus from the students' grade to whether they actually know the subject. Educational and business leaders often advocate establishing national standards for what students should know. President Clinton proposed in 1998 establishing national standards of learning, but the Republican Congress strongly disagreed, feeling establishing national learning standards would interfere with the rights of local school boards. Universities also are experiencing grade inflation and decreasing coursework requirements. Students are usually unaware that many introductory course textbooks now are routinely "dumbed down" to a tenth-grade or lower reading level (this text hasn't been "dumbed down"). With high schools not teaching students basic skills, even prestigious colleges have been forced to run remedial programs. Over one-fourth of college freshmen require remedial mathematics, writing, or science courses. Some open-admission universities such as CCNY (City Colleges of New York) are now moving to raise standards and eliminating remedial courses. Students who are unprepared for regular college-level work must first take remedial courses offered by local community colleges. The answer seems to be that successful inner-city parochial and public schools demand more of their students. Unlike many inner-city schools, successful schools assume that all students can do good work and insist that they do so. Performance levels are not lowered, and dropping out of school is strongly discouraged. All students are expected to work hard and be successful. Parochial schools also insist that parents take an active role in the education of their children. This is a requirement that most local public schools cannot enforce. Academic expectations and parental involvement have payoffs. Inner-city minority children attending parochial schools are four times more likely to graduate and three times more likely to go on to college than those in the local public schools. It is clear that inner-city schools can successfully motivate and educate students. The tragedy is that many inner city schools don't do so. However, even among the worst school systems in the nation there are some signs of hope. In 1987 then Education Secretary William Bennett cited Chicago's system as being the nation's worst. It may not have been the worst large-city system, Detroit's and Washington, D.C.'s usually share that dubious honor, but it was in serious trouble. More recently, in 1999, William Bennett praised the Chicago system as, "a model of accountability and flexibility. What changed things was a radical shake-up of the system. In desperation, the state legislature in 1995 gave Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley control over the Chicago public schools, and he immediately installed Paul Vallas as school CEO. Vallas set achievement test goals, removed 36 principals, fired tenured teachers who were not performing, and sent poor-performing students to summer school. Chicago's attendance and test scores are still low by national standards, but they have risen dramatically since 1995.