by U.S. Some Recent Developments Paul L Joskow

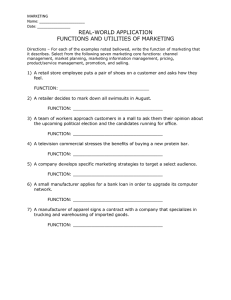

advertisement