BASEMENT hmii''

advertisement

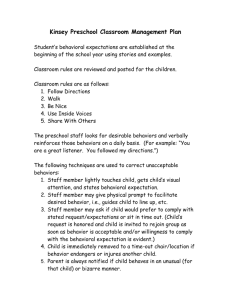

BASEMENT hmii'' / -r^^^^. ALFRED P. WORKING PAPER SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT THE PREDICTIVE ACCURACY OF BEHAVIORAL EXPECTATIONS: TWO EMPIRICAL STUDIES by Paul R. Warshaw McGill University and Fred D. Davis Sloan School of Management MIT Working Paper // 1450-83 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 50 MEMORIAL DRIVE CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139 THE PREDICTIVE ACCURACY OF BEHAVIORAL EXPECTATIONS: TWO EMPIRICAL STUDIES by Paul R. Warshaw McGill University and Fred D. Davis Sloan School of Management MIT Working Paper // 1450-83 General Self-understanding Moderates the Accuracy of Self -reported Behavioral Expectations Paul R. Warshaw McGill University and Fred D. Davis Massachusetts Institute of Technology Running Head: Self -understanding Self -under standing 1 Abstract Wilson While Nisbett and Ericsson & researchers other between self-report has been self-understanding self-presentation. the ability and the willingness to accurately somewhat must self-understanding. self-understanding is a Namely, from self-understanding domains The overlooked. differentiated be Further, behavioral must present be differentiated manuscript potentially argues important self-understanding behavioral expectations findings are is warranted. is and discussed issues those that of relates from that of to general general individual difference variable which has been neglected in the literature. between general (e.g., 1980) argue about the accuracy of self-reported data, Simon, the distinction specific and (1977) The relationship the accuracy of self-reported and provocative preliminary reported which suggest that further research on the topic Self -under standing 2 Prediction of individual social psychological has Ajzen Fishbein, (e.g., behavioral concerned with in theorizing and research (for example, see Ajzen Bonfield, 1975), organizational (e.g., and political important been long & Related applied domains like the consumer (e.g., Ryan Fishbein, 1980). & behavior predictions Katerberg Horn, Hinkle, & 1980) because Hulin, & 1979) fields are also accuracy their has for the success of planning and policy-making significant implications activities. individual-level behavioral forecasts have Generally, upon intention measures predict (e.g., Ajzen argued, first Ajzen prediction purposes expectation (or behavioral is his/her Recently, however, it has been and Hartwick self-prediction) his/her expectation is an habits, abilities and individual's performing Warshaw & and intention situational factors, Hartwick as confounded Hartwick, Note 2). moderate & as Hartwick, anticipated in press). have delineated conditions expectation is likely to be behavioral predictor, although these two a been that well as (in press) often with factors behavior, beliefs, attitudes, social norms, intentions, under which an individual's behavioral concepts have self-reported specified a changes in these determinants (Warshaw, Sheppard superior to Behavioral (BE). cognitive appraisal of volitional and non-volitional behavioral determinants: Warshaw, Sheppard and press) (in that the more pertinent construct for (Note 1), subjective probability of based on Sheppard based those whose behavior we wish to by Fishbein, 1980). & Warshaw, by subsequently by reported been the in the literature (Sheppard, The present research is more concerned predictive accuracy of behavioral Self -understanding 3 expectations per particular, In se. investigation of the influence of self-understanding on the individual's an predictive the of a preliminary results accuracy of level of general his/her behavioral expectation is reported. Accuracy of Self-reports there has been much controversy and confusion In general, literature regarding Wilson (1977) the argue accurately report validity of self-reported data. individuals that their on mental are processes, conscious of the products of such processes. the Nisbett and observe to although they may be Wilson Nisbett and or have on the grounds that their distinction between process and been refuted tautological product is unable in Nevertheless, other (Smith research Miller, & White, 1978; 1980). suggests that an individual's ability to accurately self-report is a function of the type of phenomenon they are being asked to report on. For one's memory tend performance example, self-reported beliefs about not to be accurate (Herrman, 1982) and process-oriented, think-aloud verbal protocols of thought processes are accurate only under certain circumstances However, choice, self -predict ion intellectual & 1980). Simon, achievement, vocational job performance and the like are at least as accurate as assessment methods Osberg, of (Ericsson 1981). with Hence, organizes various which research self-related they is have other been compared (Schrauger needed to develop a taxonomy £i that phenomena with respect to individuals' ability to accurately self-report on them. Research should be shifted Self -under standing 4 to the issue of when, not whether, self-reported data are accurate. relationship Research on the attitude-behavior steps toward addressing behavior can be accurately self-reports issue the predicted often a & performing toward behavioral expectation since attitude Attitude-type understanding our to major taken (as opposed to whether) attitudes. from pertinent especially are when of has behavior of is major determinant of behavioral expectation (Warshaw, Sheppard Hartwick, in press). In fact, prior to Fishbein and on behavioral intention, 1975) work concept extensive review was brought capability The predictive by Wicker's question into attitude-behavior of (e.g., researchers viewed attitude as the best self-predictor of future behavior. the attitude Ajzen's research, which of (1969) found the relationship between verbal expression of attitude and subsequent overt behavior to be weak as generally reported in the literature. was representative concept as a of an era of disenchantment predictor of behavior (e.g., with Deutscher, This work the attitude Ehrlich, 1966; 1969). Reversing this trend, recent work has the utility of the generated optimism attitude concept (e.g., Kelman, 1974). toward an attitude object have been shown to be toward Attitudes predictors better of multiple-act behavioral criteria with respect to the object than of any particular act, while more specific attitudes toward the act tend to be better predictors of single act behavioral criteria than are attitudes toward the object (Fishbein Based upon & Ajzen, 1974; Fishbein & Ajzen 1975). an extensive review of 109 attitude-behavior studies, Ajzen Self -under standing 5 and Fishbein (1977) argue that attitude predicts behavior measures when the much better attitude and behavior correspond in specificity of with respect to target, action, context and Including time. a term reflecting the social influence of significant referents has been shown power predictive to increase well as (Ajzen predictive accuracy of attitudes declines attitude measurement of Kelley 1978; & factors impede Warner & Mirer, Schwartz, 1974; behavior the DeFleur, 1969). elapsed when time when and 1978), (Davidson is between Jaccard, Romer, 1981; predictor useful a & The situational Jaccard, 1978; & attitude Thus, Fishbein, 1973). increases (Davidson behavior and L of behavior under appropriate circumstances. Self-presentation Versus Self-understanding Research on conditions affecting data has increasingly on the role of focused For our purposes, we distinguish two difference variables: related to self -understanding the subject's willingness accurately consider self-report. the research design, different causes. individual differences. individual of self-presentation and those accurately relate Although distinction self -understanding phenomena self-reported relate Self -presentation phenomena . to self -understanding phenomena to of categories broad related those accuracy the to the blurred between to be crucial self-report, subject's in the whereas ability literature, self-presentation from the clarify to we and standpoint of insofar as the error related to each arises from To to very the distinction, we will first discuss Self -under standing 6 established self-presentation phenomena, which have been well Distinguishing literature. self-understanding, will we self-understanding is domain-specific between argue then the in and general domain-specific that established in the literature, whereas somewhat general self-understanding is a relatively neglected concept. Self- presentation Self-presentation phenomena (e.g., Goffman, have Schlenker, 1959; Edwards (1957), Crowne Marlowe and Building 1980). developed (1979) scale a self-monitoring individuals appropriately in given a are social Low concerned more that the self-monitors Snyder Tanke, 1976; & behaving about tend As based behavior guide to would attitude-behavior relation is be been found self-reports (Turner modeling framework components of to £ to attitude. be attenuated for k Zanna, Olson & Fazio, 1980). A £ White, Thus, with associated Peterson, 1977). separate the their expected, 1982; related concept, public self-consciousness (Fenigstein, Scheier 1975) has upon Snyder those high in self -monitor ing (Ajzen, Timko Swann, 1976; High than low self-monitoring situation behavior based more on their internal states. research shows More recently, self-monitoring. of individuals, and tend to control and guide their situational contingencies. individual an difference scale of social desireability response bias. Snyder the work of on developed (1964) extensively with dealt been and Buss, invalid more Romer (1981) employs true multiple giving & a causal self-presentational research traditions provide Self -under standing 7 evidence that individuals high in concern for self -presentation tend to be less willing to accurately report their attitudes. Self- understanding Domain-specific Self -under standing (as opposed to the willingness) the ability We draw self-understanding to self-presentation, In contrast the distinction Domain-specific self-understanding. Markus' the nature of domain-specific are "cognitive self-understanding experience, that organize and refers to to specific a self-schemata theory investigates (1977) self-understanding, about generalizations general and internal knowledge of behavioral determinants relative behavioral domain. guide the the where self, self-schemata derived processing of from past self-related information contained in the individual's social experiences" (p. Markus (1977) provides a provides basis for evidence possession that individual's an "confident behavior on schema-related dimensions" (p. Two concepts from (Sherif & & Hovland, attitude theory, of 64). self -schemata self-prediction of 63). the latitude of rejection Hovland, 1961) and affective-cognitive consistency (Rosenberg 1960), recently have construe to be related to and Zanna to to accurately self-report. domain-specific between relates (1977) use been used to explore issues that we domain-specific the attitude-behavior consistency latitude is of self -understanding . Fazio rejection notion to show that significantly moderated by the amount Self -under standing 8 of direct degree experience, of certainty with which the attitude held, and how well-defined the attitude is, all relative to Norman behavioral domain. a poorly-defined domain) and achieve results behavioral specific which are consistent with that operationalization Chaiken and Baldwin . (1981) further suggest that affective-cognitive consistency as useful a measure schematicity of specific a and Chaiken and Baldwin (1981) use (1975) affective-cognitive consistency to measure well- versus attitudes (within is the in context may of serve Markus' self -schemata theory. General Self -understanding From these domain-specific various research self -understanding self-report accuracy. self-understanding, the differences in general self-reported behavioral Given the question traditions, emerges as self-understanding expectations? moderator a of of of domain-specific arises: would individual importance naturally concept the moderate accuracy the of In contrast to domain-specific self-understanding, general self-understanding refers to one's internal knowledge of his/her behavioral determinants in general, not relative to any specific behavioral domain. The general self-understanding concept from related concepts in the should literature. self-awareness theory posits that attention at be differentiated Wicklund's any given (1975) moment is Self -understanding 9 directed either toward the self or toward external events. state is also refered to as the state of aroused, be can himself /herself in voice. The example for having by mirror or listen to a accuracy of attention, individual an recording a and view his/her of own self-reports of judgements of past and future events (Pryor, Gibbons, Wicklund, feelings (Gibbons, self-focused The former Fazio Carver, Scheier & Hood, & Hormuth, 1979) is present and 1977) increased under conditions of heightened self-focused attention. Fenigstein, Scheier and Buss (1975) developed and private previously, the state in and Turner of public of self-focused Peterson the accuracy self-reports. of self -consciousness has been associated self-reports (Scheier, Buss & self -consciousness may be an Buss, mechanism by be accurate Private Turner, 1978). 1978; important to high private predictively with public phenomena) In addition, in attention. found (1977) self-consciousness (an example of self-presentation related to scale self-consciousness that assesses individual differences the proportion of time spent As indicated a general which self -understanding is developed. Self-perception (Bem, 1972) is change which says that a theory of attitude formation individuals infer their attitudes and other internal states from observation of their own overt contexts in which the behavior ambiguous or uninterpretable" significant role self-understanding. in the and behavior and the occurs when "internal cues are weak, (p. 2). process For a long time, by Self-perception which may individuals self-perception was viewed play a gain as a Self -under standing 10 with competed thoery that Festinger's theory for explaining attitude attempted Cooper (1977) to change cognitive (1957) phenomena. resolve dissonance Fazio, Zanna and this controversy by arguing that dissonance and self-perception are actually complementary theories, and by delineating appropriate their domains self-awareness, self-consciousness application. of self-perception and from self-understanding, they are clearly related. While distinct are Future research on self-understanding should take these bodies of theory and research into account Although general self-understanding has literature, the construct has with respect to for example, expectation (BE) measures. overlooked been implications for self-report accuracy; predictive the accuracy Under domain-specific self -understanding, domain independent to self-understanding different domain (Markus, 1977). as domain-specific If with respect then would expect a that self-understanding correlation across variety individuals would a of evidence behavioral the highest evidence a bility between these extremes. well exhibit A priori, we general in BE/behavior mean low in general the lowest mean BE/behavior score. The value for individuals who are medium in general should lie a behavioral their high are who in as should domains. sample of behaviors, while those self-understanding should behavior people systematic differences in the predictive accuracy of largely is people differ in general self-understanding, expectations across behavioral of self-understanding with respect to behavior in one of the in Namely, self-understanding we expect that overall to accurately predict one's pattern of behaviors is positively Self -under standing 11 related to the individual's general self-understanding level. The study reported below is a hypothesized relationships preliminary between examination general self-understanding and the accuracy of BE forecasts for eleven behaviors. maximally to so as dissociate these of The study was designed the measurement of self-understanding from the self-reported behavioral expectation measurement, as an effort to rule possibility the out self-understanding measure mind. subjects that with relevant the responded to behavioral the domains in Although any true assessment of general self understanding would require that a multi-item, validated scale be developed and applied, the present study uses only a crude self-report measure, reflecting our primary purpose which is not to substantively research the topic here, but rather to point out that the field important individual pilot results which difference suggest has overlooked a potentially variable and to show some provocative the value of researching general self- understanding. Method Subjects Subjects were 107 undergraduate student volunteers east coast university. from a large The sample contained 57 males and 50 females. Prospects were recruited from four small coed dormatories by aides who knocked randomly on doors of students' private rooms. all undergraduates who were approached agreed to participate. research Nearly Self- understanding 12 Procedure Each subject was interviewed in his or her private dormatory separate on three likelihood procedures Several each sitting. a connect instrument (first interview) with the separate questionnaire at employed were would subjects that completing occasions, minimize to subsequent self-prediction questions pre-testing some attitude questions for Included therein measure: "I myself at was the university research 0123456789 don't 10 marketing To further dissociate the two parts of this study, one class project. month expired between the first questionnaire and subjects had interviews. second indicate second The 9-point on probable/improbable scales their behavioral expectations of performing eleven separate behaviors during the upcoming five days (e.g., drinking alcohol, skipping class). those understand Research aides who administered the second and third instruments claimed to be students collecting data for their each of team. following simple general self-understanding know myself well all." interview Those who subjects that they were told a and separate First, groups of interviewers were used for each part of the study. personality the self-understanding the behavioral elicitations (second and third interviews). administered the room acts most frequently These mentioned particular during prior behaviors were focus group discussions among 25 non-sample member students regarding non-sex typed behaviors that students commonly perform. one week after the second, subjects During the third checked performed each behavior during the designated once, once, or not at all (a 'don't off time remember' interview, whether they had period more than category was also Self- understanding 13 provided) . In addition questionning separating to from behaviorally-or iented the encouraged responses were further subjects illusion that were providing symbol which honest , created anonymous responses. his/her write questionnaire. their on self-understanding quest ionning procedures by interview, the subject was told not to identifying general the When name the At each or other completed, personality instrument was placed by the subject in a sealed the envelope, while the expectation/behavior questionnaires were each collected via procedure. ballot box However, leaving the subject's private inscribed subject's the questionnaire. room for analysis data occasion, immediately upon interviewer surreptitiously his/her just-completed each the room, number Hence, each subject's matched later on questionnaires three could a personality and self-prediction tasks; they were their questionnaires. Hence, the dropped from the No subject reported an awareness that their identity was matched to be During post-experimental purposes. few subjects postulated some connection between debriefing, only study. on a being we felt reasonably assured that untainted data were gathered. Results and Discussion Twenty-four subjects were excluded from the data analysis. were deleted because they perceived that the first and second parts of the study were connected. were not home Three The remaining 21 were excluded because they for either the second or third of the three interviews. Self- understanding 14 Since the not-at-homes contained members each of rough proportion to its representation in the sample at large group in eight high, eight medium and five low), (i.e., self-understanding denigrated by their absence. In total, the results were not 83 subjects provided analyzable data. Based upon responses their to general the self-understanding question, subjects were divided into high (n=30), medium (n=31) and low groupings. (n=22) between behavioral calculated for each For group, expectation each summarized in Table of (BE) eleven the findings behavior and behaviors. test measures were Results are 1. Insert Table The Spearman rank order correlations supported 1 about here the hypothesis that general self-understanding affects one's ability to self-predict and that those who are low self -predictors. .34 (low), Fisher general z .60 in general self-understanding are the Namely, the mean £s across all eleven behaviors (medium) and .53 (high). transformations of the rs showed self-understanding [F(2) = 6.16, a worst were An analysis of variance on significant main effect for 2"^ .01]. Further, as Self -under standing 15 hypothesized versus and low medium Hence, significant. both the low versus high (t(20)= 2.58, 2< .02) priori, a (t^(20)= group low the 3.88, 2< .001) differences was less able, across all eleven behaviors, to predict their performance than were both the self-understanding high general subjects. medium high the inadequacies in our group. rough validated, multi-item scale high result found r a (n.s.) Perhaps this unexpected result stems from general would self-understanding certainly give measure. more a estimate of general self-understanding and perhaps reverse versus and However, contrary to our priori expectations, the medium group evidenced a higher mean than did were here. Since nobody self-understanding, those who rate themselves the reliable medium complete has extremely A high the on direct self-report scale are perhaps overstating their case, especially compared with values. lower those individuals who, more realistically, give slightly problems Related self-understanding are: 1) with asking someone their people who have little self-understanding may be precisely those individuals who are unlikely to believe this true of themselves (one more misunderstanding on their part); and is 2) self-presentation phenomena may introduce bias. While not conclusive, these results strongly suggest research on general self-understanding is warranted. that future Self -under standing 16 Reference Notes 1. Ajzen, From I. behavior. Chapter Action-control: Springer, 2. Sheppard, B. a more intentions in to From to action: appear in J. cognition A Kuhl to & theory J. behavior of planned Beckmann (Eds.)f . New York: preparation. H., Warshaw, general for publication, P. R. t Hartwick, theory of reasoned action 1983. . J. On the need for Manuscript submitted Self -under standing 17 References Ajzen, I. Fishbein, £< theoretical analysis and Psychological Bulletin Ajzen, I. & Fishbein, M. predictors of I. & , research. 22, as Journal of Personality behaviors. 1973, variables 41-57. Understanding attitudes and predicting Fishbein, M. Englewood Cliffs, . empirical of A 1977, 8±, 888-918. , specific social behavior review relations: Attitudes and normative and Social Psychology Ajzen, Attitude-behavior M. N. J.: Prentice Hall, 1980. Ajzen, I., Timko, C. White, & attitude-behavior relation. Social Psychology Bern, D. J. Chaiken, S. and the Journal 1982, £2, of and the Personality and 426-435. Self -percept ion theory. Advances in York: , Self -monitor ing J. In L. Berkowitz experimental social psychology (Vol. (Ed.), 6). New Academic Press, 1972. & Baldwin, M. effect of W. Affective-cognitive salient self-perception of attitudes. Social Psychology , 1981, 41, consistency behavioral information on the Journal of 1-12. Personality and Self -under standing 18 Crowne, D. P. Marlowe, D. & Evaluative Dependence Davidson, A. R. & 1979, Deutscher, Journal J. Wiley, Personality of of and in 1964. Variables that moderate Results relation: Studies the longitudinal a Social Psychology , 1364-1376. 37, Words I. New York: . Jaccard, J. attitude-behavior survey. The Approval Motive; deeds. and Problems Social , 1966, 13 , 235-254. Edwards, A. The social desireability variable in personality L. assessment and research Ehrlich, H. New York: Attitudes, behavior and the American Sociologist Ericsson, K. A. & H. & Zanna, M. the strength Journal 398-408. of , 1969, Simon, Psychological Review Fazio, R. . of , H. 4, A. Dryden, 1957. intervening variables. 35-41. Verbal reports as data. 1980, 82, 215-251. P. the Experimental Attitudinal qualities relating to attitude-behavior Social Psychology relationship. , 1978, 14 , Self -under standing 19 Fazio, R. Zanna, H., M. self -percept ion: proper domain application. 1977, , Fenigstein, A., Scheier, M. private Cooper, & Journal theory's each of and Experimental of 464-479. 13, F. Dissonance J. view integrative An of Social Psychology P. & Buss, self-consciousness: A. Assessment Journal of Consulting and Clinical Public H. theory. and Psychology , dissonance . and 1975, 43 , 522-527. Festinger, L. A theory cognitive of Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1957. Fishbein, M. of Ajzen, & I. Attitudes toward objects as predictors single and multiple behavioral criteria. Review , Fishbein, M. behavior 59-74. 1974, 81, & Ajzen, An Belief, I. introduction , Ajzen, understanding voting external variables. Hinkle, in American Ajzen In I. Understanding attitudes Englewood Cliffs, N. theory to & I. attitude, Addison-Wesley Reading, Massachusetts: Fishbein, M. Psychological J.: and , R. intention M. predicting research and . 1975. Predicting elections: & and Effects of Fishbein social Prentice-Hall, 1980. and (Eds.), behavior . Self- understanding 20 The presentation of self in everyday Goffman, E. Doubleday City, NY: Herrman, D. & Garden . Company, 1959. Know thy memory: J. life The use of questionnaires Psychological Bulletin assess and study memory. to 1982, 92 , , 434-452. Horn, P. W. Katerberg, , examination turnover. R. three of Journal of & Hulin, approaches Applied C. to Comparative L. prediction the Psychology 1979, , of 64 , 280-290. Kelley, S. Mirer, P. & W. The simple American Political Science Review , act of voting. 1974, 68, 572-591. Attitudes are alive and well and Kelman, H. employed gainfully American Psychologist sphere of action. in the The 1974, 29 , , 310-324. Self -schemata and processing Markus, H. self. 35, Journal of information about Personality and Social Psychology , the 1977, 63-78. Nisbett, R. E. L Wilson, T. D. Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. 1977, 84, 231-279. Psychological Review , Self -under standing 21 Norman, Affective-cognitive R. conformity and behavior. Psychology Pryor, J. , 1975, X., Wicklund, R. Journal of Personality A., Fazio, R.H. , 1981, 41, Rosenberg, M. Journal of J. Personality and Social Psychology & Hovland, C. Cognitive, I. of attitudes. In M. (Eds.), Attitude organization al. Haven, Conn.: & of , 562-576. behavioral components J. & 513-527. 1977, 45, A person-situation causal analysis of self-reports attitudes. Ryan, M. Journal of Personality and Social Self-focused attention and self-report validity. Hood, R. et. attitudes, 83-91. 32, B., Gibbons, F. Romer, D. consistency, Yale University Press, Bonfield, E. consumer behavior. H. affective Rosenberg, J. and and change . New 1960. The fishbein extended model and Journal of Consumer Research , 1975, 2, D. M. 118-136. Scheier, M. F., Buss, Self-consciousness, aggression. 133-140. A. self H. report & of Buss, aggressiveness Journal of Research in Personality , 1978, and 12, Self -under standing 22 Schlenker, B. Impression R. Schrauger, J. S. & Osberg, T. Schwartz, Psychological Bulletin instability Temporal S. as attitude-behavior relationship. Social Psychology Sherif, M. 1978, Hovland, C. & and Contrast R. cognitive 36, 322-351. 90.' moderator a Journal of Personality and Judgement; Assim ilation Miller, F. processes: A & , D. reply 1978, 85, Self-monitoring processes. Limits to on Nisbett perception . Academic Press, 1979. of Wilson. and 355-362. In L. Berkowitz Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. York: the of 715-724. Social I. 1981, . Effects in Communication and Attitude Change Psychological Review Snyder, M. of Yale University Press, 1961. New Haven: Smith, E. , accuracy relative The M. judgements by others in psychological self-predictions and assessment. Belmont, . 1980. Wadsworth, California: Relations Interpersonal and Social Identity, Self-concept, The Management: (Ed.), 12). New Self- understanding 23 Snyder, M. Tanke, E. & are more consistent 1976, 501-517. Snyder, M. 44, Swann, W. & politics of than others. actions When , 1976, reflect predictive validity The Journal of Personality and Journal of Research in measures. , 1034-1042. 34, typical of attitudes: and self-consciousness, Consistency, G. people Some Journal of Personality impression management. and Social Psychology Turner, R. Behavior and attitude: D. personality maximal Personality the , 1978, 12, 117-132. Turner, R. G. Peterson, & self-consciousness and G. & concept: Attitude Defleur, M.L. Social between American Sociological Review Warshaw, P. R. , Sheppard, B. and self-prediction appear in Communication of Bagozzi R. . and constraint intervening variables , H. 1977, as private and emotional expressivity. Consulting and Clinical Psychology Warner, L. Public M. Journal of 45, 490-491. an interactional distance social attitudes as action. and 1969, 3£, 153-169. , & goals (Ed.), Greenwich, CT: The Hartwick, J. and Chapter to behavior. Advances JAI Press, in in intention Marketing press. Self -under standing 24 White, P. Limitations on verbal reports of internal refutation of Nisbett and Wilson and of Review Wicker, A. , 1980, Psychological Bern. relationship The verbal and overt responses to attitude objects. Social Issues Wicklund, R. A. , 8). Zanna, M. New York: P., 1969, in self-awareness. Experimental An M. & In L. Berkowitz Psychology (Vol. Social Fazio, R. individual Journal of Personality and 432-440. Journal of Academic Press, 1975. Olson, J. consistency: of 41-78. 25, Objective (Ed.), Advances A 105-112. 87, Attitudes versus actions: W. events: H. Attitude-behavior perspective. difference Social Psychology , 1980, 38 , Self -under standing 25 Footnotes Correspondence concerning the article should be sent Warshaw, Faculty of Management, McGill Street West, Montreal, Quebec, H3A 1G5. University, to 1001 Paul R. Sherbrook Self -under standing 26 Table 1 Spearman Rank Order Correlations Between Behavioral Expectations (BE) and Behaviors for High, Medium and Low General Self-understanding Groups Self-reported General Self-understanding Criterion Behaviors The Accuracy of Behavioral Intention Versus Behavioral Expectation for Predicting Behavioral Goals Paul R. Warshaw McGill University and Fred D. Davis Massachusetts Institute of Technology Running Head: Predicting Behavioral Goals Predicting Behavioral Goals 1 Abstract Researchers have largely overlooked the distinction between an individual's behavioral intention and his/her behavioral expectation as predictors of his/her own behavior. Moreover, the distinction between purely volitional behaviors and behavioral goals , the latter of which may be impeded by such non-volitional factors as lack of ability, lack of opportunity, habit and environmental impediments, has also been blurred in the literature. based upon a Behavioral expectation is theorized to be cognitive appraisal of one's behavioral intention plus all other behavioral determinants that one is aware of. Therefore, the present research argues and gives evidence that while behavioral expectation and behavioral intention may have similar predictive accuracy for volitional behaviors, behavioral expectation is adequate while behavioral intention may be inadequate for prediction of the accomplishment of behavioral goals. Predicting Behavioral Goals 2 Predicting individual behavior has long interested social psycholoThe conceptual underpinning for gists and other applied researchers. much of this work is Fishbein and Ajzen's intention model Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & (Ajzen & Although the field has Ajzen, 1975). generally accepted their proposal that the best predictor of an individual's future behavior is his/her present behavioral intention to perform that behavior (BI) , Warshaw, Sheppard Hartwick (in press) have & argued that behavioral intention and behavioral expectations (BE) have been confounded in the literature. BI is measured by asking individuals to indicate whether or not they intend to perform a behavior on some subjective probability scale) , (usually while BE is measured by asking individuals whether or not they will perform a behavior (also on some subjective probability scale). Thus, while BI is a statement of con- scious intention, BE is a self -predict ion of one's own behavior. Although BE has been used inadvertantly and inappropriately to operationalize intention (e.g., Bentler et al. (in press) & Speckart, 1979), Warshaw theorize that BE is predictively superior when criterion behavior is habitual or mindless (Langer, 1978) , b) a) the the indi- vidual is able to foresee changes in his/her current intention during or prior to the time in question, or c) the individual is able to foresee impediments to performing the behavior, such as lack of ability, lack of opportunity, habits or environmental impediments. Thus BE is based on an individual's cognitive appraisal of all volitional and non- volitional behavioral determinants of which he/she is aware: beliefs, attitudes, social norms, present intentions, habits, abilities and situational factors, as well as anticipated changes in these determin- Predicting Behavioral Goals 3 (Warshaw, et al., ants in press). As formulated by Fishbein and Ajzen is theorized to be the immediate volitional behavior . (1975) , behavioral intention psychological determinant of purely Thus it does not apply when the probability of performing a behavior given that it is not consciously attempted is greater than 0.0 performing than 1.0 a (the case of habit), or when the probability of behavior given that it was consciously attempted is less (the case of behavioral impediments). is routinely, The intention model although inappropriately, applied in contexts where habits or behavioral impediments are operative (Warshaw, et al., in press). We shall refer to behaviors where lack of ability, lack of opportunity, habits or environmental impediments prevent the performance of the behavior given that it is attempted as behavioral goals goals are a special case of goals . Thus behavioral (Warshaw, et al., in press), including non-observable outcomes as well. the latter Behavioral goals have not been distinguished from purely volitional behaviors in the literature that attempts to predict behavior from intentions. For purely voli- tional behaviors, BE should be based largely on an individuals intention (BI), and BE and BI should both be predictive of behavior (B) . However, for behavioral goals, BE should reflect considerations of behavioral impediments that BI does not include. for purely volitional behaviors expectation (BE) and behavior and behavior (B) (B) , Thus it is hypothesized that the correlations between behavioral and between behavioral intention (BI) will all be significant; whereas for behavioral goals the correlations between behavioral expectation (BE) and behavior , (B) will be significant while the correlations between behavioral intention Predicting Behavioral Goals 4 (BI) and behavior (B) will be non-significant. Method Subjects Subjects were 39 male and female undergraduate students who were enrolled in two introductory marketing courses at a large east coast university during the summer of 1982. The students voluntarily participated in the study during class time. Procedure Subjects completed two questionnaires. The first, administered on a Monday and Tuesday, pertained to student activities the following This questionnaire asked BI and BE questions regarding four weekend. behaviors. Two of these behaviors were purely volitional behaviors while two were behavioral goals. The method of selecting these four behaviors involved having thirty-seven non-sample-member students rate each of several acts as either a behavior or a goal for them during the upcoming week. Behaviors were defined for them as acts which "nothing much would prevent you from carrying out the act during the- upcoming week, assuming you intended to perform it," while goals were defined as those acts for which "lack of ability, lack of opportunity, habits or environmental impediments might prevent you from carrying out an intent to perform the act during the upcoming week. " Predicting Behavioral Goals 5 Subjects rated various acts as behaviors or goals for them on five point semantic differential scales whose endpoints were "definitely a behavior for me" point 5). (scale point 1) (scale Those two acts most strongly rated as behaviors (i.e., eating ice cream (x = and going swimming 1.6) strongly rated as goals = 3.3) and "definitely a goal for me" (i.e., (x = 2.2)) and those two most talking with a goodlooking stranger and finishing all my unfinished school work selected as the experimental behaviors. (x = (x 4.2)) were Namely, eating ice cream and going swimming were the purely volitional behaviors while talking with a goodlooking stranger and finishing all my unfinished school work served as examples of behavioral goals. The scales used to measure BI and BE were 11-point (0 to 10) semantic differential scales with endpoints "highly likely/highly unlikely" (the ordering of these endpoints was reversed for half the subjects) . Regarding BE, subjects were asked to "please indicate the likelihood that you will actually perform each act listed below sometime this upcoming weekend." this upcoming weekend follows: I Questions were of the form: will [act]." "Sometime For BI, the instruction was as "Please indicate what your intentions are at this very moment regarding your performing each act listed below sometime this upcoming weekend. We are not asking about what you think your inten- tions are going to be this weekend; rather, please focus only upon your present intentions." I Questions were of the form: intend to perform [act] "At this very moment, sometime this upcoming weekend." When subjects had completed the questionnaire, they were instructed to inscribe their initials on its face. During the following Monday and Predicting Behavioral Goals 6 Tuesday, subjects answered the second questionnaire, self-reporting their performance or nonperformance of each act on questions of the form: "This past weekend, did you [act]? Yes No." Once again, each subject's initials were requested so that their two questionnaires could be matched. Results and Discussion The results of this study strongly support our hypotheses. shown in Table 1, the correlations between BE and B for the two purely volitional behaviors goals (r However, = As .307 and (r = .362) .441 and .415) as well as for the behavioral are all significant at the p < .05 level. the correlations between BI and B were significant only for the two purely volitional behaviors (r = each case) but not for the behavior goals .476 and (r = .340; p < .05 in .091 and .171; n.s. in each case) Insert Table 1 about here. These results suggest that researchers should verify that the assumption of conscious volitionality is met when using intention measures for prediction, and that behavioral expectation may be alternative in the cases where this assumption is not met. a useful Predicting Behavioral Goals 7 In fact, hiMclh since several researchers have argued recently that much behavior has nonintentional determinants (e.g., Langer, 1978; Zajonc, 1980; Zajonc & Markus, 1982), behavioral expectation may be superior to intent for predicting the performance of many "behaviors" of interest to social scientists. Predicting Behavioral Goals 8 Ajzen, Behavior Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Fishbein. M. & I. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: . Bentler, P. M. G. & Fishbein, M. I. & Models of Attitude-behavior relations. Speckart. Psychological Review 1979, , E. J. In J. H. Addison-Wesley Harvery, W. J. Ickes R. P. , . 1975. Rethinking the role of thought in social interaction. in Attribution Research Warshaw, 452-464. 8j6, Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior Ajzen. Reading, Massachusetts: Langer, Prentice Hall, 1980. , B. H. (Vol. Sheppard Kidd (eds) Hartwick. Prediction of Goals and Behavior. in Marketing ComiTiunications F. , New Directions New York: Halsted, 1978. 2). J. & R. & In R. The Intention and Self- Bagozzi (ed). Advances Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press, . in press. Feeling and Thinking: Preferences Need No Inferences. Zajonc, R. American Psychologist Zajonc, R. & H. Markus . , 1980, 25.' 151-175. Affective and Cognitive Factors in Preferences. Journal of Consumer Research , 1982, 9, 123-131. Predicting Behavioral Goals 9 Footnotes Correspondence concerning the article should be sent to Paul R. Warshaw, Faculty of Management, McGill University, 1001 Sherbrook Street West, Montreal, Quebec, H3A 1G5. Predicting Behavioral Goals 10 Table 1 Spearman Correlation Coefficients Between Cognitive Measures (i.e., Intentions, Self-Predictions) and Performance of Two Types of Acts Variables Correlated Behaviors Purely volitional behaviors BI/B BE/B : Go swimming 476** .441** Eat ice cream 34C* .415** Behavioral goals : Finish all ones unfinished schoolwork 091 307' 171 362' Talk with a goodlooking stranger N = 39 for each table entry. Note: BI = Behavioral Intention BE = Behavioral Expectation B * p < .05 ** £ < .01 = Behavior ^353 Uii6 MIT 3 I IP.RARIES TDfiD DOM MT2 TbQ Date Due Lib-26-67 fN3W3S'''