GAO UNITED NATIONS PEACEKEEPING Lines of Authority for

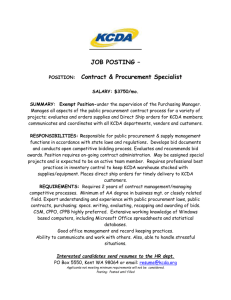

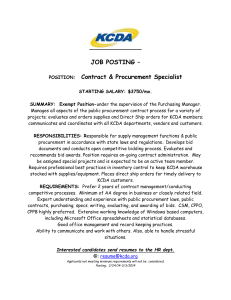

advertisement