AMPHIBIOUS COMBAT VEHICLE Some Acquisition Activities Demonstrate

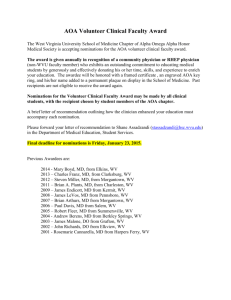

advertisement