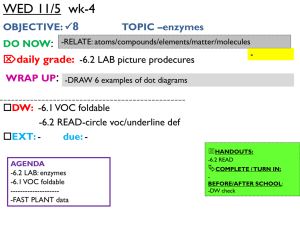

T E C F

advertisement