PLANT FOR LIFE Briefing Report 8: December 2004

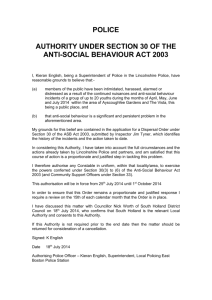

advertisement

PLANT FOR LIFE Briefing Report 8: December 2004 Ross Cameron and Sarah Swan University of Reading Health Benefits Associated With The Natural Environment Recent reviews of the health benefits (both physical and psychological) associated with the natural environment and urban green space, provide compulsive arguments for proper provision and management of green space to help combat current and predicted health problems (Morris, 2003; Henwood, 2001; Seymour, 2003). Indeed, it is suggested that this issue should be central to government policy following the philosophy that ‘Prevention is better than Cure’. Although the subject matter in these reports is wider than the use of amenity plants in the landscape or domestic garden, the implications are important for the horticultural and landscape industry. These reviews cover familiar territory with respect to theories put forward by Ulrich and the Kaplans, but additional new and important information is also provided. The report by Morris, ‘Health, Well-Being and Open Space’, points out that ‘The Environment’ has been seen in both negative and positive terms. Unfortunately, Health Specialists have tended to accentuate the negative aspects, and rather taken for granted the positive components. The term “environmental health” tends now to be associated with pollution, poisonous plants and animals, potentially dangerous microbial organisms and risk factors associated with certain activities (e.g. pesticide application, working with chain saws etc.). However, Morris also points out there has been a long tradition of positive factors influenced by the environment – healing powers of certain plants through herbal medicines, spa waters for drinking and bathing, fresh air and scenic beauty. It is also now being realised that outdoor activity provides scope for relaxation, refreshment, ‘escape from the everyday’ and the chance to form social relationships. DEFRA studies suggest 80 % of population visit the countryside per year for pleasure and recreation, and a recent MORI pole suggests 80 % of adults believe a visit the countryside is a vital counterbalance to the stresses of daily life (Anon, 2004a). Nevertheless, these statistics are presented against a background where 7/10 people do not take enough exercise and even amongst the young, only 4/10 could be described as physically active. The problems of inactivity and associated health problems are acerbated in the lowest social-economic groups. The benefits of exercise are linked with both physical and psychological health and helps prevent coronary heart disease, stroke, vascular diseases, diabetes through obesity, hypertension and raised blood cholesterol. In terms of mental health, exercise relieves anxiety, enhances well-being and can help offset depression. Physical exercise does not need to be strenuous to have a significant effect on people’s health, well-being and productivity; regular exercise for 30 minutes a day being appropriate for adults. By dealing with the issues that prevent people from becoming ill in the first place, it has been estimated the NHS could save £30 billion per year. Promoting exercise through ‘green activities’ such as cycling, walking in parks / countryside or being involved in gardening or conservation / landscape work, is important as these activities may have additional benefits. For older people and the disabled there was less stigma attached to these activities compared to competitive sports. There was some evidence that drop out rates were less compared to say, joining a gym, and interestingly in one survey participants were shown to walk faster when outdoors compared to the treadmill in the gym! New initiatives such as ‘green gyms’ are trying to combine the advantages of physical exercise and exposure to the natural world, as well as doing useful environmental or conservation work. Studies have shown that reasons for not taking up activity and exercise have been cited as: Not enjoying exercise, being too old, lack of time or other commitments, ill health / disability, lack of surroundings or facilities, limited skills, confidence, money or difficulties with transport. Two disadvantages particularly associated with outdoor activities were fears over safety and concerns regarding environment and weather. Indeed, The National Urban Forestry Unit claimed that the reason for a lack of use of urban green space was largely due to poor maintenance issues or they were often disconnected or difficult to reach, or were perceived as unsafe. It is some of these factors that government needs to address to encourage more active participation in exercisebased activities. In terms of psychological benefits, one of the positive factors associated with green space and natural landscapes is there restorative effect from stress and mental fatigue (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989). Korpela and Hartig (1996) suggest that restorative experiences figure in emotional and self-regulatory processes through which individuals develop an identity of place. He found people often went to their favourite places to relax, calm down and clear their mind of negative events. Favourite places identified, most often incorporated elements of greenery, water or scenic quality. Such places have coined the term ‘therapeutic landscapes’. Morris’s report concludes that there are 5 key ways in which exposure to the natural environment is beneficial:• Enhanced personal and social communication skills • Increased physical health • Enhanced mental and spiritual health • Enhanced spiritual, sensory and aesthetic awareness • Ability to assert personal control and increased sensitivity to one’s own wellbeing Henwood’s report, also engages with issues in health development and the way interactions with the environment can help. It covers many of the issues outlined by Morris, but also provides in more detail the factors that cause physiological stress including key social issues (employment, income, crime, rural v urban lifestyles) that can lead to so-called psychosocial stress. This report finishes by outlining how the agencies involved in countryside management can promote health and prevent illness in the population, and how these factors may move up the agenda in terms of priority. The report by English Nature (Seymour, 2003) deals with social policy in greater depth and how changes in policy within the UK can benefit mankind, and at the same time biodiversity. Promoting The Use Of Green Space Through Quality Planning And Management In urban areas the use of parks and other green spaces is strongly influenced by the quality of the environment and peoples perceptions on safety. CABE Space have produced a policy note in relation to preventing anti-social behaviour in public spaces (Anon, 2004b). Rather than investing in close-circuit television, and traditional security measures such as gates and fencing, CABE Space argue much can be down to reduce vandalism and other anti-social behaviour through two ‘solutions’ – ‘Target hardening’ and ‘Place making’. ‘Target hardening’ is the re-designing of facilities and equipment to make them near-indestructible, and less susceptible to theft, vandalism and abuse. ‘Place making’ involves proper investment in good design, attractive new facilities and a high standard of maintenance to ensure maximum benefit to the public. The report highlights three important criteria. 1. People’s behaviour adapts to the environment around them and that a ‘no-tolerance’ approach to vandalism and quick repair of any damage inhibits repeat behaviour. 2. The research also shows that initial investment in the quality of the park brings long term savings. Up to 11% of a park’s maintenance budget can be spent on repair or replacement, but proper investment at the start can reduce this. 3. The reinstatement of park keepers and wardens can re-assure the public as well as provide a deterrent to anti-social behaviour. References Anon (2004a). National Trust hails natural health service, Horticulture Week, 9 September, 2004 p5. Anon (2004b). CABE Space policy note- Preventing Anti-Social Behaviour in Public Spaces. http://www.cabespace.org.uk/data/pdfs/preventing_asb.pdf Henwood K. (2001). Issues in Health Development: Environment and Health – Is there a role for environmental and countryside agencies in promoting benefits for health? Health Development Agency. http://www.hda-online.org.uk/downloads/pdfs/environmentissuespaper.pdf Kaplan, R and Kaplan, S. (1989). The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Korpela, K. and Hartig, T. (1991). Restorative qualities of favourite places. Journal of Environmental Psychology 16:221-33. Morris N. (2003). Health, Well-being and Open space, Literature Review. http://www.openspace.eca.ac.uk/healthwellbeing.htm Seymour, L (2003). Nature and Psychological well-being. English Nature Research Reports No 533. English Nature, Peterborough, UK. http://www.ukpha.org.uk/cgi-bin/admin/uploads/documents/English%20Nature%20%20psychological%20well-being%20report.pdf Campaign financed with aid from the European Union