EXPLORING THE PROCESS OF DECONSTRUCTION OF USED GARMENTS IN

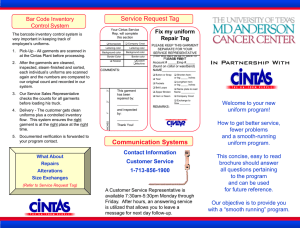

advertisement