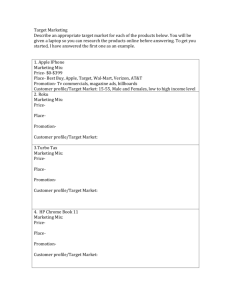

F : K Y

advertisement

FOOD FOR THOUGHT : KNOWING YOUR RELATIONSHIP TO FOOD BY D IANE D EPKEN & KATHY SCHOLL Have you noticed that food, and all permutations of food are gaining traction in our culture? Food systems, local food, food and obesity, sustainable food, slow food, food desserts, cooking food, food reality shows, food game shows, competitive cooking; name your media outlet, and there will be food on it. And yet, food is a physical necessity and cultural glue that holds our body and our society together. In any culture across the world, food is central to any family and community events or celebrations. Food is also deeply imbedded in our physiology and biochemistry, from nutrient absorption, and satiety signals, to dopamine release. How do we gain a greater awareness of our complex relationship with food? Perhaps through a deeper understanding of the core of food within today’s food system, we may be better equipped to respect and reflect the complexity of food for ourselves and for those around us. Food for Thought will briefly introduce ecological model systems approach to understand the complex issue of food. ECOLOGICAL THEORY Bronfenbrenner’s Bio-ecological Systems Theory, also known as Human Ecology Theory, was originally developed with a child development focus and has since been adapted and applied to health promotion and education, and leisure, youth and human services research. This theory posits that human development is influenced by the interaction among and between a variety of social and ecological relationships. At system theory’s core; understanding the components of a system is done best by looking at the relationships between these interacting systems rather than taking the system apart and looking at each component in isolation. Bronfenbrenner’s five environmental system layers include the micro system, the mesosystem, the exosystem, the macro system, and the chronosystem. This model has matured through Bronfenbrenner’s and others’ work (Darling, 2007). While other models have used different terminology to describe these layers, all ecological modeling approaches seek to assist us in understanding the rich and complex contextual interplay that helps to deconstruct complex and multifaceted issues affecting us. Food certainly qualifies. Figure 1 Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Model FOOD AT THE CENTER In this short report, we will point to a few recent research trends as examples of the interacting parts of our food webs. However, the unique twist is that we will posit that rather than an individual being placed at the center of the systems circles, we are placing an apple (symbolic of all food) at the center. The system’s concentric circles then focus on our individual biology and one’s digestive track as one part of complex collaborative mesosystem layer. We then telescope our view on our local food system, including the production, processing and distribution of our foodstuffs (or getting the food from the farm to your table) as another layer of a complex, competitive/collaborative endeavor. Finally, we widen our lens to see how food and human’s interact in another complex, collaborative system; the earth and the soil, water and air. Figure 2 Ecological Food Systems Approach Chronosytem: Time and chronological events Macrosystem: Soil & Earth Exosystem: Food systems & policies, food availability Mesosytem: Apple (Food) context and connections: Person, Community, Culture Microsystem:The Apple MICROSYSTEM LENS : T HE A PPLE Apples are grown as the fruit of an apple tree and have been traced back to human use over 4,000 years ago. We will skip our current domestic apple varieties and apple orcharding practices and focus on the apple. The apple needs a good balance of nutrients to develop well including; calcium, potassium and nitrogen, boron, copper, manganese and zinc. As a food source for humans and other animals, the apple is very low in fat, cholesterol and sodium. It is a good source of Dietary Fiber and Vitamin C. A large portion of the calories in this food come from sugars. Most of the nutrients that eventually end up in an apple are taken from the soil, water, and air (macrosystem) the previous year (chronosystem) and retained within the tree as reserves in tree buds, bark and roots (mesosystem). These are then remobilized the following spring to fuel leaf growth, flower bloom, and ultimately, the apple. Along the way, there are many interactions with bacteria, fungi, insects, and manmade interventions and contaminants (pesicides, fungacides, arsenic) that can change the apple in obvious and subtle ways. All of these interactions can be more closely examined and represented in the mesosystem layer of this model. MESOSYSTEM : PERSON, C OMMUNITY AND CULTURE The mesosystem layer in ecological systems theory describes the immediate llinkages and contextual relationship between the central player, be it a food item, or a child, and the specific and immediate forces that impact, influence, and shape the development of this central figure. One aspect of the mesosystem is how the apple interacts within the human body. The apple and other foods we eat each day directly effects our bodies physiological growth, maintains all processes of our bodies, and supplies the energy to maintain body temperature and activity. Once eaten, the apple is mechanically and chemically broken down by enzymes in the mouth, and then travels down the esophagus to the stomach. It is the stomach that breaks down any proteins. The small intestine releases more enzymes to break down fats before the supplemental nutrition is absorbed in to the blood and lymph so that it can travel to the bones, muscles, eyes, and all other parts of the body that need nutrients. Our guts are complex collaborative systems, signaling and responding to what we eat in a variety of ways. This system also includes complex interactions between bacteria that digest our food and hormones, enzymes, and chemical messengers that signal hunger, fullness (satiety), sleep, mood states and mediate immune responses to disease that are just beginning to be explored. In addition to food satisfying our appetite and other physiological needs,food and beverages bring people together. Food is one of the greatest community builders. Growing food, cooking food, and eating food are all community and leisure activities. Food is also the foundation of human culture. All cultures around the world have food traditions, rituals and identity. In fact, the word “culture” originates from the Latin word “cultura,” which in translation means “cultivation.” We cultivate our food from the soil. We cultivate our ideas and methods of preparing the food by passing from generation to generation. Furthermore, based on the culture within we are raised; there will be specific foods we are “acculturated” to enjoy (Katz, 2012). EXOSYSTEM: FOOD SYSTEMS & POLICIES Our apple serves as food or nourishment, one way or another. Either it falls, and remains on the ground re-integrating into the soil, or it is harvested by animal life as nourishment. Fruit and vegetable plants (currently, mostly corn and soy) feed our beef, pork, chicken, fish which are processed into fillets, steaks, hamburger at a meat processing facility. Animal excrement is also used to “feed” the soil. So, in a current, typical food system cycle, our fruit, vegetables, or meat are ideally chilled or frozen right after processing to the proper temperature , and are stored until sold to wholesale or retail customers when the food is transported from the chilled aggregating facility to retail stores, institutions like schools, hospitals, nursing homes and at restaurants or individual homes. To keep our chilled or frozen foods safe, transport to all of these destinations will require either short distances or a temperature controlled environment. Similarly, our grains, fruits and vegetables require processing, aggregations, storing and transporting to interim (retail) or final (restaurants , institutions, household) destinations. This is one example of the exosystem layer; understanding and examining more “upstream” interactions between the food and humans in our model. Largely as a result of the industrialization of farming, our current food delivery system requires a great deal of regulation to keep our foods fresh and relatively free of contaminants. Our modern farm-to-table food system is complex. Fossil fuels are currently used (with few exceptions such as Amish communities) at every step in our food system. Calculating the carbon footprint of a typical crop of Iowa corn or soy from farm to table is complex, and often, our crops end up across the globe. Think how different this is from our family farm heritage where the fruit and vegetables were plucked from the back yard and either eaten directly or preserved for the winter. The culture, taste, politics, and economics between these two food system cycles are very different. What is currently of great interest at local and regional levels is an examination of how we can rebuild some part of our local food infrastructure in order to enhance both community health and economic development. Of course, here there are obvious solutions; buying fresh and buying local. Growing, harvesting, delivering and consuming foods locally is good for us economically; local dollars, local jobs, Local food consumption has great potential for reducing carbon footprints, but this potential requires understanding the many inputs. From fertilizers to Styrofoam take-out boxes and wasted food. MACROSYSTEM LENS : EARTH & S OIL The purpose of the macrosystem level of our ecological model is to examine the larger lens implications of our microsystem (apple). Modern agricultural has allowed societies to control the food supply and also develop a food surplus that supports a larger population. At the same time, modern agricultural practices have radically manipulated the environment. As the world’s population increases, the demand for food increases. As past civilizations made food decisions that shape the world we live in today, the path of our future depends on the today’s choices (Smith, 2010). How much of the Earth do we really use to produce food? Using the apple to represent the Earth, ¾ of the planet is covered in ocean where food cannot be grown. The remaining ¼ of the apple represents land masses but much of this land is mountains, deserts and ice that cannot produce food. Of the 1/8 of the apple that is left over, most is used for cities, buildings, roads and parking lots that the soil is so depleted that food will not grow. With the remaining 1/32 of the apple representing the earth’s farmable top soil of an average depth of 5 ft, how wisely are we using this soil available to supply the nutrients for the development of plant and animal food we eat (American Farmland Trust )? Are we protecting and replenishing this crucial resource or are we “managing” crops in order to maximize profits and the availability of cheap foodstuffs? CHRONOSYSTEM LENS: TIME AND POPULATION G ROWTH The chronosystem, or examination of how time impacts our apple, or the humans that eat that eat the apple, or the soil in which the apple tree grows, can help us to gain perspective; apple time, human time, and earth time, still need to be understood through our human capacity to understand the context. In 2050, the world population is projected to be at 9.2 billion. With this dramatic increase in the last 100 years, there has also been a migration of people from rural areas to cities. In 2008, there was a pivotal point where more of the world’s population not lives in cities than in rural areas (Smith, 2010). This shift has an environmental impact as well as impact on how urban individuals access food. For the first time in human history, the majority of humans have no knowledge on how to cloth, feed, or perform the most basic biological functions. Instead we increasing rely on globalized companies, such as Hyvee, Aldi, and Walmart, to supply us with our very basic biological needs (Smith, 2010). The companies play an important role as they reach out around the world to obtain food and services and route them on a tightly scheduled supply chain to deliver them to us, the urban consumer as cheaply and efficiently as possible (Smith, 2010). SUMMARY Our guts are complex collaborative systems. Our apple grows in another complex, collaborative system; the soil. Finally, the production, processing and distribution of our foodstuffs (or getting the food from the farm to your table) is a complex, competitive/collaborative endeavor. We need to begin to understand and appreciate how these systems operate and interact in our lives in order to inform our own personal understanding and development which may then help us to be an agent of change for others. Even these cursory examinations of some of these interactions lead us too easily toward backing away from the complexity. The “big picture” appears too big and too broad to comprehend, let alone “fix” or “teach” to others. A systems paradigm is needed to allow us a way to deconstruct and then reconstruct our food system. We can ask a specific set of questions or examine an issue such as racial disparities in childhood obesity through this ecological model and figure out what factors (at various points in time) may best protect, promote, or put us at risk for poorer outcomes of health and wellbeing. Yet, peel back the mask of these food permutations, you will still find evidence of the cultural norms and battles that reveal us. For example, have you noticed that friendly, folksy, and collaborative cooking shows are being rapidly pushed out to make way for competitive, winner-take-all cooking competitions complete with snarky judges, immunity, and substantial prizes. Is this a conscious or unconscious devolution? I’m sure it is all about gaining an audience and selling advertising, but what about the big picture? How do we, as educators and professionals, make sense of the media frenzy around food and obesity? Why is this topic so important and how might it affect us, our profession, our students? There is, an ongoing and rich discussion that is taking place on University of Northern Iowa’s campus now and in the near future with community “Blue Zones” projects, as well as UNI’s American Democracy Project’s focus next year on “The American Way of Eating”. Let’s engage. This larger lens understanding of food in relation to human health, development and learning can inform, and increase the potential for change within the system. Let’ allow ourselves and encourage others to pay more attention to the complexity of food….or at least to the choices we make regarding the food that is around us and see how shifts in one part of the system may reverberate to other levels. If every family made a commitment to devoted 10 cents of every food dollar to local foods, how might this affect our communities; our farmers, restaurants, businesses? References Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, Vol 32(7), 513-531. Ecological systems theory.Bronfenbrenner, UrieVasta, Ross (Ed), (1992). Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues. , (pp. 187-249). London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, , 285 pp. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. Bronfenbrenner, Urie; Morris, Pamela A. Lerner, Richard M. (Ed); Damon, William (Ed), (2006). Handbook of child psychology (6th ed.): Vol 1, Theoretical models of hu man development. , (pp. 793-828). Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc, xx, 1063 pp.