THE EFFECTIVENESS OF VOTE CENTERS AND THEIR IMPLEMENTATION IN INDIANA

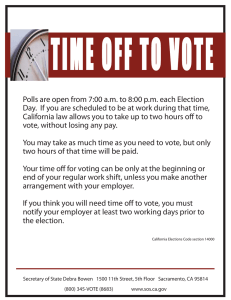

advertisement