Document 10868979

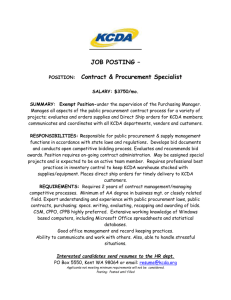

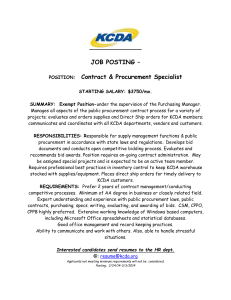

advertisement