71 by Isaz Miyazaki Center for

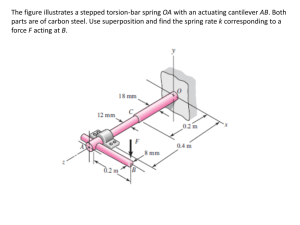

advertisement