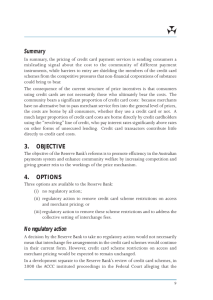

Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited Reserve Bank of Australia

advertisement