Female Leadership and Firm Profitability Summary No. 3

advertisement

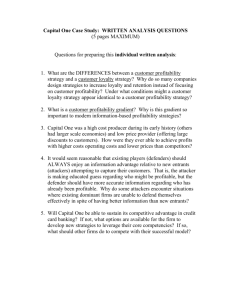

No. 3 24.9.2007 Female Leadership and Firm Profitability Annu Kotiranta – Anne Kovalainen – Petri Rouvinen Summary Less than a tenth of the CEOs of Finnish firms and less than a fourth of the corporate board members are women. From a social standpoint more women are desired in top management, but should firms’ owners and those represent­ ing their business interests be concerned with women’s role in top management? Since hard facts have been in short supply, we seek to an­ swer the question by applying scientific research methods. possible (and even likely) that, due to the more harsh selection process, female business leaders constitute a more exclusive – and thus a more competent – group than their male peers. Female leadership may also be associated with a firm’s overall cultural diversity and multidimensionality as well as good governance and management practices. Our findings suggest that a firm may gain a competitive advantage over its peers by identi­ fying and eliminating the obstacles to women’s advancement to top management. While there is on average a positive correlation with female leadership and profitability, a too straightforward and wrong conclusion would be that the current male leaders should be replaced by women and that this would improve firms’ profitability. The focus should rather be on the numerous and often difficult-to-observe mechanisms and net­ works that favour men or hinder women from climbing the executive ladder. Gender-neutral career opportunities are – besides being “fair” – also in the best interest of companies. Our results indicate that a company led by a female CEO is on average slightly more than a percentage point – in practice about ten per cent – more profitable than a corresponding company led by a male CEO. This observation holds even after taking into account size differences and a number other factors possibly affecting profit­ ability. The share of female board members also has a similar positive impact. These findings are significant and important not only from a statis­ tical and research perspective but also from a business standpoint. But why does female leadership seem to con­ tribute to a company’s bottom line? Several suggestions are consistent with our findings, even though – due to data constraints – we are unable to evaluate their respective merits: Women may be better leaders than men. Or it is If and when Finland seeks to increase the share of women in top management, these endeavours should not be hindered because of concerns about private firms’ profitability – quite the contrary, in fact. Should firms’ owners be interested in women’s position? Less than a tenth of Finnish firms’ CEOs are women Finns can boast about high gender equality – except when it comes to business leadership. Less than a tenth of firms’ CEOs and chairmen of the board are women; less than a fourth of firms’ board members are women.1 The corresponding shares of large corporations are even lower. According to a worn out Finnish proverb, “War does not long for one man”. But would business leadership be in need of additional women? From a social standpoint the answer is obviously “yes”: it is right and fair that women and men have equal opportunities for success in business. The present gender imbalance in top management suggests, however, otherwise. Another, and more challenging, question can be raised: is it worthwhile for business owners and those representing their interests to be concerned about women’s role in top management? From a corporate social responsibility perspective the answer is again “yes”. But how does the issue stand in light of cold accounting figures? Many politicians have stated that Finland cannot afford not to utilize women’s knowledge in listed companies’ board of directors. Vladimír Špidla, EU Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs & Equal Opportunities, has claimed that selecting women in leadership positions is profitable for businesses.2 Despite political belief, the stances of both research and business communities have been more reserved due to the scarcity of hard facts on the matter. A few dozen studies can be found in international academic literature (see Box 1) focusing on the connection between female leadership and the financial success of a business. The research topic is not an easy one, and the findings are contradictory. Often small and skewed data sets limit the creditability of the studies. Moreover, the shares of women in top executive and management positions are often so small that even in samples of thousands of firms there might be only a few female leaders. The previous literature nevertheless indicates that there might be a positive correlation between female leadership and financial success. We conduct statistical and econometric analysis to determine, whether Finnish firms with female leadership are more profitable than other firms. In this paper we report our key findings. The details of our analysis are reported in the forthcoming research publications.7 Box 1 Some observations of recent studies on the relationship between female leadership and business performance Richard et al. (2006) studied the impact of the per­ sonnel’s cultural diversity (in addition to gender also ethnic background) and organizational structure on firm performance and profitability in the US banking sector. According to the results the share of female workers is not connected with firm profitability. In topheavy and hierarchical organizations (high number of managers as a proportion of total employees) a positive relationship can nevertheless be found; in mature and rigid organizations the relationship may even be negative.3 Rose (2007) studied the relationship between the gender structure of corporate boards and business performance. According to the results the gender diversity of the board does not affect performance.4 Smith et al. (2006) studied the relationship between the gender structure of Danish firms’ management and business performance. According to the results the share of female board members and female CEOs are positively correlated with firm profitablity.5 Wolfers (2006) investigated the possible discrimina­ tion against women as CEOs. According to the results the expected earnings of companies led by female CEOs are not systematically underestimated by stock market analysts.6 Female leadership pays off It should be emphasized that the aim of our study is not to further “the female cause”. The results are based on accurate and comprehensive data and appropriate research methods. The research question has been approached as objectively as possible. Our target population – compiled by Statistics Finland – comprises of Finnish limited companies employing at least 10 persons in 2003. The employed sample covers 91 per cent of the target population.8 Our sample is even internationally the most extensive and representative firm-level data used in gender research. Of the sample businesses 7.6 per cent have a female CEO and 7.1 per cent have a female chairman of the board. On average 22.3 per cent of the board members are female (see Fig. 1). Because the gender of the board’s chairman does not, according to our empirical analysis, have a significant effect, we will focus on female CEOs and on the share of women on corporate boards. Thus, when comparing direct (unconditional) means, firms led by women are 2–3 percentage points – from slightly over 10 to well over 20 per cent – more profitable than businesses led by men. This in itself is not, however, a solid basis for drawing conclusions, as firms led by men and women also differ in several other respects: – In all of the examined dimensions firms with female leadership have less export activity, they are less likely to be a part of a business group, and they are less capital intensive. We also observe statistically sig- Figure 1 Should firms’ owners and persons representing their interests be concerned with women’s role in top management? Shares of Female CEOs and Board Members (limited liability companies employing at least 10 persons and operating in Finland in 2003) Share of firms with female CEOs 7.6% Several indicators of business profitability were examined in our study: return on assets (the primary indicator), return on investments and the operating margin.9 Is female leadership correlated with financial success? Our findings suggests that this is indeed the case. Female CEO Male CEO A simple comparison of respective (unconditional) means reveals that businesses managed by women and men are different in several respects (see Fig. 2): – The average profitability of firms in the sample is 12.3 per cent. The average profitability of firms with a female CEO is 14.0 per cent. The difference (1.8 percentage points) with a male CEOs firms’ average of 12.2 per cent is statistically very significant (1 per cent level). – The average profitability of companies having at least half of female board members is 14.7 per cent. The difference (3.1 percentage points) with respect to other firms’ 11.5 per cent is statistically very significant (1 per cent level). Average share of female corporate board members 22.3% Females Men Sources: Statistics Finland, Asiakastieto Oy, Etlatieto Oy, and calcula­ tions by the authors. Female- and male-led companies differ from each other in many respects When comparing direct (unconditional) means, firms led by women are 10–20 per cent more profitable than businesses led by men Figure 2 Profitability Differences between Companies Led by Women and Men (adjusted return on assets; limited liability companies employing at least 10 persons and operating in Finland in 2003) Sources: Statistics Finland, Asiakastieto Oy, Etlatieto Oy, and calculations by the authors. nificant differences in a number of other variables, although their directions vary according to the leadership dimension considered. – Furthermore, female leadership varies by industry and region as well as by firm size and age. For example, female leadership is most common in education, health, Figure 3 Shares of Firms with Female CEOs in Different Sectors (limited liability companies employing at least 10 persons and operating in Finland in 2003) Sources: Statistics Finland, Asiakastieto Oy, Etlatieto Oy, and calculations by the authors. and social services as well as in hotels and restaurants (see Fig. 3). Female leadership is more common in smaller firms.10 In order to isolate the effect of female leadership, a multi-dimensional regression analysis was employed to control for other factors possibly affecting firm profitability (see Box 2). After controlling for the other factors, the positive conditional correlation between female leadership and profitability is expectedly somewhat weaker than the unconditional one (see Fig. 4).12 It nevertheless remains positive as well as statistically and qualitatively significant: – A firm with a female CEO is slightly more than a percentage point – in practice about 10 per cent – more profitable than an otherwise similar firm with a male CEO. – The effect of the share of female board members is similar; a firm with a genderbalanced board is on average about 10 per cent more profitable than a similar firm with an all-male board. Examining female CEOs and female board member shares within the same model shows that they have their own independent effects on profitability.13 Our findings show that female leadership and a firm’s profitability have a positive correlation that is not explained by observable firm-specific and sector-specific factors. It should be emphasized, however, that what we uncover is indeed a correlation; it is not a causal relationship from female leadership to firm profitability or vice versa. Due to data limitations we are also forced to be somewhat vague on the individual- and (unobserved) firm-specific factors that might drive our findings. These issues are among the most important avenues for further research. Releasing women from the aquarium The observed positive and statistically significant correlation between female leadership and profitability is an interesting and important finding for both the research and business communities. Unfortunately we cannot shed light on causal relationships underlying our findings. Data permitting, one should consider a wide range of personal and socio-cultural factors. Even so, several conclusions can be drawn. The possible explanations for the correlation fall into one or more of the following four categories: Box 2 Isolating the profitablility impact of gender In our models the dependent variable is profitability.11 Of the independent variables, the most interesting ones are the gender of the CEO and the share of women in the corporate board. Other independent variables were: - The age of the firm’s CEO; - The size of the board, the average age of the board members, the age difference between the young est and the oldest board member (a proxy for heterogeneity); - The CEO is also the chairman of the board; - The firm’s export activity, its capital intensity, its foreign ownership, its group relationship, its credit – rating, its auditor’s statement (unconditionally approved), its gearing ratio; as well as The firm’s industry, its geographical location (the headquarters), its size (in terms of personnel) and its age. Our model controls for all of the above-mentioned factors. In other words, our findings are not attribut­ able, for example, to industry or size differences, but rather the findings drawn from the regression analysis are conditional on all of the above factors, i.e., the effects are already accounted for in the remaining partial correlation between female leadership and firm profitability. Female leadership and firm profitability have a positive correlation even after controlling for other factors Figure 4 ”Pure” Impact of Female Leadership on Firm Profitability (limited liability companies employing at least 10 persons and operating in Finland in 2003)14 Profitability impact after taking into account other factors (see Box 2): Profitability gap of female CEO vs. male CEO Analysed separately Profitability gap attributable to share of female board members Female CEO Both analysed in the same model and Share of female board members Sources: Statistics Finland, Asiakastieto Oy, Etlatieto Oy, and calculations by the authors. *** Statistically extremely significant (1% level). ** Statistically very significant (5% level). Interpretation of board share coefficients: completely female vs. male board. Women CEOs (possibly) lower wages do not explain the observed correlation – Generally speaking women may be better leaders than men (adjusted for the executive compensations of the respective groups). – Upon advancing towards top management, women may be faced with more harsh selection (due to, e.g., sex discrimination) making them a more exclusive and thus on average better group as compared to men in top management. – Women may seek management positions in, or may be selected to lead, more profitable businesses. – Both female leadership and profitability could be connected to some third (unobserved) factor. Are women generally speaking better leaders? In case of the two first categories above, women cause better business performance via their qualities and actions; in case of the third category, the causality runs from better performance to female leadership; in case of the fourth category, unobserved factor(s) mislead research efforts. Are women generally speaking better leaders? Although our findings are consistent with the argument that women are better leaders than men, they do not actually prove it. Indications that women’s leadership style might well be better suited for modern day requirements have been found, e.g., in psychological literature. In a study resembling ours,15 the causality issue was studied (by employing instrumental variable methods). The observation was that in Denmark female leadership seems to be causing a firm’s better profitability. Because our data did not include information on CEOs’ wages, we could not explictly study their effect. Information gathered from other sources and our preliminary calculations suggest, however, that the (possibly) lower wages of female CEOs explain only a minor part of the observed correlation. Are female leaders more exclusive and thus on average better group than corresponding men? Provided that the leadership qualities of men and women are somewhat similar and those best suited for business management are Box 3 Concepts related to women’s advancement in working life Glass ceiling. The possibilities of women to move up in an organization above a certain hierarchical level are hindered by sex discrimination. “Glass” refers to the notion that this is an unofficial and difficult-to-observe phenomenon. “Ceiling” refers to the idea that climbing up the corporate ladder is prevented. The glass ceiling does not refer to discriminatory practices that are of­ ficial rules (such as the fact that until recently women could not join the Finnish army) or other barriers to promotion (for example, lack of necessary skills or experience). in fact selected, the present imbalance between genders in business management indicates the existence of a “glass ceiling” (see Box 3) obstructing the advancement of women. Thus, because women go through a tighter “screening”, the average leadership abilities of women who have ended up in top management may be better than those of the corresponding men. The observations of our study are consistent with this positive selection of women, although they do not, as such, prove it. Do women end up in more profitable firms? Causality from profitability to female leadership is not among the most plausible explanations for the observed correlation, even if it is nevertheless a possible one. If it were true in the broad sense, female leaders would, more often than corresponding men, seek to be employed by more profitable firms (or ones becoming so due to exogenous reasons), or more profitable firms would be more eager to employ women leaders than otherwise similar firms that are (exogenously) less profitable. Does some third factor account for both female leadership and firm profitability? Unob­served factors of female leaders and their firms in-part explain the observed correlation. As discussed in prior literature, female leadership might be more broadly connected to the cultural diversity and multi-dimensionality of a business. Indeed, our further (preliminary) analysis suggests that corporate boards with a Glass wall. Their gender might limit women’s possibili­ ties to move within the organization from one job or business division to another. Glass door. Owing to their gender, women have worse possibilities to get their foot in the door of an organization; in the recruitment stage, for example, they might be less likely to be asked for interviews than men with similar qualifications. balanced gender composition might have the highest correlation with a firm’s profitability (see Box 4). The connection between a firm’s multi-dimensionality and its profitability is a complex one: it seems likely that only a sufficiently tolerant and flexible organization is able to utilize the competitive advantage brought about by multidimensionality. If an organization is rigid, it is unable to question old ideas and welcome new ones stemming from heterogeneity. Are female leaders a more exclusive and thus on average better group... Female leadership may also be connected to good corporate governance and management practices. Observing women also at the top of the corporate hierarchy may indicate that advancement and appointments in these organizations are based on competence and merits, not on traditions and established conventions. Furthermore, it seems only logical that the compositions of top management and corporate boards should reflect the diversity in firms’ employment and customer bases also in terms of gender. It may be that several factors, from so-called natural differences in values and preferences of men and women all the way to educational segregation, lead to some sort of – although certainly smaller than at present – gender imbalance in business leadership. If this is indeed the case, the ultimate objective should depart from a perfect gender balance. ... or do women end up in more profitable firms? A gender balanced board may maximize profitability Box 4 Is there an optimal gender composition of a corporate board? The findings discussed in the text are based on a linear modelling of the women’s share in corporate boards: the adjacent graph uses the same model except that the women’s share is modelled nonlinearly, after which we have used a simulation to visualize the relationship in question (naturally taking into consideration all other factors mentioned in Box 2). In the graph the vertical axis is profitability and the horizontal axis is the women’s share. As can be seen, the positive partial correlation is the strongest with intermediate values of the women’s share, i.e., with reasonably gender-balanced corporate boards. The linear effect nevertheless remains within the confidence interval of the nonlinear effect, and thus the simpler linear model is employed upon deriving the core findings reported in the text.16 Figure 5 Impact of a Corporate Board’s Gender Distribution on Firm Profitability Note: The vertical lines depict the 90 per cent confidence interval – the lines break at the mean estimate. Sources: Statistics Finland, Asiakastieto Oy, Etlatieto Oy, and calculations by the authors.17 Women to the top! Business decisions do not respect the logic of democracy or altruistic striving for gender equality. Business owners and those representing their interests are of course concerned about the matter in the name of corporate social responsibility. Gender equality might be listed among the corporate values, but ultimately only its connection to financial success ensures their interest. Our findings reveal a positive and significant correlation between female leadership and firm profitability. Even if we do not prove causality, our findings have several important implications. Our findings suggest that a firm may gain a competitive advantage over its peers by identifying and eliminating the obstacles to women’s advancement to top management. While there is on average a positive correlation between female leadership and profitability, a too straightforward and wrong conclusion would be that the current male leaders should be replaced by women and that this would improve firms’ profitability. The focus should rather be on the numerous and often difficultto-observe mechanisms and networks that favour men or hinder women from climbing the executive ladder. Gender-neutral career opportunities are – besides being fair – also in the best interest of companies. Helena Terho, Vice President responsible for Competence Development at Kone Oyj, recently directed attention18 to the glass ceiling (see Box 3) preventing women rising to top management and to glass doors and glass walls, i.e., to the phenomenon that even initially women have a harder time getting job interviews and that when in a post they move more seldom from one task or line of business to another, which in turn is a requirement for rising to top management. The safeguarding of equal career opportunities for female and male executives is in the interest also of companies. If the skills of women are systematically underestimated in stages following middle-management and preceding top management, they will not have opportunities for success in later stages possibly based on fully objective criteria and merits. our apologies. Clearly one should not be evaluated as a member of a group, but rather as an individual. Other personal factors, besides gender, are more important in determining one’s leadership ability. Our study uncovers a few key results; along with our basic answers a broad group of new questions arises, of which we already mentioned a few. We do indeed hope that our observations lead to additional research. If and when Finland seeks to increase the share of women in top management, these endeavours should not be hindered because of concerns about private firms’ profitability – quite the contrary, in fact. It can be said that the present modest share of women at the top of business life is not only a national discredit, but also a factor lowering our mutual (also men’s!) prosperity and well-being. Also in Finland promoting female leadership by legislative means has been discussed. Norway has already proceeded with this: according to the gender quota law of 2004 – which in practise concerns some 500 companies – boards must have 33–50 per cent of members of both sexes. In Finland a corresponding law would require changes in 98 per cent of listed companies.19 We are not necessarily supporting female quotas or processes, although they could be called for in the transitional period, during which the role of women in business life would normalize. In any case active measures are required to ensure the equal opportunities for success by women and men, but the means should rather be influencing the public opinion and corporate culture. Our study is inevitably stereotypical and omits some of recent debate on the matter – for which A firm may gain a competitive advantage by eliminating obstacles to women’s advancement... ... and these endeavours should not be hindered by related profitability concerns Annu Kotiranta studies economics at the University of Helsinki and worked as an intern at ETLA, The Research Institute of the Finnish Economy, in 2006–2007. Anne Kovalainen (Ph.D.) is a professor of business knowledge and entrepreneurship at Turku School of Economics. She has worked as a professor of women’s studies and entrepreneurship at the Swedish School of Economics and Business Administration (Helsinki). She has been a visiting professor at Stanford University (USA) and the London School of Economics (UK). Petri Rouvinen (Ph.D.) works as Research Director at ETLA, The Research Institute of the Finnish Economy, and its subsidiary Etlatieto Oy. Sources King, G., Tomz, M. & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the Most of Statistical Analyses: Improving Interpretation and Presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44(2), 347–361. Rose, C. (2007). Does Female Board Representation Influence Firm Performance? The Danish Evidence. Corporate Govern­ ance: An International Review, 15(2), 404–413. Kovalainen, A., Vanhala, S. & Mélart, L. (2007). Women and Eco­ nomic Decision Making at Private Companies. Forthcoming. Smith, N., Smith, V. & Verner, M. (2006). Do Women in Top Management Affect Firm Performance? A Panel Study of 2 500 Danish Firms. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 55(7), 569–593. Richard, O. C., Ford, D. & Ismail, K. (2006). Exploring the Per­ formance Effects of Visible Attribute Diversity: The Moderating Role of Span of Control and Organizational Life Cycle. Inter­ national Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(12), 2091–2109. Wolfers, J. (2006). Diagnosing Discrimination: Stock Returns and CEO Gender. Journal of the European Economic Associa­ tion, 4(2/3), 531–541. Tomz, M., Wittenberg, J. & King, G. (2001). CLARIFY: Software for Interpreting and Presenting Statistical Results. (Version 2.1). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. 10 Endnotes By the term “board” we refer to the board of directors (or board of supervisors, supervisory board), which is a group of people who monitor the interests of shareholders and officially administer a company. We do not refer to the board of executives (or executive board, board of manage­ ment, managing board, management board), which is a group of people responsible for the everyday management and administration of a company and carrying plans into practical effect and is accountable to the board of direc­ tors (or the supervisory board). It is worthwhile to note, however, that the composition, role and importance of the board of directors (or the supervisory board) in terms of the actual leading of the company vary from one country and corporate governance system to another. 1 2 MTV.fi in 7 October 2006. The study was carried out by using a questionnaire completed by 79 firms in banking. The response rate was 16%. 3 on the best indicator or measurement practice. In this analy­ sis profitability refers to the adjusted (winsored ±2,5 %) Re­ turn on Assets (ROA), which we regard as the best indicator and which gives results that are fairly uniform with the other alternatives. The average sizes of firms with male and female CEOs are, respectively, 71 and 56 employees. The average size of firms with male-dominated boards (over half ) is over 80 employees while the corresponding figure for firms with female-dominated boards (at least half ) is under 30 employ­ ees. 10 A total of 24 different regressions (in addition to 6 de­ pendent profitability variables and basic independent vari­ ables, there were 4 different alternatives for female variables – 3 indicators separately and all three together; heteroske­ dasticity consistent least squares method) including 44 or 46 dependent variables; complete results are reported in our research publications. 11 Sector-specific and other observed differences between firms thus explain part of the relationship between female leadership and profitability. 4 The data cover slightly over 100 listed companies during 1998–2001. The indicator of stock market success was Tob­ in’s Q. 12 The data covers 2,500 companies in 1993–2001. Espe­ cially highly educated female CEOs improved the profitabil­ ity of the company. In the study the causality was assessed with the help of an instrumental variable method. 13 5 The indicators used are expected and realized returns from holding the stock. The sample consists of 1,500 firms in 1992–1994. Of the data’s 4,239 CEOs, 64 are women. Accord­ ing to Wolfers the results may tell more about the weakness of the data than about the market’s underestimation of the profit-making ability of female CEOs. The impact of both a female CEO and the share of fe­ male board members remain similar (albeit slightly weaker), even though they are included in the same model; they are related to one another, but they have separate and inde­ pendent impacts on firm profitability. 6 Forthcoming in the ETLA Discussion Papers Series as well as the Turku School of Economics Discussion and Work­ ing Papers Series. 7 Note: When assessing the share of female board mem­ bers the comparison is between completely female and completely male boards. See also Box 4. 14 Smith et al. (2006). 15 It is good to note that most of our statistical data obser­ vations are on the rising portion of the curve. 16 Simulated with Stata 9.2 and Clarify 2.1 (King et al. 2000; Tomz et al. 2001). 17 The supplementary financial statement and other in­ formation have been obtained from Asiakastieto Oy. The sample (12,738 firms) used in our analysis covers over 90 per cent of the target population as defined by Statistics Finland. 8 Strictly speaking there were six indicators used, since the three profitability indicators mentioned were as­ sessed as such and in versions where extreme values were smoothed; this is because there is not a complete consensus On May 10, 2007 (on the occasion of publishing Dr. Anna Kortelainen’s EVA Report ”Leading stars – Finland’s first women leaders”). 18 9 Kovalainen, Vanhala and Mélart 2007; situation in the year 2003. 19 11 Finnish Business and Policy Forum EVA Finnish Business and Policy Forum EVA is a pro-market think-tank financed by the Finnish business community. It is also a forum for forward-looking discussion for Finnish business leaders. EVA’s task is to identify and evaluate trends that are important for Finnish companies and the society as a whole. EVA aims to provide current information on prevailing trends as well as bring fresh ideas to public debate. EVA publishes reports, organises debates and publishes policy proposals. This EVA Analysis is a part of the “Women to the Top!” -project, which EVA launched together with the Palmenia Centre for Continuing Education. The project is funded by the European Social Fund (ESF). The authors of this analysis are not affiliated with EVA. Further information: www.eva.fi Published by the Finnish Business and Policy Forum, EVA Analysis is a regular se­ ries evaluating policy issues and offering proposals for reform. The views expressed in EVA Analysis do not necessarily reflect the views of the EVA. Additional copies of EVA Analysis can be downloaded from EVA website www.eva.fi. To order print copies of EVA Analysis, send email to address analyysit@eva.fi, or call +358-9-6869 2035. 12