Fire the Caterer: A Test of Catering Theory ... Payout Policy

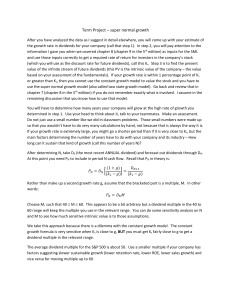

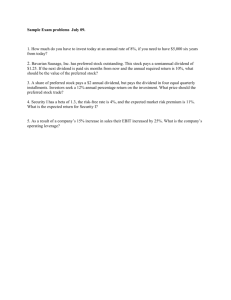

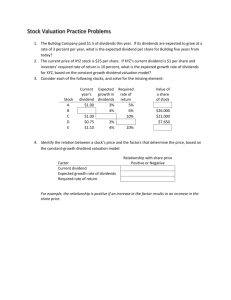

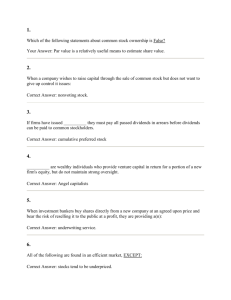

advertisement