Reconciliation and development of identity after the Second World War:

advertisement

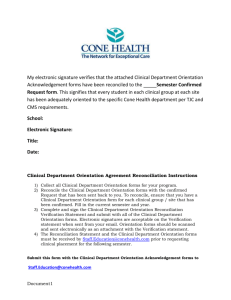

Reconciliation and development of identity after the Second World War: A comparison between Germany and Japan National and regional identities in an age of globalization Honors Program: Discourses on Europe Tilburg University Word-count: 6306 May 2015 Course supervisor: Prof. Dr. A.J.A Bijsterveld Students: Tom van de Wijgert ANR: 298038 Edwin Alblas ANR: 295616 1 Research question: To what extent have Germany and Japan reconciled with their wartime histories, and how has this influenced their role in the region, respectively Central Europe and East Asia. Abstract: The Second World War is generally regarded as one of the most horrible events in modern history. In just five years millions of people got killed, in combat, in camps or due to the dreadful living conditions. Ultimately the allied forces won the war and the aggressors, Germany and Japan surrendered. In this paper, an answer has been sought to the question To what extent have Germany and Japan reconciled with their wartime histories, and how has this influenced their role in the region, respectively Central Europe and East Asia. The short answer to this question is that Germany has, to greater extent than Japan, been able to reconcile with its past and create strong ties with its regional partners. Realizing that the question is too extensive and complicated to find an inclusive answer for in this paper, the main goal is to stress the impact the Second World War has had on today's day and age and, more specifically, the ties in two specific regions namely Central Europe and East Asia. Key terms: Second World War, reconciliation, regionalism, shame versus guilt, post-war. 2 Introduction The Second World War is generally regarded as one of the most horrible events in modern history. In just five years millions of people got killed, in combat, in camps or due to the dreadful living conditions. Ultimately the allied forces won the war and the aggressors, Germany and Japan surrendered. Only long after 1945 the world started to truly grasp the scope of atrocities that had been committed during the War and, as will be discussed in this paper, it would take an even greater amount of time for the horrors to be forgiven, or even forgotten. Now, almost seventy years after the War, it might be a good opportunity to reflect upon the importance of the War for the world of today. Do the different parties still hold grudges towards each other, or is the Second World War merely a memory of what has long passed? We can already state that, despite the devastated state the countries were in when the War had just ended, both Germany and Japan have evolved to incredibly wealthy and economically stable countries. Germany and Japan rank respectively as the fourth and third largest economies in the world according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2014). Rather surprising it is to notice that the two ‘losing’ countries of the Second World War so rapidly rose from their ashes and evolved into the major world players they are today. This will be examined in this paper. The research question is as follows: To what extent have Germany and Japan reconciled with their wartime histories, and how has this influenced their role in the region, respectively Central Europe and East Asia. This paper has been divided into three parts. In the first part, the case of Germany will be examined in which the post War situation will be examined, as well as the the development of identity after the War and the implications of this for its place in the region. In the second part, the same structure will be used but then with respect to Japan. In the third part, the analysis, similarities and differences will be sought concerning the ways in which Germany and Japan have reconciled with their past. 3 1. Germany Image: Der Warschauer Kniefall, Warschau, Poland, 1970 (Der Spiegel) 1.1 Post-Second World War situation In this chapter, the post-Second World War situation in Germany will be examined. The question that will play a central role is as follows: "What the historical background with which Germany had to cope?" As will become clear, the influence of the allied forces and the division of Germany have had a great impact on the process of reconciliation (Conrad, 2003). This brief historical perspective will serve as a framework for the analysis of Germany’s development of identity after the Second World War, which will be discussed in the second paragraph. In the third paragraph, it will be discussed how Germany has tried to reconcile with the war crimes committed under the Nazi-regime has influenced its regional position. On the 8th of May, 1945, Germany officially surrendered to the allied forces. After five years of war, the European continent was absolutely devastated. Over the years, the Germans slowly began to realize the atrocities they had committed during the War, after which the process of reconciliation would start. At the Potsdam Conference of 1945, the allied forces divided Germany into four military zones: French, British, American and Soviet (Overy & Turner, 4 1991). Next to being occupied by these four different countries, Germany also had to give up much of its former territory. Not only did it lose the territory which was annexed or conquered during the Second World War, Germany also had to abstain from eastern parts such as Prussia, Pomeriana and Silesia, which were partly handed over to Poland and the USSR. These areas used to be German and as a result roughly 12.4 million Germans that were still living in these areas suddenly were no longer German. These Germans were expelled from their homes and had to move to one of the four military zones. Unfortunately, millions of them died due to the harsh living conditions of that time (Orzoff, 2014). On 23 May 1949, the three zones occupied by the French, British and Americans merged to form the Bundesrepublik Deutschland (FRG). In the same year the Soviet part became the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR). The division of Germany was a fact. Besides these two republics there were a few exceptions, namely the Saar protectorate, the Ruhr area and Berlin. Both the Saar protectorate and the Ruhr area were important parts of Germany’s former industry specialized in raw materials such as coal and steel, necessary components to constitute an army. The Saar area was under a protectorate of France until it was incorporated in the FRG in 1956. The Ruhr area was under control of the International Authority of the Ruhr, constituted to keep a close watch on the extraction of coal and steel. The authority was disestablished in 1952 when the activities of the authorities were moved to the European Coal and Steel Community, which will be discussed in further detail later on. Just like Germany itself was divided in East and West, the old capital Berlin became divided. The Western part formed an enclave in the DDR which was under Western control until 1990 (Overy & Turner, 1991). It seems most difficult to analyze the process of reconciliation with the past in such a divided country, even in a divided world. In the post-War period, most of the world became divided in East (communist) and West (capitalist). The interpretation of wartime atrocities in Germany was greatly influenced by this division during the Cold War. However, territorial loss and division were not the only factors that significantly influenced Germany’s position in the world after the Second World War. As stated above, the territories with natural resources and a developed industry were under foreign control. On top of that the allies completely disarmed Germany. For the FRG this meant the abolishment of all munition factories and a severe restriction on civilian 5 industries which had a military potential. In practice this meant all civilian industries. In the DDR, the industry was massively dismantled, even fiercer than in the Western part. To make up for the expenses of war, the USSR shipped many factories to the USSR, leaving the economy of the DDR in an even worse position (Bessel, 2009). This historical sketch of a devastated and utterly divided country is the frame in which Germany’s process of reconciliation with it’s past had to take place. As mentioned, in the years after the war the atrocities and cruelties that had taken place under the Nazi-regime became more and more visible. It would not be easy for Germany to overcome what had happened in their country, but, as will become clear later on, Germany did manage to become one of the key components of a united Europe today. 1.2 Development of identity: Guilt Tracking the development of identity in such a divided country is not easy. Most scholars investigating Germany’s reconciliation focus on the Western part of Germany, only to include the Eastern part after the unification in 1990 (Hein, 2010). It is most intriguing to see how differently both countries tried to cope with the past. For the Western part, the process is often summarized into one word; guilt. In East-Germany the process is clearly linked with a rigid process of denazification. The picture of Willy Brandt at the beginning of this part illustrates the identity of guilt perfectly. Brandt was chancellor of West-Germany when he kneeled towards the victims of the Warsaw ghetto uprising in 1970. When an interviewer asked about his motives, this was his response: "Under the weight of recent history, I did what people do when words fail them. In this way I commemorated millions of murdered people" (Willy-brandt.org). His gesture empowered the treaty which West-Germany signed in which Germany accepted the new borders of Poland (Hein, 2010). In this paragraph it will first be described what guilt meant for WestGermany and secondly what it meant for the development of identity in the DDR. After the surrender of Nazi Germany in 1945 Germany had to redefine its national identity without neglecting its past in order to become a well-respected and trusted country again and to become a part of the global league of democratic nations (Nugent, 2010). This process of incorporating or coming to terms with the past is also known as the Vergangheitsbewältigung. 6 Some historians have interpreted this process as mastering the past. Once the past is mastered, there is a clear end in sight and once this goal is reached, Germany can again be a 'normal' country. This concept of normal country will also be discussed with Japan in the second part of this paper. In the 21st century, it has become hard to argue against the idea that Germany, the greatest economy in Europe, is not a normal country. Nonetheless, there seems not to be an end yet in the process of reconciliation and after the reunification of 1990 there even seemed to be a renewed urgency to deal with the national socialist past (Nugent, 2010). Germany did not willingly embarked on reckoning with the National Socialist past immediately after the War. The occupying forces jump started this process by making local populations visit the former concentration camps and later of course with the impactful Nuremberg Tribunals. The popular reaction was one of disbelief, horror and resentment (Nugent, 2010). In the 1960s, the sentiments of the Germans with regards to the wartime past seemed to be focused on moral reconstitution. The new generation demanded answers from their elders. This family discourse led to an emerging culture of memory in the 1980’s (Nugent, 2010). Besides these private memories there was a political movement of collective memory, materialized into monuments and museums. Of course there are many aspects of this memorization which were not material but were still of great importance. About this, Hein (2010) states the following: Some of Germany’s contributions that have been highly regarded abroad include its frank apologies for its war guilt to Poland, France and other European nations; the legal prosecution of former war criminals (ie Auschwitz trial); the compensation for former slave laborers; the voting of a no time limit statute for prosecuting NS crimes; a national civil memorial for all the victims of war; the legal prosecution of those who deny the Holocaust; the thorough documentation and public exhibition of war crimes committed by German soldiers; educational reconciliation cross border exchange activities and so forth (p.147). This summary lists many influential moments in Germany’s process of becoming a normal state. By no means it does justice to these events by only mentioning them, like the Warschauer Kniefall by Willy Brandt, there is much more to be told. However the focus of this paper is to 7 investigate how these events influenced Germany’s identity of guilt and therefore we will not go in further on these events. The identity of guilt is something that is not be underestimated. It influenced West-Germany, and the reunificated Germany, in all possible ways. In the Eastern part of Germany the process of reckoning with the past took a different form, which was highly influenced by the communist regime. The most important aspect of this process was the denazification of Germany. In East-Germany this cannot be separated from the communist ideals. The former large landowners, often militaristic Nazi’s with a Prussian background, were arrested and their possessions were redistributed among farmers. Furthermore, most industries were dismantled and shipped to the USSR, which the latter classified as being 'war reparations'. The strong dominance of Prussian symbols and buildings were perceived by the Soviets as a representation of national socialist, nazi, history and therefore the link between the German identity and Prussia was demolished. To replace the old national identity, a new (communist) identity emerged, forced unto the Germans by means of education and, as stated before, denazification. This denazification entailed a demonization of West-Germany as the prolongation of the national socialist movement in a new state. The ‘new’ identity in EastGermany was not so much influenced by a sense of guilt but rather by a sense of demonizing the Nazi regime, and especially their violence against the communists (Nugent, 2010). After the reunification of Germany in 1990, the two identities had to merge into a new national identity. The process of reconciliation once again become an important topic and for Germany it was clear that Germany was not yet a ‘normal nation’. This is why, seventy years after the Second World War, it might still be too early to say that ‘the last day of the war’ has come (Nugent, 2010). The impact the War has had on the German identity is, at least, still very much apparent. 1.3 Regional context The importance of the regional context has been shortly addressed in the first part of this chapter, but here it will be discussed in more detail as it is actually one of the most important subjects in analyzing German reconciliation. As stated, West-Germany was occupied by Western forces after 1945. Consequently this meant that during the Cold War West-Germany belonged to the 8 ‘Western’ part of the world. This manifested itself in financial aid from the United States and in cooperation with other countries in Western Europe. In 1952 the European Coal and Steel Community was formed between Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Italy, France and West-Germany. The community was installed to promote cooperation and prevent a new war between Germany and France, starting with the key-components needed for warfare and later on growing into a common European market in 1993. Interestingly West-Germany was not excluded from this European cooperation. On the contrary: it was intendedly included from the beginning. For West-Germany this ultimately led to steady economic growth and paved the way to become the biggest economy in Europe (IMF, 2014). The regional cooperation had some other side-effects of which the most important here is that it accelerated the process of reconciliation. When this Community was created, coal and steel were key-components in the economy. Consequently, creating a united market meant a high level of interdependency between the six core-states in the Community. France and West-Germany were dependent on each other which made the political pressure for an official apology for former war-crimes higher. The willingness, whether or not pressured by the US, to include West-Germany in political and economic cooperation in Europe can be seen as one of the most important factors in the German reconciliation process (Conrad, 2003). In the Eastern part of Germany the story is somewhat different. As stated before, it was occupied by the Soviet forces and therefore became a part of the communist bloc during the Cold War. Although East-Germany was communist, it wasn’t incorporated in the USSR. In October 1949, the USSR withdrew its headquarters from Berlin and surrendered its installed government to the new German state. As mentioned in the last paragraph, under the communist regime there was a fierce process of denazification, focusing on the Nazi’s violence towards communists. The communist identity was pushed unto the inhabitants of the DDR, destroying the former relation between Germany and Prussia. Numerous Prussian symbols were torn down such as the Junker manor and the Berliner Stadtschloss. The new identity founded itself on the progressive history of Germany, in the light of Communism, such as the German Peasants’ war which was seen as a class struggle during Prussia’s industrialization (Bessel, 2003). The emphasis on the identity of guilt was not that strong in the DDR due to their communist identity. It was not the holocaust that was remembered, it was the violence against the Communists. After the reunification in 9 1990 Germany had to merge both ‘identities’ which resulted in an emphasis on the holocaust, expressed by symbols such as the Memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe (Stern & Maier, 1989). 10 2. Japan Image: The Red Bench, Onomichi, Japan, 2005 (Wim Wenders) 2.1 Post-Second Worl war situation Wim Wenders, a German film director, photographer and writer and the Australian writer and philosopher Mary Zournazi, recently published a book called Inventing Peace; a dialogue on perception. In this book, the writers reflect upon the ways in which we, humans, perceive war, injustice, violence and, most importantly, peace. Wenders took the picture above in Onomichi Japan in 2013. 11 In the 1980s Wenders began a long-running photographic project, Pictures from the Surface of the Earth, for which he travelled around the globe, capturing images in countries such as Australia, Cuba, Israel, Japan, and the United States, characterized by quiet, desolate landscapes and scenes. What we can see on the picture above is an unoccupied bench, which overlooks an enormous battleship. Behind the two is just a metallic railing. Onomichi is a small city located in the prefecture Hiroshima, a city famous for the the fact that is was as good as destroyed completely by an atomic bomb dropped by the US in August 1945, close to the end of the War. The picture, in our opinion, very well portrays the identity of Japan after the Second World War. On the one hand we can see a peaceful, quiet image of an empty bench. On the other hand, we can see an enormous battleship that can only serve military purposes. Peace on the one side of the railing, war on the other. As will become clear in this part of the paper, this picture portrays Japan's ambiguous relationship with military developments. Before we go into further detail concerning the Japanese identity, a small outline of the coming chapters will be given. In previous chapter the wartime legacy of Germany has been discussed as well as the extent to which Germany has reconciled with the past. As for Germany, first the main events that have occurred in the Japan in the period after the Second World War will be examined, as a sort of introduction to the topic. Secondly, the development of the Japanese identity in the post War period will be discussed. Then thirdly, and finally, the effects the development of this specific identity has had on the place of Japan in its region will be examined. Let us now start with a small recap of Japan’s involvement in the Second World War. When thinking about Japan’s involvement in the Second World War, what generally comes to mind is the Japanese attacking the Americans in Pearl Harbor and the US counterattacking by dropping two atomic bombs on the country, one in Nagasaki and one in Hiroshima. For many Westerners, this is all that is known about Japan’s involvement in the War. What is often failed to be realized is that the people of countries located in the South-East Asian region have witnessed equal horrors and atrocities as those that have been committed by the Germans in Europe. Therefore, a very brief account of what happened before, during and after the War will be discussed below. 12 As opposed to most other Asian countries, amongst which India and great parts of China, Japan was never under imperial rule by the West. On the contrary, inspired by the Western imperialists, Japan developed itself to becoming an imperialist itself. This started already at the end of the 19th century, when Japan invaded the island of Formosa, now known as Taiwan (Dower, 1999). This can be seen as the start of Japan’s ‘holy war’, as Japan's imperial conquest is often called. This name refers to the dominant Shinto religion of Japan at the time, in which the Japanese king was seen as sacred and divine, and the Japanese people as superior and destined to rule over the other peoples (Skya, 2009). In this respect, the Japanese military conquest is somewhat similar to the German, as they were both largely based on ideology. The similarities between the two countries will be further examined in the discussion. In 1910, Japan annexed Korea and continued expanding, which eventually led to the country occupying large parts of Asia, including a significant deal of China. Retrospectively, it could be said that Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 was its biggest mistake, as this event provoked the US to heavily counterattack Japan, most significantly in Hiroshima and Nagasaki of course, with the use of two atomic bombs in August 1945 (Wohlstetter, 1962; Poolos, 2008). One month after the nuclear attacks had occurred, Japan surrendered to the US. After this, the US took control of the country to prevent further transgressions (Allinson, 2004). Pressured by the US, Japan renounced all rights to go to war. Under the Yoshida doctrine, implemented by former Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, Japan’s identity changed significantly. Following this doctrine, Japan completely relied on the US for providing safety in the region, while Japan itself could focus completely on economic recovery. Which it did, as by the time that solely thirty years had gone by, Japan had transformed itself to an ‘economic giant and a political or military pygmy’ (Yahuda, 2013). Japan became the world’s second largest economy in the 1968 and only recently lost its place to China, to become the third largest economy (the Guardian, 2010). Despite the country's own swift recovery, the devastating impact Japan’s imperial conquest had on the East-Asian region would be long-felt. As J.W. Dower describes (1999): “From the rape of Nanjing in the opening month of the war against China to the rape of Manila in the final stages of the Pacific War, the emperor’s soldiers and sailors left a trail of unspeakable cruelty and rapacity.” With ‘rape of Nanking’ and ‘rape of Manila’, Dower refers to two of the most well 13 known war crimes Japan has committed during the war, in which both mass murder as well as mass rape were committed. As we will see, Japan has not yet reconciled with its regional neighbors, and thus its past, with regards to the atrocities committed. 2.2. Development of Identity: Shame Ever since the end of the Second World War, Japan has made strong efforts to change its image from a hostile to peace-loving nation. Pressured by the United States, Japan has even laid down the renunciation of war in its Constitution. This can be found in Article 9 of the Constitution of 1947, which says: Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized (1947). Under the Yoshida doctrine, the importance of the renunciation of war was very much appreciated by the Japanese people. Here, the sentiment of shame played a key role with respect to the atrocities committed in the War. By focusing on economic developing and staying out of military and political matters as much as possible, Japan wanted to show the world its peaceful intentions were sincere. Simultaneously, the Japanese have tried to push the wartime atrocities to the side and move on without proper reconciliation. This attitude has not changed yet: even last year several Japanese broadcast officials publicly denied the war crimes Japan has committed, announcing that the US made them up (Spitzer, 2014). Furthermore, it is often argued that Japanese schoolchildren are never taught about the atrocities committed, as these events have been omitted the history books (Oi, 2013). According to Oi (2013), this is also the reason that “Japanese people often fail to understand why neighboring countries harbor a grudge over events that happened in the 1930s and 40s.” The issue of Korean ‘comfort women’ is another reason for grudge, as Japan believes those women have worked as paid prostitutes whilst Korea says they were used as sex slaves instead. This denial can largely be attributed to the prevailing culture of shame in Japan, in which the Japanese cover up their history like Adam and Eve used leaves to 14 cover up themselves once they first experienced shame for their nakedness (Lee, 2013). R. Benedict, who studied shame culture in Japan for several years, said that “Shame cultures do not provide for confessions, even to the Gods. They have ceremonies for good luck rather than for expiation” (1978). As we will see in the next chapter, this shame culture significantly burdens Japan’s regional relations. Interestingly, over the years Japan’s shame with regards to the atrocities it has committed somewhat seems to have developed into shame with respect to the military constraints it had committed itself to. This has everything to do with the ambiguity between on the one hand having great economic power and having so little military and political power on the other hand. Former Japanese politician, Ichiro Ozawa first introduced the concept of Japan needing to become ‘normal country’ in his book Blueprint for a New Japan, which he published in the early nineties (Ozawa, Rubinfien & Gower, 1994). Ozawa wrote his book after the Gulf War in which Japan was, because of its constitutional constraints, only able to contribute to the UN’s peacekeeping operations in the form of financial aid. For Ozawa, a normal Japan meant a nation that could physically participate in these international peacekeeping activities, not only by means of ‘checkbook diplomacy’ (Funabashi, 1991). One year after the Gulf war, in 1992, Japan enacted the International Peace Cooperation Law to become able to send troops to peacekeeping missions. As a result, Japan became able to get involved in UN missions with other means than solely money. This law did create friction with the constitutional restraints of the country, as here the right to go to war was renounced entirely, no matter the situation. In the post-Cold war era, we can increasingly see a Japan that is more and more becoming a strong military power, not dependent on the US security troops. The Japanese government has recently declared that it is vital for Japan to cope with a tough security environment, including the rise of an “increasingly assertive China and an unpredictable North Korea” (Takenaka, 2013). Understandable to a certain extent but every military development still has to be accounted for with regards to Article 9 of the Constitution, which ‘forces’ the government to find ways to act around this constitutional requirement, as well as to its regional neighbors who are closely watching Japan’s military expansions (Kelly, 2014). Concluding from the matters discussed above, it can be said that whereas Japan's identity is still largely based on shame and 15 hiding away the wartime history, the country is increasingly moving away from the military constraints that have been codified in its Constitution. This is the ambiguity that could be perceived in the Red Bench picture: peace on the one side; military expansion on the other. 2.3. Regional context With respect to its strongly developed economy, mainly dedicated to high-end technology, Japan soon took up the role as ‘leading goose’ in the region (Lam, 2006). Following this paradigm, Japan took on the task to lead neighboring countries such as South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore to greater economic development. Despite its economic strength, something significant stood in the way that withheld the countries from becoming close partners namely reconciliation with the past. Many atrocities committed have not been fully apologized for or, worse, have even been completely denied by Japan. As Lind (2008) mentions: “Japan’s attempt to come to terms with the past is has been fraught, polarizing, and diplomatically counterproductive”. Nonetheless, especially in the last few decades, Japan has increasingly tried to increase regional cooperation. Important examples of this are Japan’s strong involvement Asian Political Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the Asean Regional Forum (ARF) (De Brouwer & Wang, 2004) Yet, Japan’s post World War attitude in the region has been pragmatic and solely based on economic welfare. Japan will now have to convince its neighbors that it is willing to cooperate not only for its own economic gain, but also for broader regional economic development. Furthermore, in many ways, Japan has yet to formally apologize to its neighboring countries for the war crimes it has committed before and during the Second World War. The fact that the War is still a very sensitive topic in the region can, amongst others, be derived from the event described below. In December 2013, Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo visited the Yasukuni shrine, a Second World War memorial. By doing so, he infuriated both China and South Korea. This shrine is used to honor Japan’s fallen soldiers, including many convicted war criminals. Even though Abe called his visit an anti-war gesture, China responded by calling the visit "absolutely unacceptable to the Chinese people", and South Korea expressed "regret and anger" (Wingfield, 2013). The protests that followed in China and South Korea when Shinzo Abe visited or even paid attention to the Yasukuni shrine over the last few years are expressive. It shows that Japan has not yet 16 been forgiven and that the past has not been reconciled with, which, combined with recent military expansions by Japan and other neighbors, strongly increases tensions in the region. 3. Analysis In the analysis we will highlight some similarities and differences in the way Germany and Japan have reconciled with their past. We will first describe the military ‘expansion’ of both countries after the Second World War. Consequently we will look at the term ‘Entangled memories’ to illustrate the importance of the national paradigm in studying history concluding with a critical note concerning the judgment of both processes of reconciliation. 3.1 Military expansion Comparing the two countries, it appears that post-War Germany has been able to reestablish itself as a strong military power long before Japan has. In the aftermath of the War, Germany was one of the six European countries that got together to form the European Coal and Steel Community. By the creation of this institution in 1951, a common market was created that served to preserve peace by promoting trade and interdependence (EU matters, 2014). At the same time, these countries established the European Defense Community in order to unite their armies. An integrated European army has, to this day, not made reality. This does not change the fact that the situations in Germany and Japan are completely different: whereas Japan’s neighbors are still very anxious about any possible military expansions by Japan, this is not the case at all for Germany. This could be, as Prof. C. Schetter argues: Because Berlin is always careful to stay closely in sync with its allies. Germany’s security priorities are strictly in line with those of Europe and the US. It is quite unthinkable that Germany would embark on a military mission of its own (Ford, 2014). Under Shinzo Abe’s rule, Japan has moved further and further away from the pacifism and passivism it carried out under the Yoshida doctrine. As mentioned before, this continuously leads to strong reactions by its neighbors. Last year, South Korea's foreign ministry expressed the following: 17 As a pacifist nation, Japan is expected to adhere to basic principles and implement them to a direction of contributing peace and stability. The principles should be carried out with the maximum level of transparency in consideration of concerns held by neighboring countries (Ford, 2014). The reason for the dissimilarity between the ways in which the two countries’ military expansions are perceived in their respective regions seems to be based largely on the (lack of) reconciliation with the past. The difference in the degree of reconciliation, then, might be due to the different paths the two countries have taken after the War. Whereas Germany, as mentioned, has focused on repairing the relations in the region from the start, Japan has focused on repairing its relation with the US. Japan has neglected the atrocities it has committed in its own region and as a result one could say that in a military perspective Germany became a ‘normal’ country again, long before Japan would be allowed to have it’s own military. Besides the military aspect in both countries there are a lot more similarities and differences which could be highlighted, especially regarding todays the political position of both countries in their specific regions. However we will argue that the national paradigm alone might not be enough to compare both countries. The importance of both the region and the way history is remembered must be taken into account as well. 3.2. Entangled memories While studying the history of Japan and Germany the national paradigm is dominantly present. The past is often interpreted as a matter of national culture. Japan’s incapability to deal critically with its past is explained as a product of their national identity built around the concept of shame. In Germany, the Vergangenheitsbewältigung is often seen as a process of collective learning, neglecting the fact that Germany has not been the same territorial and cultural entity in the decades after the war (Conrad, 2003). Therefor the national perspective on the process of reconciliation cannot be the only perspective, it is always linked to the transnational context, which Conrad calls ‘Entangled memories’. Japan’s incapability to deal critically with its past is linked with the American dominance in Japan after the Second World War. An example of this American dominance is the naming of the war. The Second World War was called ‘The greater East Asian war’ until 1945, than the ‘Pacific War’ became the official name for the war in Japan. 18 For the Japanese historians the US had a privileged position which led to the marginalization of the Japanese involvement in the war on the Asian mainland and islands, a process Karatani Kôjin has called the ‘De-Asianization’ of the postwar discourse (Kôjin, 1993). The way Japan perceived itself changed over time, the national identity became more and more influenced by America, Conrad (2003) says the following: ‘America’s Japan became Japan’s Japan’ (p.93). In East-Germany the same can be said about the Soviet dominance on the process of forming a new identity, based on the communist principles. The importance of these entangled memories is in the fact that the process of reconciliation is not merely a national affair. The way how history is remembered and portrayed in Japan and Germany is clearly influenced by the dominant forces at work in both countries. Therefore it is interesting to complement the dichotomy of the ‘culture of guilt’ and the ‘culture of shame’ with an ‘Entangled version’ of history. Keeping that in mind, it becomes even more difficult to compare the process of reconciliation in both countries. It is not as black and white as the labels guilt and shame make it seem. Jennifer Lind (2008) once more emphasizes this in an article titled: What Japan Shouldn’t learn from Germany. Although this title might suggest that Lind here explains what Germany has not done better than Japan (with regards to the post-War reconciliation), this is really not the case. What can be concluded from her text is that the two situations are, in fact, so different that Germany cannot not one on one be used as an example for Japan. Of course, there are things that Japan should have done differently in order to restore the relations with its neighbors. Above, the examples of comfort women, the history books and the Yasukuni Shrine have been named. Those are extremely sensitive topics in the Asian region still today and if Japan wants to come to proper terms with its past, it will have to change its attitude here. On the other hand, it must be said that to restore a relationship, both parties must be willing to do so. Japan's former apologies have been perceived by its neighbors to be contradictory as well as either too late or insufficient (or both). This perceivance seems to be somewhat preconceived and, combined with the shame culture of Japan that makes apologizing extremely difficult, the road to reconciliation in the East Asian region is still very long. How history is remembered and the effects on the national identity make it difficult to judge both countries, or even to compare them. 19 Conclusion In this paper, an answer has been sought to the question To what extent have Germany and Japan reconciled with their wartime histories, and how has this influenced their role in the region, respectively Central Europe and East Asia. In certain respects we have seen that Germany can serve as an example for Japan. For instance with respect to the visits the Japanese Prime Minister has paid to the Yasukuni Shrine, in which convicted wartime criminals are honored. Nonetheless, it should be understood that, as Lind (2008) mentions, the two situations are different to such a great extent that it would be one-sided to say that Germany is good and Japan is bad in terms of reconciliation. In the case of Germany, we have seen that its neighbors were very much dependent on close corporation for economic development but also for providing a strong unity opposing the East European communist the bloc. Japan, on the other hand, focused more on maintaining a strong relationship with the US and hereby lacked the direct urgency to reconcile with the region that Germany did have. An inclusive answer to the question above has, unfortunately, not been found to the question above. This because the topic is too extensive and complicated to cover in solely one paper. The topic needs, and in our opinion, deserves further examination. Realizing that this year celebrates the seventieth anniversary of the end of the War, this was our attempt to contribute to a closer understanding of the impact the Second World War has had on today's day and age. 20 References Allinson, Gary D. Japan's Postwar History. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2004. Print. Benedict, Ruth. The Chrysanthemum And The Sword. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1978. Print. Bessel, Richard. Germany 1945. New York: HarperCollins, 2009. Print. Bessel, Richard. 'Policing In East Germany In The Wake Of The Second World War'. chs 7.2 (2003): 5-21. Web. Connors, Michael Kelly, Davison, and Dosch. The New Global Politics Of The Asia-Pacific. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004. Print. Conrad, S. 'Entangled Memories: Versions Of The Past In Germany And Japan, 1945--2001'. Journal of Contemporary History 38.1 (2003): 85-99. Web. De Brouwer, Gordon, and Yun-jong Wang. Financial Governance In East Asia. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004. Print. Dower, John W. Embracing Defeat. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1999. Print. Eumatters.ie,. 'Why Was The EU Founded?'. N.p., 2011. Web. 17 Mar. 2015. Ford, Peter. 'Japan, Germany Shake Off WWII Arms Constraints. A Cause For Concern?'. The Christian Science Monitor. N.p., 2014. Web. 22 Apr. 2015. Funabashi, Yoichi. 'Japan And The New World Order'. Foreign Affairs 70.5 (1991): 61. Web. Harris, Peter. 'Why Japan Will Never Be A Permanent Member Of The UN Security Council'. The National Interest. N.p., 2014. Web. 17 Mar. 2015. Hein, Patrick. 'Patterns Of War Reconciliation In Japan And Germany. A Comparison'. East Asia 27.2 (2010): 145-164. Web. Imf.org,. 'Report For Selected Countries And Subjects'. N.p., 2014. Web. 29 Apr. 2015. Inoguchi, Takashi, and G. John Ikenberry. The Troubled Triangle. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. Print. 21 Katsumata, Hiro, and Mingjiang Li. 'Asia Times Online :: Japan News And Japanese Business And Economy'. Atimes.com. N.p., 2008. Web. 19 Mar. 2015. Katsuno, Masatsune. Japan’s Quest For A Permanent Seat On The United Nations Security Council. 1st ed. Tokyo: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2012. Web. 17 Mar. 2015. Kelly, Tim. 'Japan Begins First Military Expansion In More Than 40 Years'. Business Insider. N.p., 2014. Web. 13 Apr. 2015. Lam, Peng Er. Japan's Relations With China. London: Routledge, 2006. Print. Lee, Kalliope. 'The Desperate Cover-Up Of A Shame Culture: The Provenance Of Mayor Hashimoto's Incendiary Comments About The Necessity Of Comfort Women'. The Huffington Post. N.p., 2013. Web. 13 Apr. 2015. Lind, Jennifer M. Sorry States. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008. Print. McGrew, Anthony G, and Chris Brook. Asia-Pacific In The New World Order. London: Routledge, 1998. Print. Mofa.go.jp,. 'MOFA: An Argument For Japan's Becoming Permanent Member'. N.p., 2014. Web. 19 Mar. 2015. Nichibenren.or.jp, 日本弁護士連合会‚Japan Federation Of Bar Associations: 64Th JFBA General Meeting - Resolution Opposing The Approval Of Exercising The Right To Collective Self-Defense'. N.p., 2013. Web. 19 Mar. 2015. Nugent, Christine Richert. German Vergangenheitsbewältigung, 1961 - 1999. 2010. Print. Oi, Mariko. 'What Japanese History Lessons Leave Out'. BBC News. N.p., 2013. Web. 13 Apr. 2015. Orzoff, Andrea. 'Orderly And Humane: The Expulsion Of The Germans After The Second World War'. The Journal of Modern History 86.3 (2014): 657-659. Web. Overy, R. J., and Ian D. Turner. 'Reconstruction In Post-War Germany: British Occupation Policy And The Western Zones, 1945-1955.'. The Economic History Review 44.1 (1991): 22 192. Web. Ozawa, Ichiro, Louisa Rubinfien, and Eric Gower. Blueprint For A New Japan. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1994. Print. Pierre Fatton, Lionel. 'Is Japan Now Finally A Normal Country?'. The Diplomat. N.p., 2013. Web. 19 Mar. 2015. Poolos, Jamie. The Atomic Bombings Of Hiroshima And Nagasaki. New York: Chelsea House, 2008. Print. Seig, Linda. 'Veteran Politician Ozawa: Japan PM's Policy Shift Risks Dangerous Path'. Uk.reuters.com. N.p., 2014. Web. 19 Mar. 2015. Skya, Walter. Japan's Holy War. Durham: Duke University Press, 2009. Print. Spitzer, Kirk. 'Japanese Broadcast Official: We Didn't Commit War Crimes, The U.S. Just Made That Up'. TIME.com. N.p., 2014. Web. 13 Apr. 2015. Stern, Fritz, and Charles S. Maier. 'The Unmasterable Past: History, Holocaust, And German National Identity'. Foreign Affairs 68.4 (1989): 209. Web. Takenaka, Kiyoshi. 'Japan Says Faces Increasing Threats From China, North Korea'. Reuters. N.p., 2013. Web. 13 Apr. 2015. the Guardian,. 'China Overtakes Japan As World's Second-Largest Economy'. N.p., 2010. Web. 8 Apr. 2015. Willy-brandt.org,. 'Bundeskanzler Willy Brandt Stiftung: Zitate Von Willy Brandt'. N.p., 2015. Web. 25 Apr. 2015. Wingfield, Rupert. 'Japan PM Shinzo Abe Visits Yasukuni WW2 Shrine'. BBC News. N.p., 2013. Web. 27 Mar. 2015. Wohlstetter, Roberta. Pearl Harbor; Warning And Decision. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1962. Print. Yahuda, Michael B. Sino-Japanese Relations After The Cold War. London: Routledge, 2013. 23 Print. Yahuda, Michael. The International Politics Of The Asia Pacific. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis, 2011. Print. 24