Document 10744574

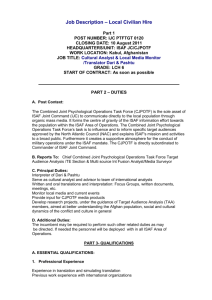

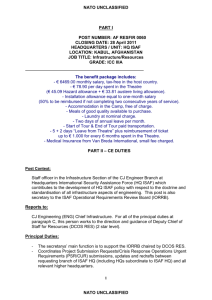

advertisement