FINANCIAL ADAPTATION THROUGH PARAMETRIC INSURANCE PRODUCTS:

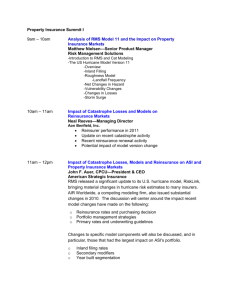

advertisement