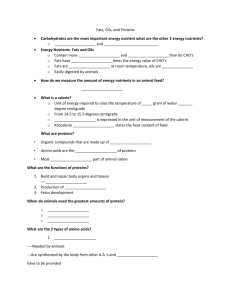

IT [NATIONAL NUTRITION PLANNING

advertisement