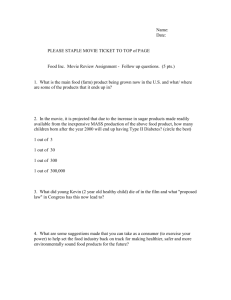

inf orms

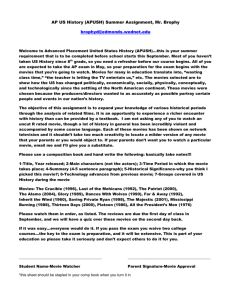

advertisement