Running head: ORANIZATIONAL CULTURAL COMPETENCE AND OUTREACH i

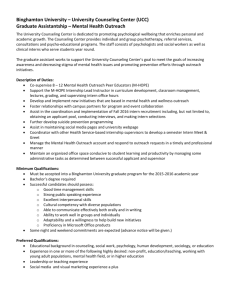

advertisement