PANAMA

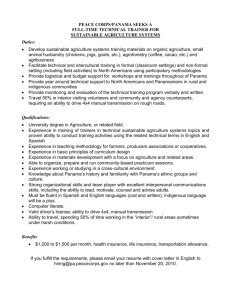

advertisement

PANAMA TRADE SUMMARY In 2000, the U.S. trade surplus with Panama was $1.3 billion, a decrease of $75 million from the U.S. trade surplus of $1.4 billion in 1999. U.S. merchandise exports to Panama were $1.6 billion, a decrease of $133 million (7.6 percent) from the level of U.S. exports to Panama in 1999. Panama was the United States’ 45th largest export market in 2000. U.S. imports from Panama were $307 million in 2000, a decrease of $58 million (15.9 percent) from the level of imports in 1999. The stock of U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) in Panama in 1999 amounted to $33.4 billion, an increase of 28.7 percent from the level of U.S. FDI in 1998. U.S. FDI in Panama is concentrated largely in the finance, petroleum and wholesale sectors. IMPORT POLICIES Panama joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in October 1997. WTO accession and implementation laws passed under the previous Panamanian administration liberalized the country's trading regime by reducing the average tariff level to one of the lowest of any Latin American state, averaging 15% for agricultural goods and 8.25% overall. The current Moscoso Administration, which entered office in September 1999, raised some agriculture and food tariffs substantially. In October 1999, the Government of Panama raised tariffs on an assortment of 44 farm products to the highest rates possible under Panama's WTO commitments. Tariff rates for these products now average over 56 percent. Examples include poultry at 293 percent, rice at 123 percent, evaporated milk at 165 percent, and sugar at 152 percent. U.S. exports to Panama most affected by the hikes are pork (81%) and potatoes (86%). Panama's WTO schedules provide for high duties throughout much of their 5-year phase-out period. Nevertheless, current Panamanian tariffs overall remain relatively low. Of greater concern has been the new government's use of sanitary/phytosanitary (SPS) permits as an arbitrary import licensing system, in apparent contradiction of Panama’s WTO commitments. The situation improved somewhat in late 2000 under the direction of a new Agriculture Minister. However, SPS procedures are still subject to arbitrary application. Panama is not a member of the Central American Common Market or any other subregional economic group. It currently has limited bilateral agreements with Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. It continues trade negotiations with Chile, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and several Central American countries individually, as well with the Central American Common Market. STANDARDS, TESTING, LABELING, AND CERTIFICATION Panama's standards and certification regime generally conforms to WTO standards. However, restrictions have been applied from time to time in response to sectoral unease with Panama's trade liberalization. One area of special concern for U.S. exporters has been the long waiting period for sanitary and phytosanitary import permits. Throughout the first year of the Moscoso administration, the Ministry of Agriculture (MIDA) often took 30 days or more to issue the permits. Products hit especially hard by this practice have been beef, pork, and potatoes. The Government of Panama's practice of arbitrarily delaying the issuance of SPS permits, or simply not responding to requests, appears to be at odds with WTO commitments. There has been some positive movement with the appointment of a new minister of agriculture in September 2000, but some arbitrariness remains in the system. Panama requires that Panamanian health and agriculture officials certify U.S. processing plants as a condition for the import of poultry, pork, and beef products. U.S. exporters have assisted Panamanian officials in making inspection visits to U.S. plants. There have been no instances of a FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS 341 PANAMA U.S. plant failing to be certified, but inspections have been delayed many times for various reasons, including lack of personnel and budgetary constraints in the responsible Panamanian ministries. Discussions to address this matter continue. The U.S. considers it a high priority to obtain Panama's recognition of U.S. government certification of packing plants, in order to eliminate the current plant-by-plant approach. While importers of non-agricultural products must register them with the Ministry of Commerce and Industry before distribution or sale in Panama, procedures for registration are straightforward and evenly applied. There are no comprehensive labeling or testing requirements for imports. GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT Panama's government procurement regime is governed by Law 56 and managed by the Ministry of Economy and Finance. The law provides for a transparent bidding process for government contracts, but allows for exceptions, such as procurements for national defense. One such exception was invoked by the Government of Panama in the privatization of the Port of Balboa in 1998 to Hutchinson-Whampoa, a Hong Kongbased company. Some American firms thought the bidding process that preceded this decision was unorthodox and mishandled. In contrast, bids for the state telecommunications company and the power generation and distribution facilities were generally considered to have been well-organized and transparent. As part of its accession to the WTO, Panama agreed to pursue accession to the plurilateral Government Procurement Agreement. Progress towards accession has slowed considerably in the past year, and the current government’s intentions are uncertain. One particular concern remains the Panama Canal Authority (PCA), which the Government of Panama has thus far resisted including in its accession offer. The U.S. has raised concerns regarding Panama’s stance in the GPA accession negotiations, as well as lack of 342 cooperation in the WTO Working Party on Transparency in Government Procurement. As a result of these concerns, the U.S. in December 2000 suspended a waiver of “Buy America Act” provisions which had previously been applied to Panama. EXPORT SUBSIDIES Panamanian law allows any company to import raw materials or semi-processed goods at a duty of three percent for the processing and sale in the domestic market, or duty free for export production. The Government of Panama has been considering eliminating these provisions, under strong pressure from domestic agriculture producers alleging abuse by importers. Companies not already receiving benefits under the Special Incentives Law of 1986 are allowed a tax deduction of up to 10 percent of their profits from export operations through 2002. Because of its WTO obligations, Panama has revised its export subsidy policies. The Tax Credit Certificate (CAT), given to firms producing non-traditional exports when the exports' national content and value added meet minimum established levels, will be gradually phased out. The policy has allowed exporters to receive CATs equal to 15 percent of the export’s national value added until after the year 2002, down from 20 percent prior to 1998. After 2002, the program will be eliminated. The certificates are transferable and may be used to pay tax obligations to the government, or they can be sold in secondary markets at a discount. The government has become stricter in defining national value added, attempting to reduce the amount claimed by exporters. A number of industries that produce exclusively for export, such as shrimp farming and tourism, are exempted from paying certain types of taxes and import duties. The Government of Panama uses this policy to attract foreign investment, especially in economically depressed regions, such as the city of Colon. Companies that profit FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS PANAMA from these exemptions are not eligible to receive CATs for their exports. Law 25 of 1996 provides for the development of "export processing zones" (EPZ's) as part of an effort to broaden the Panamanian manufacturing sector while promoting investment in former U.S. military bases transferred to Panama. Companies operating in these zones may import inputs dutyfree if products assembled in the zones are to be exported. The government also provides other tax incentives to EPZ companies. INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS PROTECTION Protection of intellectual property rights (IPR) in Panama has improved significantly over the past several years. However, some international businesses and U.S. government officials remain concerned about inadequate border measures to combat transshipment of counterfeited goods through Panama and about enforcement deficiencies in the Colon Free Zone (CFZ). Panama is a member of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the Geneva Phonograms Convention, the Brussels Satellite Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, and the International Convention for the Protection of Plant Varieties. In addition, Panama was one of the first countries to ratify the WIPO Copyright Treaty and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty. Intellectual property policy and practice in Panama is the responsibility of an Interinstitutional Committee. This committee consists of representatives of six government agencies and operates under the leadership of the Vice Minister of Foreign Trade. It coordinates enforcement actions and develops strategies to improve compliance with the law. Over the past several years, Panamanian authorities have conducted numerous raids against large video piracy operations, and several cases are pending in the courts. The operating permits of some CFZ companies have been suspended as a result, but transshipment of pirated goods remains a serious problem. The Anti-Monopoly Law (1996) provides for the establishment of special courts to deal with commercial cases, including those involving intellectual property infringement. Two district courts and one superior tribunal began to operate in June 1997 and have been adjudicating patent and trademark disputes. The Panamanian Government, the U.S. Government and private interests have sponsored numerous seminars in 1999 and 2000 to train prosecutors, judges, and other officials in intellectual property laws and procedures. Some U.S. intellectual property owners have experienced significant delays when they have sought infringement remedies in the Panamanian judicial system. Panama is in the process of modernizing its copyright registration and patent and trademark registration capabilities. The Government is also drafting amendments to its copyright law that would fully implement the new WIPO treaties. An initiative which would consolidate copyright, patent, and trademark functions into a single autonomous entity and another initiative to create a specialized Prosecutor's Office for IPR have been delayed due to resource constraints and government transition. Copyrights Panama’s copyright legislation dates from 1994, and is based on a World Intellectual Property Organization model. The law modernizes copyright protection in Panama, provides for payment of royalties, facilitates the prosecution of copyright violators, protects computer software, and makes copyright infringement a felony. Although the lead prosecutor for intellectual property cases in the Attorney General's Office has taken a vigorous enforcement stance, the FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS 343 PANAMA Copyright Office remains small and ineffective, and Panama's judicial system has not provided speedy and effective remedies for private civil litigants under the law. The Copyright Office is in the final steps of drafting further improvements to the Copyright Law to implement the new WIPO treaties (the WIPO Copyright Treaty and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty) and also to establish new offenses, such as for internet-based copyright violations, to raise the penalties for infractions, and to enhance border measures. This proposed draft legislation is moving forward with technical assistance from SIECA (the Central American Economic Integration System). In December 2000, President Moscoso signed an executive decree ordering the legitimization of current software inventories and all future use in government offices, including autonomous agencies. The decree took effect January 1, 2001, and gives the Government of Panama a deadline of 18 months to complete a full audit of all current software, deleting any pirated software or software unaccounted for by valid license agreements. According to the decree, the Government of Panama has an additional 18 months, or no more than three years total, to finalize negotiations with software producers for the full legalization of all government entities. Panamanian officials have given assurances that they will establish and implement a rigorous action plan so that this work can be completed well before the actual deadlines. Patents Panama's Industrial Property Law provides 20 years of patent protection from the date of filing. Pharmaceutical patents are granted for only 15 years, but can be renewed for an additional ten years, if the patent owner licenses a national company (minimum of 30% Panamanian ownership) to exploit the patent. The Industrial Property Law provides specific protection for trade secrets. 344 Trademarks Law 35 provides trademark protection, simplifies the process of registering trademarks and makes them renewable for ten-year periods. The law's most important feature is the granting of ex-officio authority to government agencies to conduct investigations and to seize materials suspected of being counterfeited. Decrees 123 of November 1996 and 79 of August 1997 specify the procedures to be followed by Customs and CFZ officials in conducting investigations and confiscating merchandise. In February 1997, the Customs Directorate created a special office for IPR enforcement, followed by a similar office created by the CFZ in March 1998. The Trademark Registration Office has undertaken significant modernization with a searchable computerized database of registered trademarks that is open to the public. INVESTMENT BARRIERS Panama maintains an open investment regime. Over the years the country has focused on bolstering its reputation as an international trading, banking, and services center. Panama recently completed an agreement with the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), a U.S. government finance and insurance agency. Previously, Panamanian statutes forbidding foreign government ownership of Panamanian territory had limited OPIC programs. The new agreement allows OPIC to operate in full. Since embracing OPIC, however, the current Government of Panama has adopted a disconcerting attitude toward foreign investors. A number of U.S. firms in Panama that are closely regulated by, or hold concessions from, the Government of Panama have encountered a lack of cooperation and even antagonism from certain officials. Investment disputes involving U.S. firms have arisen from Government of Panama actions, including conflicting contracts the Government of Panama has entered into with different firms. In such cases, the Government of FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS PANAMA Panama has frequently been unwilling to indemnify injured parties. In accordance with the terms of the US-Panama Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT), Panama places no restrictions on the nationality of senior management. Panama does restrict foreign nationals to 10 percent of the blue-collar work force, however, and specialized or technical foreign workers may number no more than 15 percent of all employees in a business. A revision of the labor code to ease restrictions on companies for dismissing employees was passed in the general assembly in 1995. government procurement and, at the municipal level, in obtaining local construction permits and the like. This issue is clearly a serious concern for representatives of U.S. firms already located in Panama. Finally, the new Government of Panama's ambiguous policies on trade matters present deep concerns for investors. Sudden changes in product restrictions, waiting periods, and tariff regimes with little or no notice to exporters have raised particular concerns. In July 1998, the government passed legislation aimed at protecting new investment in Panama. It guarantees that investors will have no restrictions on capital and dividend repatriation, foreign exchange use and disposal of production within a limited number of sectors in the economy. The spirit of the law is that for ten years, investors will not suffer any deterioration of the conditions prevailing at the time the investment is made. The guarantees are related to new laws affecting fiscal, customs, and labor regimes, that may be enacted in the future. TRADE RESTRICTIONS AFFECTING ELECTRONIC COMMERCE The U.S. Government is not aware of any existing tariff or non-tariff measures, burdensome or discriminatory regulations, or discriminatory taxation affecting electronic commerce. The Government of Panama has drafted e-commerce legislation that would, if passed, allow binding digital signatures and provide the legal framework for e-commerce. OTHER BARRIERS The judicial system can pose a problem for investors due to poorly trained personnel, huge case backlogs and a lack of independence from political influence. In addition, corruption persists, not only in the judicial system, but also in FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS 345