Preliminary: Please Cite with Authors’ Permission Only. Is NAFTA Polarizing México?

advertisement

Preliminary: Please Cite with Authors’ Permission Only.

Is NAFTA Polarizing México?

or Existe También el Sur?

Spatial Dimensions of Mexico’s Post-Liberalization Growth*

Patricio Aroca

Universidad Católica Del Norte

Antofagasta, Chile

Mariano Bosch

World Bank

William F. Maloney

World Bank

January 2003

Abstract: Standard parametric tests of convergence cannot capture

whether the increased dispersion among state incomes is due to a

steepening gradient between north and south, a few hot states randomly

distributed, or as an intermediate position, the emergence of

convergence clubs. This paper tests for spatial dependency in income

levels and growth rates before and after the trade liberalization of 1985.

Looking at levels of income per capita, we clearly identify a “South,”

but there is no “North” or “Center.” Beyond the frontline states on the

US border, we immediately enter an area as poor as the South and

incomes in the central zone itself are almost randomly distributed

geographically. Growth shows little evidence of spatial dependency in

any period: There is only weak evidence of a South and none of a North.

A strong co-movement of Chiapas and Oaxaca emerged in the 1995-00

period, but it had little historical precedent and whether it will continue

cannot be foreseen.

*

Our thanks to Daniel Lederman, Miguel Messmacher, and Raymond Robertson for helpful discussions. We

also thank Gabriel Victorio Montes Rojas for extraordinarily patient research assistance.

el norte es el que ordena…pero..

con su esperanza dura,

el sur también existe1

Benedetti.

I. Introduction

The 15 years beginning with Mexico’s dramatic unilateral trade liberalization in 1985

and including the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) have seen increasing

divergence of per capita incomes among Mexican states. Measures of sigma convergence

show a decrease in dispersion from 1970 to 1985, and then a sharp reversion to above

previous levels of inequality after 1989. A growing number of studies using traditional beta

convergence analysis,2 find at minimum a slowdown of convergence, and most divergence

(Juan-Ramon and Rivera Batiz 1996, Esquivel 1999, Messmacher 2000, Cermeño 2001,

Esquivel and Messmacher 2002, Chiquiar 2002). These findings raise the concern that trade

liberalization will lead to the polarization of the Mexican economy: the northern states may

industrialize and become increasingly integrated with the US, while the southern states will

remain “south” in Benedetti’s sense of “backward,” dependent, and forgotten. As evidence

in this direction, Hanson (1997) finds that after liberalization wages, which once decreased

with the distance from the national capital in the center, now decrease with the distance from

the border.

But a steeper North-South gradient where growth dynamism at its greatest near the

border is only one possibility scenario consistent with observed income divergence. A few

relatively high flying states could drive up inequality with no geographical pattern or as an

intermediate position, we may find multiple “convergence clubs” of states sharing spillovers

and common income levels and growth rates with little obvious geographical relationship

with the US.

This paper employs recent advances in spatial analysis to ask whether it makes any

sense to talk about a “north” or “south” or whether in fact the patterns of dynamism in

Mexico are geographically independent. Sigma, and Beta convergence approaches offer

point estimates of the central tendency of the data toward convergence or divergence.

1

Roughly translated from Benedetti’s famous poem, “The north rules and orders, but with a resilient hardbitten

hope, the south also exists (endures)”

2

See Barro and Sala-i-Martin, 1995

1

However, as Quah (1993) notes, they obscure vast amounts of information on the dynamics

of relative income movements among states and do not shed light on the spatial dimensions

of growth. A substantial literature has followed his lead in constructing Markov transition

matrices which tabulate the probabilities of moving among a finite number of intervals of the

national income distribution and hence characterize the dynamic patterns of relative income

movements.3 Employing these techniques for Mexico, Garcia-Verdu (2002) again finds little

evidence of convergence in the post 1985 period.

One advantage of these transition matrices is that they can be conditioned on state

characteristics, including geographical location, to permit inference about spatial patterns of

income dynamics. However, as Bulli (2001) notes, there are problems associated with the

naïve discretization of the income distribution. Quah (1997) proposes letting the number go

to infinity and conducting inference from kernel density plots.4 We begin by constructing

these for Mexico before and after the period of trade liberalization. We then condition them

on spatial characteristics to offer a view of the geographical dimensions of Mexico’s growth

process and more particularly, the “shape” of the divergence process. We are interested in

knowing if there is evidence of “spatial correlation” or “dependence” where either income

levels or growth rates are correlated by geographical location.

To further investigate the patterns of spatial dependency and to assess whether, in

fact, the observed changes in the kernels are statistically significant,

we employ tests

introduced for analyzing finite Markov transition matrices, and introduce parametric

measures of spatial dependence common in the spatial statistics literature but only recently

applied to the study of economic growth.

II. Data

The Mexican National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Information (INEGI)

tabulates official income data for Mexican 32 states GDP for 1970,1975,1980,1985,1988,

and then annually for the period 1993-2000. We follow Esquivel (1999), in making several

corrections to this data. First, most oil is pumped from the states of Tabasco and Campeche,

but the attribution of oil revenues has changed without obvious cause over time. Though the

3

4

See, for example, Fingleton, 1999; Rey, 2001; Lopez-Bazo et al, 1999; Puga, 1999

For the methodology behind estimating these kernels, readers are referred to the original paper (Quah 1997).

2

revenues are in fact allocated to all states via a federal sharing formula, in some years they

were entirely attributed to Tabasco, and in others to Campeche. We tried to correct for this,

excluding the oil production as captured in the mineral production category of the state

accounts, but still found the resulting growth series to be too erratic and exaggerated to be

credible. We attribute this behavior to unresolved petroleum accounting issues since the

remaining 30 non oil producing states behave more reasonably.5 Though dropping these

states clearly implies losing some of the spatial story, we find it preferable than

contaminating the analysis with clearly unreliable series.

Following Esquivel (1999) we also corrected populations figures for Chiapas and

Oaxaca for years 1975, 1980, 1985, 1988 as the 1980 census, when compared to other

household census appears to have understated the state’s population induced distortions in

the GDP per capita.6.

Finally we have merged the state of Mexico with Mexico DF (Federal District), the

capital. The rationale for this aggregation stems from the fact that there exist strong labor

market linkages between these two states which may lead to an overstatement of the capital

city’s per capita growth rates. Due to the exorbitant housing prices in DF, it has become

common to live in the state of Mexico and commute to the District.7 This has led to reported

population in the Mexico DF has remaining stable over the last 20 years while the population

in the state of Mexico doubled. We run the analysis both with and without this aggregation

(results available on request) and, while the fundamental story does not change, the more

moderate growth behavior of the aggregated capital city we find more plausible and we

report those results.

In sum, we have 29 states measured at 5 year intervals with 3 observations before the

unilateral trade liberalization of 1985 and 3 after8. Table 1 and figures 1,2a and 2b present

5

In fact, the state of Chiapas also produces some very modest amounts of oil and we subtracted this off from

the state product series in 1975 and 1980.

6

Population figures for years 1975, 1980, 1985, 1988 for Chiapas and Oaxaca were extrapolated using yearly

population growth rates between 1970 and 1990. According to official figures, the mining production over GDP

for Chiapas went from 7.5% in 1970 to 18% in 1975 up to 45% in 1980 and back to 7% in 1985. Clearly, years

1975 and 1980 saw arbitrary assignments of oil production to Chiapas. We have corrected for this as to allow

the ratio mining production over GDP to be 7.5% for the outlier years .

7

We would like to thank Miguel Messmacher for this suggestion.

8

When estimating the stochastic kernels and the transition matrices the years 1970, 1975, 1980, 1985, 1988,

1993 and 1998 were used. We tried to keep the 5 year period interval and at the same time avoid the 1995 crisis

which would have distorted our results.

3

that data and suggest that in the year 2000 regional differences in Mexico were vast. The

GDP per capita of the poorest state, Oaxaca in the South was only 23% of the richest, Nuevo

Leon in the North. The southern states overall enjoy less than half of the GDP per capita than

their northern counterparts.

III. Non-Parametric Measures: Transition Matrices Kernel Density Plots

Simple plots of the distribution of income levels and growth rates (available on

request) confirm Juan Ramon and Rivera-Batiz (1996) findings of a concentration in the

period 1970-80 consistent with parametric convergence tests findings. However, from 1985

onwards a prominent right tail appears in both levels and growth rates suggesting that a

group of states have detached from the others. Such snap shots of the distribution can be

informative, but they hide important information, and in particular, how we get from one

snapshot to another. We can ask, for example, whether the outliers in the extreme right tails

in plots of the growth distribution are the same states who persistently show higher growth,

or whether over the longer term, the distribution is broadly symmetric with random states

sometimes experiencing extraordinary growth.

Figures 3a and 3b plot the stochastic kernel as well as its contour plots for levels of

per capita income for the 1970-85 and 1985-1998 periods respectively. Both plot present

state income relative to the country (“country-relative”) in time t on the Y axis and in time

t+5 on the X axis. The exact scale is used in both the pre and post-liberalization periods to

facilitate inference about changes in the variance of the kernels. The cross-hairs depict the

country average in period t and in t+5. A couple points merit highlighting.

First, if there were no movement at all among states, figures 3a and 3b would consist

of a plane along the 45 degrees line shown. The fact that states do shift relative position

gives the kernel its volume. Slicing the volume parallel to the X axis reveals the distribution

of states at each initial income five years later. Again, the advantage over the simple

distribution plots is precisely that we can see changes of position that might be hidden by

identical “snap shot” distributions. Slicing parallel to the XY plane generates contour plots

that show the relative probabilities of finding combinations of initial and final incomes.

4

Second, significant convergence would result in a rotation of the kernel toward the Y

axis. States with lower incomes in t would have higher relative incomes in t+5 and vice

versa. Divergence would lead to the reverse. For broad illustrative purposes, we introduce a

state label at the position corresponding to the average value for each state. This reference is

only approximate since the kernel is estimated three time points for the each state, but given

the revealed persistence in relative income levels, they are informative.

In fact, the most salient feature of both figures is the high persistence in the

distribution. The probability mass is mainly concentrated in the diagonal of the plot showing

that states did not significantly change their relative position. States located above the 45

degree line saw a worsening of its relative position over time and those below, an

improvement.

Though the persistency is clear, striking differences emerge between the pre and post

85 kernels. First, the single peaked kernel in figure 3a has become a double or even triple

peaked kernel suggesting the formation of convergence clubs over the post 85 period. Several

forces are at play driving this evolution. First, the bottom end of the distribution has become

more compressed around 0.70 of the NAI (National Average Income) suggesting

convergence toward the mean of the very poorest states. Second, above average states

converged towards 1.3 of the NAI depopulating the center of the distribution. Finally, the

states of Mexico, Nuevo Leon and Quintana Roo grew in income enough to have formed the

last peak of the distribution with incomes above 1.7 NAI.

Global Spatial Association and Spatial Clustering.

Quah identified a similar “twin peaks” phenomenon in the Kernel derived from a

international cross section of per capital incomes and found it to be geographically drivenregional clusters of poor countries were getting poorer, the agglomerations of rich countries

were getting richer. To use the kernel density plots to see if the same geographical patterns

are emerging in Mexico, instead of generating it as the probability distribution of income in

t, t+5, we replace t+5 with the income of the state relative to the average income of its

contiguous neighbors (“neighbor-relative”) in t. If the local and economy wide distributions

5

of income are similar, that is, there are no clusters of states with similar incomes, we would

find a concentration of probabilities along the main diagonal. If, on the other hand, poor

states are found with poor states and rich with rich, we should expect a rotation toward a

vertical line at unity- a country relative poor state will have the same income as its

neighborhood.

Figures 4a and 4b plot the spatially conditioned kernal density plots. Several points

merit attention. First, geography is not destiny in Mexico the way it appears to be globally.

Most of the probability mass is off the vertical line at 1 on the X axis and is in fact broadly

aligned along the 45 degree line. We do not find Quah’s dramatic convergence clubs of rich

and poor states. Prior to 1985 there is some rotation and compression of the upper mass that

suggests that, particularly among northern states of Baja California Norte, Baja California

Sur, Chihuahua and Tamaulipas there is a nascent convergence club in incomes. Poor

southern states are also found to be better off relative to their neighbors than they are relative

to the country. For example, Chiapas’ income is around 50% of the NAI but it is as rich as

its neighbors (neighbor relative income is roughly unity).

But there is also a group of states (for example Zacatecas, Tlaxacala, Michoacan,

Nuevo Leon) whose mass lies largely on the 45 degree line suggesting no spatial

dependency. This pattern is exacerbated after 1985 where we can observe some rotation

towards the 45 degree line indicating a reduced relationship between states and their

neighborhood incomes. Had the clusters been totally determined by space the three observed

peaks would have been aligned along the vertical line at unity on the X axis. However,

figure 4b is fairly similar to the multiple peaked unconditional kernel of figure 3b. A more

detailed inspection shows the lower end peak is formed by a mass of southern and central

states, only Veracruz, Chiapas and in lesser degree Oaxaca have neighborhood relative

incomes close to unity. The intermediate peak, mainly consists of the northern states of Baja

California Norte, Baja California Sur, Coahila and some successful central states such as

Queretaro. There is some evidence of convergence among the northwest US border states ,

due to the catching up of Chihuahua and the poor performance of Baja California Norte.

However, as the northern converge club strengthened, the second line of states did not follow

thereby reducing spatial correlation and driving the rotation of the kernel towards the 45

6

degree line. Finally the third peak could not be more spatially independent as it is formed by

Nuevo Leon, Mexico and Quintana Roo. One state from each extreme of the country.

Growth

Figures 5a-b present an exactly analogous set of exercises replacing levels of income

with growth (see annex for definitions)9. Here, alignment along the axis suggests persistence

in growth rates: a fast growing state today will be fast tomorrow. Two things emerge

strikingly from the pre and post 1985 kernels. The mass of probabilities seems to occupy the

four quadrants equally more or less equally: A state that grows fast today is as likely to grow

slow tomorrow as to grow fast again. This is not so surprising when we remember that in the

pre liberalization period many of the northern states had alternating high and low growth

rates due to the 1982 debt crisis which hit the most dynamic states hardest. The distribution

shows greater variance in the post liberalization period, but still does not show strong

persistence in growth rates. Where extreme values can be found in the northwest quadrant

the orientation of the central mass appears to have rotated more to be more parallel to the Y

axis than before.

Conditioning on neighborhood (figures 6a-b) suggests little in the way of growth

convergence clusters. The central mass is fairly tightly aligned along the 45 degree reference

in the pre 85 period. In the post- 85 period, the variance again seems to have tightened some,

but there is no sign of rotation.

IV. Parametric Measures of Spatial Dependence

This section builds on the previous kernel analysis in two ways. First, although there

are as yet no methods for testing whether two kernels differ between two time period, we

offer a first approximation by employing tools recently developed for analyzing their

underlying Markov process for the case of a finite number of intervals. Second, we go into

further detail on the few suggested patterns of spatial dependence by employing techniques

common in the spatial statistics literature but only recently applied to the study of economic

growth (references).

9

In this case we did not referenced the states generating the mass of probabilities as the growth rates did not

show any persistency over time so the period averages would me meaningless.

7

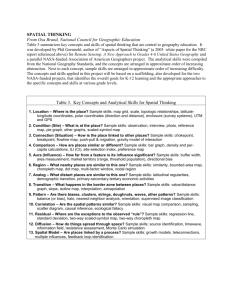

Testing for structural break in income dynamics

To test for whether the stochastic kernels for the pre and the post liberalization period

are, in fact, statistically significant, we generate standard double entry transition matrices.

The income distribution has been divided in 5 different intervals relative to the mean for the

entire time span and the pre and post liberalisation period. Each i,j entry of the matrix

represents the probability of transiting from income state i to income state j in a five year

period time10. Following Quah we discritize the income distribution in quintiles.

Similar to its graphical counterparts the transition matrices show a high degree of

persistence as suggested by the high probabilities of remaining in the same interval tabulated

along the main diagonal of the matrix. For instance, the probability of a state in interval 1

being found in that same interval in five years was 80% prior to 1985 and 93% after 1985.

This is preliminary evidence that, in fact, the transition matrices do differ between the two

periods in ways supportive of the beta convergence findings of increased dispersion after

1985. States in quintile one and two were able to move upwards in the distribution with

probability 7% and 5% respectively in the post 1985 period against 20% and 29% in the

previous time span suggesting that the increased dispersion was caused by a stagnation of the

poorer states. Following Bickenback and Boden (2001), we construct chi square statistics

tests for structural break in the matrix, both at the individual interval level and for the

matrices as a whole.

The test for our two sub-samples is based on a Q statistic

Qi =

∑n

j∈Bi

( pˆ i j (1970−85) − pˆ ij (1985−98) ) 2

i

pˆ ij (1985−98)

~ χ 2 ( Bi − 1)

Bi = { j : pˆ ij (1985−98) > 0}

10

The asymtotically imbiased and normally distributed Maximun likelihood estimator of

pij is determined by

pˆ ij = nij / ∑ j nij , where nij is the number of transitions from income class i to income class j over a period

of time.

8

Where p̂i j is the probability for a state to transit from income interval i to income interval j

For the whole matrix, the test is simply

Q = ∑ Qi

i

The Q statistics, suggest that the matrices are statistically different from each other, at the 1%

level and the main source of dissimilarity as noted before can be found in the poor income

intervals states (table 2). Prior to 1985, poor states had greater chances to move upwards in

the income distribution generating the usual finding of convergence over this period of time.

This is hinted in the kernels by the fact that the poor states are clearly below the 45 degree in

the pre-liberalization period (2a) and on or above it in the post liberalization period (2b).

Parametric measures of spatial association

The spatial econometrics literature offers several techniques heretofore little used in

the growth literature to more closely examine the dynamics suggested in the kernel density

plots.

The first measure of spatial dependence is Moran’s I statistic (the Global Moran)

which is the spatial analogue to the Durbin Watson statistic in time series (see Anselin 1988

and 1995). This is calculated for each period t as

n

It =

n

∑∑ w z z

n

S

i =1 j =1

n

ij i

∑z

i =1

j

, ∀ all t = 1,2,..., T

2

i

where n is the number of states; wij are the elements of a binary contiguity matrix W11(nxn),

taking the value 1 if states i and j share a common border and 0 if they do not; S is the sum of

all the elements of W; and zi and zj are normalized12 vectors of the log of per capita GDP of

states i and j respectively. Positive (clustering of similar values) spatial dependence, whereas

negative spatial correlation (clustering of different values). Statistical significance can be

11

Distance based matrices have been also employed giving similar results to the above presented.

The zi = ln(GDPit /GDPt) denotes the logarithm of the Gross Domestic Product per capita of region i in period

t, (GDPit), normalized by the sample mean of the same variable, GDPt (De la Fuente, 1997).

12

9

tested comparing the Moran’s I statistic with its theoretical mean and using a normal

approximation.

Figures 7a and b plot Moran’s I normal standardized values for the period 1970-2000

for both levels and growth rates, as well as the standard deviation of the GDP per capita for

the same period as a measure of sigma convergence. What is immediately clear is that,

viewing Mexico as a whole, spatial dependence in income levels has increased along with the

sigma divergence after a period when both had fallen. The correlation between both variables

is 0.85. By the year 2000 the global measure of spatial concentration is similar to the 70’s

levels. In levels, the relatively subtle indications of spatial dependence suggested in the

Kernels emerge as statistically significant in the Moran test.

However, in growth rates, only the period 1970-80 saw any traces of spatial

association. It is no longer the case that fast growing states are found next to fast, and slow

next to slow. In growth terms, there has been a despatialization of Mexico, far predating the

mid-1980s reforms that arguably has not been significantly reversed. The insignificance of

the Moran in growth rates is consistent with the very diffuse patterns observed in the kernels

for both periods.

The global Moran may, however, conceal patterns of comovement in particular

growth poles or convergence clubs. These can be more easily detected by the “Local” Moran

which calculates the Moran between an individual state and its spatial lag- the states which

share a common border:

Ii =

z i ∑ wij z j

j

∑z

2

i

/n

The local Moran can be interpreted as an indicator of spatial clustering, either of positive

correlation or negative where the null hypothesis is no spatial dependence. Local clusters are

identified where the statistic is significantly different from zero. Since the distribution of the

statistic is usually unknown, Anselin (1995) suggests a Montecarlo-style method to generate

it, consisting of the conditional randomization of the vector zj.13 That is, Moran statistics are

calculated between state i and a large number of hypothetical “neighborhoods” constructed as

13

It is conditional in the sense that zi remains fixed. The reasoning behind the randomization procedure lies in

the need to assess the statistical significance of the linkage of one region to its neighbors.

10

random permutations of states drawn from the entire sample. Then, the true neighborhood

Moran is compared against this distribution.

We present the local Moran statistics in several different ways. First, the maps in

figures 8a and 8b show the geographical distribution of significant local Moran’s for both the

10% and 5% levels for the years 1970 and 2000, the endpoints of our sample. Second, the

Moran scatterplots accompanying the maps graph the level of income of the state against that

of its spatial lag for the same period as a way of showing global spatial correlation. Clearly,

a significant positive slope suggests that rich states are found among rich (quadrant 1) and

poor among poor (quadrant 3). Quadrants 2 and 4 represent cases where rich states are found

among poor, or poor among rich respectively.

In fact this is a less efficient and

comprehensive way of presenting the information in the kernels but one which allows a

clearer view of the relative position of the states. Finally, table 3 shows significance levels

and signs of the Moran statistics at 5 year intervals across the sample to offer greater detail

across time than is possible with the graphs.

The data suggest that spatial dependency in levels is not new. Even in 1970, there

was a cluster of poor states around Oaxaca, Guerrero, Puebla, Chiapas and Guerrero

corresponding to the traditional “Southern States” that appears strongly in the maps and in

quadrant 3 of the scatter plots and table 3 suggests that this relationship has been getting

stronger across time.

Baja California Norte and Baja California Sur, and Sonora appear in the quadrant 1 as

well-off states in better-off neighborhoods, and hence might be seen as a well-off

convergence cluster located in the north of the country along the US border. However, these

correlations seem to slowly disappear by the beginning of the 1990’s and the North, as a

spatial construct, vanishes. This is partly due to the fact that, as the figures 2a and 2b

suggest, the frontline states are better off, but the next tier- Durango, Sinaloa, Zacatecas and

San Luis Potosi are poor and this gap has been getting larger thereby diluting the spatial

correlation. The higher income of the frontline states has not spilled over much to the next

line. This pattern we noted from the kernel in figure 4b where the rotation towards the 45

degree line indicates this widening gap between the north and the second line of states.

Nor in the center do we find much in the way of convergence clusters. Most of the

Central states are located in quadrants 2 and 4 almost suggesting a downward sloping line (if

11

we abstract from the outliers) suggesting a tendency that rich states are found among poor

and vice versa. The greater variance in income per capita of this region (see table 1) does not

translated into spatial dependency: poor states such as Zacatecas, Michoacan, Hidalgo,

Nayarit and rich states such as Mexico, Aguascalientes and Queretano share the same

neighborhood. Consequently, we do not find any significant Moran statistics in this area for

any of the periods, with the exception on the negative values associated with Jalisco and

Mexico/DF indicating that this two states are well-off states surrounded by poor neighbors.

At this point these results suggest that the Mexico/DF agglomeration has not pulled along its

neighbors. In sum, the South exists, but there is no longer a North and there never was a

Center.

Growth appears even less spatially dependent in figure 9a and b, consistent with our

previous findings in the kernels. When we study long periods of growth using the entire pre

and post liberalization samples, only two clusters emerge. In the early period, we find

positive co movements among Baja California Norte, Baja California Sur, and Sonora with

their neighbors in the quadrant 3 of low growth states among low growth states. Chiapas

Oaxaca and Veracruz replicate this behavior in the post trade liberalization period .

Additionally, the Mexico/DF aggregation significantly under performs in the early period in

a time when its neighborhood was doing much better. These findings are consistent with the

income convergence observed before liberalization and the divergence after.

Looking more finely with five year periods, no significant patterns seem to survive

over time. Hidalgo and San Luis de Potosi constitute a high growth cluster by the end of the

70’s and a similar pattern emerges with the two states in the Yucatan peninsula in the 70’s.

Morelos showed local spatial instability and early 90’s respectively. Finally, Puebla

outperforms its neighbors southern states in the late 90’s.

Table 3 also suggests that the low growth cluster found in the north for the overall

period 70-85 may be due to a common vulnerability of the more industrial states to the oil

crisis and the US recession. Analogously, the southern cluster of low growth result appears

to be driven by the strongly significant Moran statistics found in both Chiapas and Oaxaca in

95-00. In both cases the related states grew below average for the country. That said, there

is not a consistent pattern of association of Chiapas with its neighbors and it is probably

premature to assert that, in growth terms, there is a South and there is pretty clearly no North.

12

Its also notable that the Mexico/DF aggregation never positively commoves with its

neighbors, nor do such higher performance middle states such as Queretaro, Jalisco or

Guanajuato.

V. Conclusions.

This paper employs several recent techniques from the spatial statistics literature to

investigate the geographical dimensions state income divergence in Mexico. The Moran

statistics and the kernel density plots tell us a consistent story: there is no gentle growth

driving gradient sloping down from the US and losing steam just before Chiapas. In levels,

the South exists, but there is no longer a North and there never was a Center.

This

conclusion, again, must be tempered by the finding that if we define the northern

neighborhood to only include the border states, we do find stronger evidence of a

convergence cluster. But the discrete income cliff after the front line after which a virtually

random pattern emerges interrupted only by the group of 3 or 4 Southern states suggests that

proximity to the North is not the exclusive or even overriding determinant of high income

levels. This is also supported by the findings that growth appears to be essentially randomly

distributed with the exception of a potential (low) growth cluster among Chiapas, Veracruz

and Oaxaca that is not shared with other states far from the border. These states are being

left behind, but exclusion from the benefits of NAFTA due the lack of proximity to the US

does not seem to be the cause.

13

References

Anselin, L. 1988. Spatial Econometrics: Methods and Models. Kluwer. Dordrecht.

Anselin, L. 1995 “'Local Indicators of spatial association-LISA.” Geographical Analysis 27:

93-115.

Barro, R. J. and Sala i Martin, X. 1995. Economic Growth . McGraw-Hill.

Bickenbach, F. and Bode E. .2001. “Markov or Not Markov”-This Should Be a Question”/

Kiel Institute of World Economics working paper series No 1086.

Bulli, S. 2001. “Distribution Dynamics and Cross-Country Convergence: A New Approach.”

Scottish Journal of Political Economy 48 (2): 226-243.

Cermeño, R. 2001. “Decrecimiento y convergencia de los estados mexicanos: Un analisis de

panel”. El Trimestre Economico 28(4): 603-629

Chiquiar Cikurel, D. 2002. “Why Mexico’s regional income convergence broke down ?”

Paper presented at the Conference on Spatial Inequality in Latin America. November 1-3.

Cholula, Mexico

Esquivel, G. 1999. “Convergencia Regional en Mexico, 1940-95”, El Trimestre Económico

LXVI (4) 264: 725-761.

Esquivel, G, and Messmacher, M. 2002. “ Sources of (non) Convergence in Mexico”. IBRD

mimeo. Chief Economist Office for Latin America. Washington D.C.

Fingleton, B. 1999. ''Estimates of Time to Economic Convergence: An Analysis of Regions

of the European Union'.' International Regional Science Review 22(1):5-34.

Fuente , A de la. 1997. "The empirics of growth and convergence: a selective review."

Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 21(1): 23-74.

Hanson, G. 1997. “Increasing Returns, Trade, and the Regional Structure of Wages.”

Economic Journal 107: 113-133

Juan Ramon, V.H., and Rivera-Batíz, A. 1996.”Regional growth in México:1970-1993”. IMF

working paper WP/96/92 .

Lopez-Bazo, E., Vayà, E., Mora, A.J. and Suriñach, J. 1999. ''Regional economic dynamics

and convergence in the European Union.'' Annals of Regional Science 33: 343-370.

Messmacher, M. 2000. “Desigualdad Regional en México. El Efecto del TLCAN y Otras

Reformas Estructurales”. Working Paper No 2000-4. Dirección General de Investigación

Económica. Banco de México.

Puga, D. 1999. “The Rise and Fall of Regional Inequalities.” European Economic Review 43

(2): 303-334

Quah, D. T. 1993, ''Empirical cross-section dynamics in economic growth.” European

Economic Review 37; 427-443.

Quah, D. T. 1997 ''Empirics for growth and distribution: Stratification, polarization and

convergence clubs''. Journal of Economic Growth 2(1): 27-59.

Rey, S. J. 2001. “Spatial Empirics for Economic Growth and Convergence”, Geographical

Analysis 33(3): 195-214.

14

Annex I: Conditioning of Kernels.

Definitions:

yit the income per capita of state i in year t,

yt the national average income per capita in year t,

ywt th average income per capita of the spatial lag in year t.

Figures 9 a:

Kernels generated using three growth spans of 5 years each before and after 1985:

yit + s

y

t+s y

it

y

t

− 1 conditioned to

yit

y

t y −1

it − s

y

t −s

yit

y

t y − 1 conditioned to

it − s

yt − s

yit

y

wt y − 1

it − s

ywt − s

Figures 9b:

15

Table 1. Mexican 2000 GDP per capita by state, constant pesos 1993

State

Baja California

BC

CO

Coahuila

CU

Chihuahua

Nuevo León

NL

SO

Sonora

Tamaulipas

TA

BCs Baja California Sur

DU

Durango

San Luis Potosí

SL

SI

Sinaloa

ZA

Zacatecas

AG

Aguascalientes

CL

Colima

GU

Guanajuato

Hidalgo

HI

JA

Jalisco

Mexico and DF

MX

MI

Michoacán

Morelos

MO

NA

Nayarit

Querétaro

QU

CH

Chiapas

GE

Guerrero

OA

Oaxaca

Puebla

PU

TL

Tlaxcala

Veracruz

VC

QI

YU

Quintana Roo

Yucatán

CA

DF

MX

TB

Campeche

Distrito Federal

México

Tabasco

Total Nacional

Region

North

Central-North

Central

South

Yucatan

Peninsula

Not in the

sample

Population GDP millions

(Thousands

of pesos

GDP per

capita

2,487

2,298

3,053

3,834

2,217

2,753

424

1,449

2,299

2,537

1,354

944

543

4,663

2,236

6,322

21,702

3,986

1,555

920

1,404

3,921

3,080

3,439

5,077

963

6,909

48,157

45,976

66,009

101,689

40,458

44,793

7,906

18,001

25,505

30,074

11,314

16,958

8,244

48,373

21,013

94,653

493,328

34,921

20,733

8,255

25,401

25,070

24,149

21,797

50,601

7,994

60,767

19,361

20,006

21,622

26,522

18,249

16,269

18,644

12,426

11,092

11,855

8,358

17,959

15,193

10,374

9,400

14,972

22,732

8,762

13,331

8,971

18,088

6,394

7,842

6,339

9,967

8,304

8,795

875

1,658

19,555

19,807

22,350

11,945

15,924

334,770

158,558

17,301

1,441,500

23,056

38,903

12,107

9,145

14,787

691

8,605

13,097

1,892

97,483

GDP per

Standard

capita by

Deviation/

region

Mean

20,855

0.17

11,510

0.30

17,434

0.34

8,140

0.18

15,539

0.43

14,787

0.40

16

Figure 1: Mexican Regional Map

Baja California Norte

Sonora

Chihuahua

Coahuila De Zaragoza

Nuevo Leon

Tamaulipas

Zacatecas

Aguascalientes

Durango

San Luis Potosi

Sinaloa

Baja California Sur

Guanajuato

Nayarit

Hidalgo

Jalisco

Tlaxcala

Colima

N

W

S

Puebla

Queretaro de Arteaga

Michoacan de Ocampo

Mexico

Distrito Federal

E

Morelos

Guerrero

700

Yucatan

Veracruz-Llave

Oaxaca

0

Quintana Roo

Chiapas

700

Figure 2a: Mexican states relative GDP per capita: 1970

1400 Miles

Figure 2b: Mexican states relative GDP per capita: 2000

N

W

E

S

N

W

E

S

Mx30b.shp

0.427

0.609

0.802

1.051

1.354

Mx30b.shp

0.352 - 0.584

0.584 - 0.715

0.715 - 0.856

0.856 - 1.201

1.201 - 1.924

600

600

0

600

- 0.609

- 0.802

- 1.051

- 1.354

- 2.494

0

600

1200 Mile s

1200 Miles

17

Figure 3a: Kernel Density Plots, Levels, Unconditioned:1970-1985

2.5

2

Country relative, period t

NL

MX

BC

BCs

1.5

SOCO

QI

T AJA

CU

CL

SI QU

MO

AG

VC

YU

NA

GU DU

PU

HI

MISL

GE T L

ZC

CH

1

0.5

0

OA

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

Country relative, period t+5

Figure 3b: Kernel Density Plots, Levels, Unconditioned:1985-1998)

2.5

Country relative, period t

2

NL

MX QI

1.5

1

CH

OA

0.5

0

0

0.5

CLQU

JA

TA

MO AG

SI

DU

SL

YU

NA

VC

HI

GU

TLPU

ZC

GE

MI

1

BC

BCs

SO CO

CU

1.5

2

2.5

Country relative, period t+5

18

Figure 4a: Kernel Density Plots, Levels, Conditional on Spatial Lag (Neighbors):1970-1985

3

2.5

2

NL

Country relative

MX

BC

BCs

SO

1.5

TA

CU CL

QU

SI MOAG

NA

VC

YU DU

GU

SL HI PU

TL GE

MI

CH

ZC

OA

1

0.5

0

0

0.5

1

CO

QI

JA

1.5

Neighbor relative

2

2.5

3

Figure 4b: Kernel Density Plots, Levels, Conditional on Spatial Lag (Neighbors):1985-1998

3

Country relative

2.5

2

NL

QI

1.5

MX

BC CO

BCs

SOCU

QU

CL

TA

AG JA

MO

SI DU

NA

YU

SL

HI GU VC

ZC TL PU

MI GE

CH

OA

1

0.5

0

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

Neighbor relative

19

Figure 5a: Kernel Density Plots, Growth, Unconditioned: 1970-1985

0.1

0.08

Country relative, period t

0.06

0.04

0.02

0

-0.02

-0.04

-0.06

-0.08

-0.1

-0.1

-0.08

-0.06

-0.04

-0.02

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

Country relative, period t+5

Figure 5b: Kernel Density Plots, Growth, Unconditioned: 1985-1998

0.1

0.08

Country relative, period t

0.06

0.04

0.02

0

-0.02

-0.04

-0.06

-0.08

-0.1

-0.1

-0.08

-0.06

-0.04

-0.02

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

Country relative, period t+5

20

Figure 6a: Kernel Density Plots, Growth, Conditional on Spatial Lag (Neighbors):1970-1985

0.1

0.08

0.06

Country relative

0.04

0.02

0

-0.02

-0.04

-0.06

-0.08

-0.1

-0.1

-0.08

-0.06 -0.04 -0.02

0

0.02

Neighbor relative

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

Figure 6b: Kernel Density Plots, Growth, Conditional on Spatial Lag (Neighbors):1985-1998

0.1

0.08

0.06

Country relative

0.04

0.02

0

-0.02

-0.04

-0.06

-0.08

-0.1

-0.1

-0.08

-0.06 -0.04

-0.02

0

0.02

Neighbor relative

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.1

21

Table 2. Transition Matrices 1970-1998

Transition Matrix 1970-1998

Number

1

2

35

1 0.86

0.14

35

2 0.17

0.69

35

3 0.00

0.14

35

4 0.00

0.00

34

5 0.00

0.00

3

0.00

0.14

0.77

0.03

0.00

4

0.00

0.00

0.09

0.80

0.18

5

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.17

0.82

Transition Matrix 1970-1985

1

20

1 0.80

14

2 0.07

21

3 0.00

13

4 0.00

19

5 0.00

2

0.20

0.64

0.14

0.00

0.00

3

0.00

0.29

0.76

0.00

0.00

4

0.00

0.00

0.10

0.92

0.21

5

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.08

0.79

Transtion Matrix 1985-1998

1

15

1 0.93

21

2 0.24

14

3 0.00

22

4 0.00

15

5 0.00

2

0.07

0.71

0.14

0.00

0.00

3

0.00

0.05

0.79

0.05

0.00

4

0.00

0.00

0.07

0.73

0.13

5

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.23

0.87

d.f Q-statistic P-value

Ho:

pˆ i j (1985−98) = pˆ i j (1970−85) | i = 1

1

5.71

0.02

Ho:

pˆ i j (1985−98) = pˆ i j (1970−85) | i = 2

2

18.40

0.00

ˆ i j (1985−98) = pˆ i j (1970 −85) | i = 3

Ho: p

2

0.18

0.91

Ho:

pˆ i j (1985−98) = pˆ i j (1970−85) | i = 4

2

2.57

0.28

Ho:

pˆ i j (1985−98) = pˆ i j (1970 −85) | i = 5

1

0.98

0.32

Ho:

pˆ i j (1985−98) = pˆ i j (1970−85) ∀i

8

27.85

0.00

22

Figure 7a: Global Moran’s I (levels) and Standard deviation 1970-2000

2.8

0.45

2.6

0.4

2.4

0.35

2.2

0.3

2

0.25

1.8

0.2

1.6

0.15

1.4

0.1

1.2

0.05

1

1970

0

1975

1980

Moran's I

1985

1988

1993

1998

2000

Standard Deviation

Figure 7b: Global Moran’s I (growth rates)

5

4.5

4

3.5

3

2.5

2

1.5

1

0.5

0

1970-1975 1975-1980 1980-1985 1985-1988 1988-1993 1993-1998

23

Figure 8a: Significance of Local Moran for GDP per capita 1970: Map and Moran Scatterplot

Significance level

5%

10%

2.5

2

BCs

BC

1.5

1

SO

Spatial Lag

0.5

N

MI

ZC

0

SL

TL

HI

GE

-0.5

W

YU

OA

E

CH

MO

DU

NA AG

CL

QU

PU

GU

VC

SI

CU

TA

CO

NL

QI

JA

MX

-1

S

60 0

0

6 00

-1.5

1 200 Mi le s

-2

-2.5

-2.5

-2

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

Relative Gross Domestic Product Per Capita:1970

Figure 8b: Significance of Local Moran for GDP per capita 2000: Map and Moran Scatterplot

Significance level

5%

2.5

10%

2

1.5

YU

BCs

Spatial Lag

1

N

W

SO

0.5

ZC

SL

NA

CO

TA

DU

MO

HI

GE

-0.5

SI

MI

TL

0

BC

JA

GU

PU

CL

-0.5

0

QU

CU

NL

QI

AG

MX

VC

E

OA

-1

CH

S

-1.5

60 0

0

6 00

1 200 Mi le s

-2

-2.5

-2.5

-2

-1.5

-1

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

Relative Gross Domestic Product Per Capita:2000

24

Figure 9a: Significance of Local Moran for Growth of GDP per capita 1970-1985: Map and Moran Scatterplot

Significance level

5%

10%

2.5

2

1.5

Spatial Lag

1

N

W

E

0

SI

-0.5

0

6 00

HI

CL

DU

CH

OA

QU

TL

BC

-1.5

12 00 Mi le s

GU

PU

CO

JA MI GE

NL

AG

SL

ZC

NA

TA MO

CU

QI

SO

BCs

-1

S

600

YU

VC

MX

0.5

-2

-2.5

-2.5

-2

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

Relative Gross Domestic Product Per Capita Growth:1970-1985

Figure 9b: Significance of Local Moran for Growth of GDP per capita 1985-2000: Map and Moran Scatterplot

Significance level

5%

10%

2.5

2

1.5

YU

1

Spatial Lag

QI

N

W

E

S

600

0

6 00

1200 Mi le s

SO

0.5

JA

0

TL

NA

VC

-0.5

-1

CO

NL

DU ZC BC

MI SL QU

CL GU

BCs

GE SI

MO

MX

HI

TA

CU

AG

PU

OA

CH

-1.5

-2

-2.5

-2.5

-2

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

Relative Gross Domestic Product Per Capita Growth:1985-2000

25

State

Baja California

Coahuila

Chihuahua

Nuevo León

Sonora

Tamaulipas

Baja California Sur

Durango

San Luis Potosí

Sinaloa

Zacatecas

Aguascalientes

Colima

Guanajuato

Hidalgo

Jalisco

México

Michoacán

Morelos

Nayarit

Querétaro

Chiapas

Guerrero

Oaxaca

Puebla

Tlaxcala

Veracruz

Quintana Roo

Yucatán

70

++

Table 3. Significance of Local Moran Statistics : Levels and Growth

Levels

Growth

75

80

85

88

93

98 2000 70-75 75-80 80-85 85-88 88-93 93-98 95-00 70-85 85-00

+

+

+

+

+

+

++

++

++

++

+

++

+

++

+

++

--

--

-

-

-

+

-

-++

+

++

++

++

+

++

++

++

+

++

+

++

+

++

+

++

+

++

+

+

++

++

++

-

++

++

++

-

++

+

--

+

+

+

+

++

++

+

26