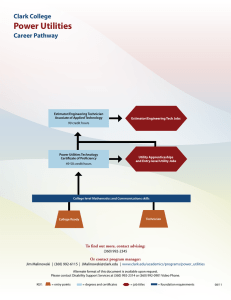

PLANNING GOVERNMENT by 1970 INCENTIVES

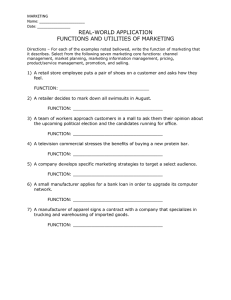

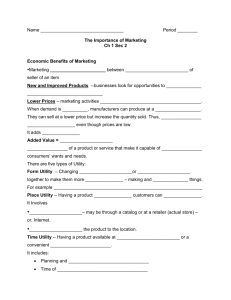

advertisement