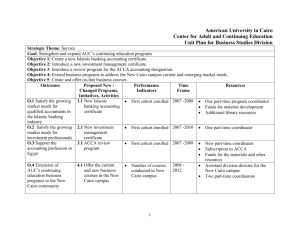

ISLAMIC A M, 1977

advertisement