Document 10466049

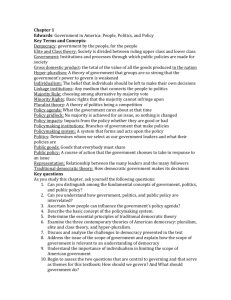

advertisement