Disappeared: Justice Denied in Mexico’s Guerrero State

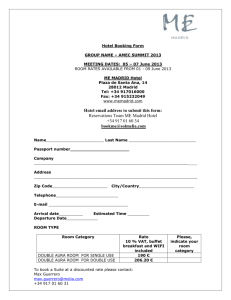

advertisement