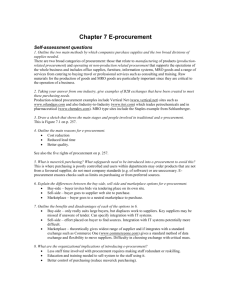

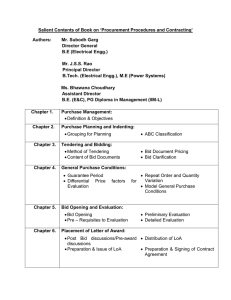

CHAPTER 5.

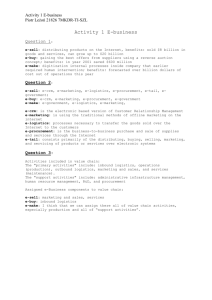

advertisement