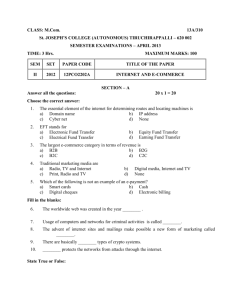

E-COMMERCE AND DEVELOPMENT

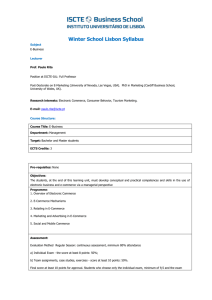

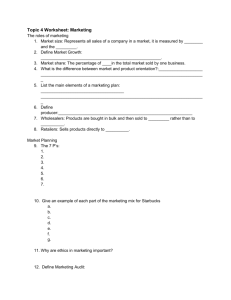

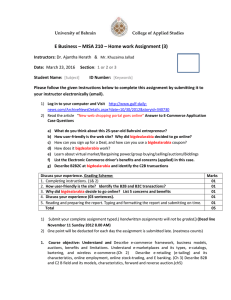

advertisement