Is the 2010 Affordable Care Act Minimum Standard to

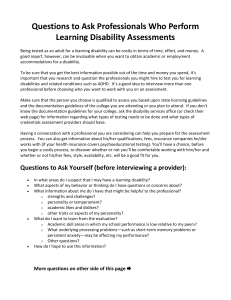

advertisement