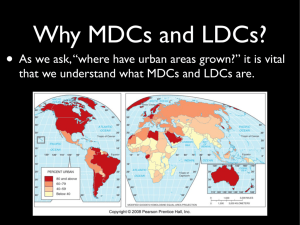

T L D C

advertisement