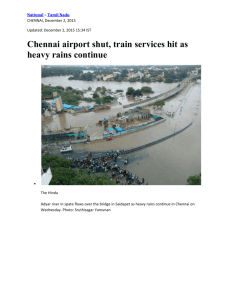

An Overview of the Medical Tourism Industry in Chennai, India

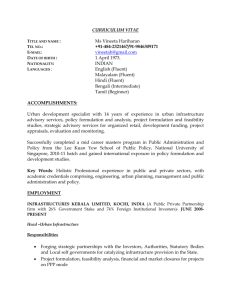

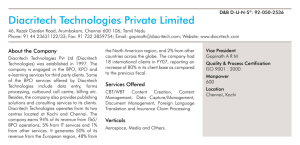

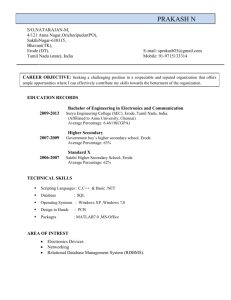

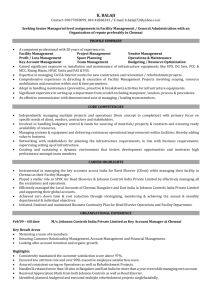

advertisement