Understanding Customer Reactions to Brokered Ultimatums: Applying Negotiation and Justice Theory

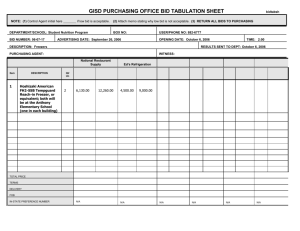

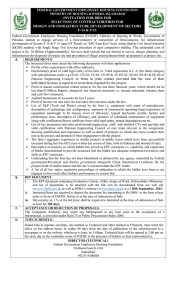

advertisement