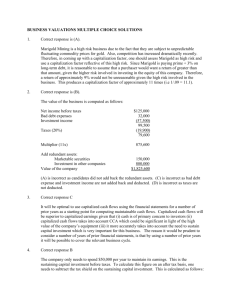

Accounting Research Center, Booth School of Business, University of Chicago

advertisement