LIFO Liquidations and Earnings Thresholds

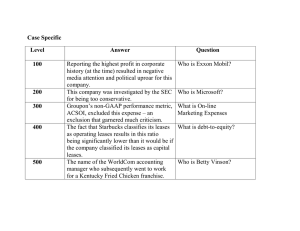

advertisement

LIFO Liquidations and Earnings Thresholds Cristi A. Gleason*, W. Bruce Johnson & Xiaoli Tian Tippie College of Business, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242 Preliminary and incomplete, please do not cite without permission. Draft: March 2010 We appreciate the invaluable research assistance provided by Monty Gupta and Rengarajan Narayanan. We also gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Thomson Financial for providing earnings forecast data (available through the Institutional Brokers Estimate System) as part of a broad academic program to encourage earnings expectations research. * Corresponding author: cristi-gleason@uiowa.edu, Tippie College of Business, 108 PBB, Iowa City, IA 52242-1994. Office (319) 335-1505. Fax (319) 335-1956. LIFO Liquidations and Earnings Thresholds Abstract This study investigates the use of LIFO liquidations to meet or beat earnings benchmarks. We find that the likelihood of a liquidation is higher for firms that would otherwise miss the consensus forecast than for firms that are already beating the consensus forecast. This result is incremental to controlling for the tax costs of liquidation and other factors predicted to partially explain managers’ inventory liquidation decisions.. The market response to unexpected earnings arising from liquidation gains is negative, relative to the overall response to unexpected earnings. However, the liquidation gain is positively associated with the announcement period return for firms that appear to have used the liquidation to beat earnings benchmarks. In contrast, firms that liquidated earnings for non-benchmark related reasons have no significant market response to the liquidation gain. One explanation for this result is that liquidations to beat benchmarks have less negative implications for future sales and profitability. 1. Introduction Widespread use of the last-in, first-out (LIFO) method of accounting for inventory in the United States extends over a nearly 70 year period. LIFO was first allowed for federal income tax purposes in 1939 although a few petroleum companies used it for shareholder reporting purposes prior to that date (Morse and Richardson 1983).1 A unique and well-known feature of the LIFO method is that end-of-period inventory purchase decisions have an immediate impact on taxable income and reported GAAP income. The larger are end-of-period inventory unit costs relative to those prevailing earlier in the year or in prior years subsequent to LIFO adoption, the greater the potential decrease in income from additional purchases and the greater the potential increase in income from deferring purchases. We focus on the ability of the LIFO inventory method to permit firms to manage quarterly earnings. LIFO liquidations, the term used to describe reductions in LIFO inventory quantities, trigger recognition of inventory holding gains during periods of rising unit costs. These liquidation holding gains increase gross profit and net income, although the increases are transitory and thus less persistent than other net income components. Our first research question asks whether LIFO liquidations contribute to firm’s earnings benchmark beating behavior. We draw on the earnings threshold literature (Burgstahler and Dichev 1999 and Degeorge et al. 1999, among others) and provide evidence on whether accretive liquidations are disproportionately more frequent among LIFO firms where reported quarterly EPS would have otherwise fallen short of analysts’ consensus forecasts. Prior research has examined the association between LIFO liquidation and changes in annual earnings, earnings variability, and proximity to debt covenants (Dhaliwal et al. 1994; 1 LIFO is not acceptable for income tax purposes in most foreign countries and is not permitted for financial reporting purposes under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). 1 Sweeney 1994; Hunt et al. 1996). Our interest is in better understanding the extent to which liquidations are used as an earnings management tool. We identify a sample of 1,204 quarterly LIFO liquidations from electronic text searches of firms’ 10-Q and 10-K financial reports and 8-K earnings press release filings for 1994 through 2007. LIFO liquidations are rarely mentioned in earnings press releases and are concentrated in the fourth fiscal quarter. A non-liquidation (control) sample is constructed by identifying firms with balance sheet LIFO reserves (i.e., unrecognized LIFO inventory holding gains) of at least two cents per share. For firms with relatively modest LIFO liquidations (between 0.5 and 10.0 cents per share), liquidation is more prevalent among firms that would otherwise miss the consensus quarterly EPS forecast. This result is incremental to controlling for the tax costs of liquidation and other factors (e.g., prior liquidations) predicted to partially explain managers’ inventory liquidation decisions. The distribution of LIFO firms’ earnings surprises exhibit the familiar discontinuity around the zero forecast error bin, so LIFO liquidation firms appear to be successful in managing earnings. We also examine the stock price response to earnings surprises when LIFO firms liquidate inventory during the quarter. Prior research (Stober 1986; Tse 1990) finds no evidence of a general market reaction to LIFO liquidations at either the annual earnings announcement or later 10-K filing date. We re-examine the question of whether investors spot and price the liquidation gains in earnings surprises using a large, timely sample of quarterly LIFO liquidations. In contrast to prior research, we find a significantly negative incremental market reaction to the liquidation gain at the earnings announcement. The net result is that investors appear to discern and discount the portion of the quarterly earnings surprise that is attributable to LIFO liquidation gain. At the same time, investors discount less (and in fact “reward”) those liquidations gains that enable firms to achieve the target EPS. One explanation for this finding is that liquidations motivated by EPS benchmark beating have less negative implications for future sales and profitability. 2 This study contributes to two distinct streams of prior research. Our research extends prior research on the specific accounting tools firms use to manage earnings (i.e., McNichols and Wilson 1988, Moehrle 2002, Dhaliwal, Gleason and Mills 2004, Hribar, Jenkins, Johnson 2006). We also extend earlier research on the determinants (Dhaliwal et al. 1994; Sweeney 1994; Hunt et al. 1996) and stock market impact (Stober 1986; Tse 1990) of LIFO liquidations. Our results have implications for regulators and market participants. Understanding the costs and benefits of permitting the LIFO inventory valuation method is also important for evaluating the impact of convergence with IFRS. 2. Background and Research Questions LIFO liquidations occur when inventory quantities in a LIFO “pool” are reduced. 2 If inventory costs are rising, the quantity reduction triggers accounting recognition of an unrealized inventory holding gain that increases reported earnings. 3 An identical holding gain is recognized for income tax purposes; so there is generally a tax cost associated with liquidation. 4 Firms are Neither GAAP nor Internal Revenue Service (IRS) regulations require that LIFO be used for all inventories when the method is elected. Situations for which the LIFO election scope does not encompass all inventories are referred to as “partial” or “selective” LIFO elections. Similar inventory items are often grouped together to establish separate LIFO pools, and several different methods for grouping inventory items into LIFO pools are allowed by the IRS in Reg. § 1.472-8(b), (c) & (d). Consequently, LIFO liquidation does not necessarily lead to an overall reduction in LIFO inventory balances. Companies may have more than one LIFO inventory pool, and it is possible that liquidation in one pool is more than offset by inventory quantity increases in another pool. 2 Beginning in 1974, SEC Regulation S-X, Rule 5-02.6 required firms that use LIFO to disclose the amount of the socalled LIFO Reserve, which is the difference between ending inventories as reported at LIFO cost and the “current cost” of ending inventories. This reserve amount represents the aggregate unrealized LIFO inventory holding gain as of the balance sheet date. 3 Internal Revenue Code § 472(c) and § 474(e) require a firm using LIFO for tax purposes to also use LIFO for financial reporting purposes. Consequently, LIFO liquidation gains nearly always increase both accounting earnings and taxable income. The specific tax consequences of LIFO liquidation depend on the firm’s tax status, however. For example, the tax cost of liquidation may be fully offset by net operating loss carry-forwards that would otherwise expire unused. 4 3 not required to recognize gains (or losses) from LIFO liquidations at interim reporting dates if inventory quantities will be replenished by year-end (APB Opinion No. 28, para 13). 5 There are two strands of existing LIFO liquidation research. One strand tests conjectures about the determinants of LIFO liquidation, emphasizing the trade-off between financial reporting benefits and tax costs. The other strand explores the share price response to recognized LIFO liquidation holding gains. 2.1 Determinants of LIFO Liquidations Drawing on a well developed literature on the economic incentives underlying accounting choices, prior research on the determinants of LIFO liquidation decisions has focused on three factors: income taxes, operational changes, and financial statement effects.6 LIFO firms liquidate inventories less frequently and in smaller magnitudes than do FIFO firms (Biddle 1980b; Davis, Kahn and Rozen 1984; Tse 1990), a result that suggests the tax costs of LIFO inventory reductions induce managers to avoid liquidation. Frankel and Trezvant (1994) also find that high tax-rate LIFO firms are more likely to purchase additional (“excess”) inventory at year-end compared to their low tax-rate LIFO counterparts or FIFO firms. This result suggests that high tax-rate LIFO firms incur operational inefficiencies—the added carrying costs of this excess inventory—to gain income tax reductions. Operational efficiencies may override income tax considerations when economic conditions change. The prevalence of LIFO liquidations in the early 1980s, for example, is attributed to sluggish demand in a recessionary economy, coupled with unusually high interest rates and thus If a firm liquidates a LIFO layer in the first three quarters of the year that it expects to replace by year-end, the liquidation quarter’s cost of goods sold is charged for the expected cost of replacement. The offsetting credit is assigned to a temporary (liability) account since inventory is not reduced. A handful of natural gas firms disclosed “temporary” LIFO liquidations during our sample period but these events are not included in the final sample. 5 6 Dopuch and Pincus (1988) summarize early research on the economic incentives associated with LIFO/FIFO choice and Fields, Lys and Vincent (2001) a review recent empirical accounting choice research. 4 high inventory carrying costs (Schiff 1983).7 Reductions in firm size or scope (e.g., plant closures or shuttering of retail outlets), supply disruptions (e.g., labor strike at a vendor or transportation company), unanticipated customer demand, or the adoption of new processes and technologies that reduce optimal inventory levels (e.g., just-in-time manufacturing) may contribute to LIFO liquidations. Little attention has been devoted to these factors although LIFO liquidation firms do tend to exhibit negative pre-liquidation changes in annual earnings (Davis et al. 1984; Tse 1990), a result that may reflect a slackening in product demand. Dhaliwal et al. (1994) develop a multivariate model of the LIFO liquidation decision and find that tax minimization, earnings management, and debt covenants all provide inventory liquidation incentives. Two earnings management variables are considered: the change in annual earnings (before extraordinary items) and the variability of annual earnings. Sweeney (1994) finds that LIFO liquidations are prevalent among firms close to debt covenant violation. Hunt et al. (1996) find that LIFO firms manage inventory levels to smooth reported earnings and lower debtrelated costs but not to minimize taxes. Managers of LIFO firms apparently forego incremental tax savings—which could be gained by better managing inventory quantities—in order to smooth reported earnings and to lower current and future covenant-related costs.8 In summary, there is scant evidence on whether earnings threshold considerations influence LIFO liquidation decisions, and mixed evidence on the importance of tax cost considerations. The extant evidence on the determinants of LIFO liquidation decisions is based on small samples of Until the early 1980s, the only significant occurrence of LIFO liquidation involved firms in the steel industry during the Korean War period (Schiff 1983). At that time, the demand for steel was strong, prices were high and a steelworker’s strike contributed to decreasing inventory levels. Congress was petitioned to modify the tax law to permit the liquidation of low-cost LIFO inventory without the tax on high profits that would result from involuntary liquidation. Congress refused and steel inventories weren’t liquidated despite strong market demand. 7 8 Fields et al. (2001) note that the simultaneous equations approach to studying managers’ adjustments to interacting accounting measures (inventory management, depreciation, and other current accruals) used by Hunt et al. 1996) has not achieved general acceptance by other researchers, possibly because it requires explicit assumptions about the costs and effectiveness of various accounting choices—assumptions which are made only implicitly in much of the accounting choice research. 5 annual LIFO liquidations occurring before 1990. Our study relies on a large and timely sample of quarterly liquidations to provide direct evidence on the importance of earnings benchmark and tax cost incentives. 2.2 Investor reaction to LIFO liquidations Most firms announce quarterly and annual earnings in summary form (via a press release) several days prior to public distribution of complete financial statements. Press releases are prepared for limited distribution to the financial press and are the basis for the publication of “earnings announcements” in print and electronic media (e.g., The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg and PR Newswire). Complete financial statements are first released to the public at a later date, typically as part of quarterly (10-Q) or annual (10-K) reports filed with the SEC. The SEC requires firms to disclose “material” LIFO liquidation holding gains in financial statements.9 This disclosure is presumably intended to help investors properly gauge the quality of reported earnings since LIFO liquidation gains are transitory “paper profits” and not indicative of a firm’s ability to generate future cash flows. Disclosure is not required in earnings press releases, which are largely unregulated and not audited.10 Stober (1986) examines the share price response to LIFO liquidations for a sample of 559 events by 272 firms during 1979-1983. A positive share price response to LIFO liquidation gains 9 Whenever a company “includes a material amount of income in its income statement which would not have been recorded had the inventory liquidation not taken place,” SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin 40, Topic 11F (1981) requires disclosure of this income component either in a footnote or parenthetically on the face of the income statement. SAB No. 40 codifies earlier Bulletins. As Stober (1986) notes, even though footnote disclosure of supplemental information can be omitted from 10-Q filings, disclosures of LIFO liquidations would appear to fall under the category of “disclosures necessary for fair presentation” that (under SEC Accounting Series Release No. 286) must be provided with financial statements in 10-Q reports. 10 In March 2003, the SEC issued strict and comprehensive rules governing the use of non-GAAP financial measures in press releases and SEC filings (SEC 2003). A byproduct of these new rules is the requirement (Item 12) to furnish a Form 8-K within five business days of any public announcement or release disclosing the registrant’s results of operations or financial condition for an annual or quarterly period that has ended. Earnings announcement press releases are now routinely available in their original (“as released”) form because the registrant is required to include the announcement or release as an exhibit to the 8-K filing. 6 is predicted at the earnings announcement date because they are presumed to be both unexpected and undisclosed in the earnings press release. The (undisclosed) LIFO liquidation gain is thus predicted to be priced in tandem with regular earnings. A negative market reaction (or “reversal”) is predicted at the financial statement release date when the LIFO gain is first made public. Reversal is predicted because LIFO liquidation gains are “paper profits.” Contrary to these predictions, the mean share price reaction at each announcement date is statistically indistinguishable from zero. Stober (1986) does find weak evidence of a positive share price response to LIFO holding gains for the ten-day period around the financial statement release date. Tse (1990) controls for analysts’ earnings expectations and firms’ tax status (i.e., tax loss carry-forward availability) when testing for a share price response to (undisclosed) gains from liquidating LIFO inventory. The sample is comprised of 396 annual LIFO liquidations during 1980-1984. Stock returns are measured over a five-trading day window centered on the annual earnings announcement date. No sample-wide share price reaction to LIFO liquidation gains is detected. However, firms with low tax rates experience a positive market reaction to LIFO gains.11 In summary, there is little evidence to suggest that LIFO liquidation holding gains are priced at the earnings announcement date or later at the financial statement release date. However, neither prior study tests for share prices responses to LIFO liquidation gains conditioned by benchmark beating. Our research addresses this issue using an expanded and timelier sample. 2.3 Research Questions Fields, Lys and Vincent (2001) review several prior studies on the stock market reaction to LIFO adoption. They point to mixed and inconsistent evidence of that stock returns at LIFO adoption reflect the income tax benefits of LIFO. 11 7 Prior research shows firms “manage” reported earnings to produce positive profits, to avoid earnings decreases, and to meet or exceed analysts’ earnings expectations (Hayn 1995, Burgstahler and Dichev 1997, Degeorge et al. 1999, Burgstahler and Eames 2002). The most salient of these earnings benchmarks seems to be analysts’ EPS forecasts (Brown and Caylor 2004). Managers say that they are motivated to beat analysts’ quarterly EPS forecasts to build credibility and preserve their reputation with capital markets, to maintain or increase the firm’s stock price, and to avoid the uncertainty created by missing the forecast (Graham, Harvey and Rajgopal 2005). These concerns appear well founded. There is a valuation premium associated with meeting or beating analysts’ forecasts (Bartov et al. 2002; Kasznik and McNichols 2002) and missing the forecast by even a penny can lead to a dramatic loss in firm value (Skinner and Sloan 2002). Our tests for earnings management also use analysts’ consensus quarterly EPS forecasts as the relevant earnings benchmark.12 If managers use LIFO liquidations to meet or beat analysts’ quarterly EPS targets then we should observe an abnormally large concentration of accretive liquidations among firms that, absent the LIFO layer dip, would have fallen short of the EPS target that quarter. Thus, we test the following hypothesis (stated in alternative form): H1: The level of accretive LIFO liquidations is disproportionately high for firms with small negative pre-liquidation quarterly EPS forecast errors. Evidence bearing on this hypothesis is developed from both univariate tests of LIFO liquidation frequency (Hribar, Jenkins, and Johnson 2006) and from multivariate tests that control for known determinants of LIFO liquidation decisions. Our next set of hypotheses ask whether investors recognize and price the LIFO liquidation component of the quarterly earnings surprise. LIFO liquidations are typically not disclosed until financial statements (10-Q or 10-K) are filed with the SEC several days after quarterly earnings 12 We intend to augment these tests using EPS from the same quarter last year as the earnings benchmark. 8 are announced. Only about 7.9% of LIFO liquidation in our sample are disclosed in the earnings press release. Investors who learn of (or anticipate) the liquidation can decompose the quarterly earnings surprise into one component attributable to the liquidation and another component that reflects operating performance. Prior research has shown that investors discount earnings surprise components that are likely to be managed (Defond and Park 2001). If investors discern and price the liquidation’s EPS impact, earnings announcement stock returns will reflect the combined implications of both the operating performance component and the liquidation component of the earnings surprise. The earnings response coefficients assigned by investors to each component should differ from one another because the two components convey different information about future firm performance. Moreover, liquidations intended to boost EPS should convey less value relevant information than those intended to signal optimism or undertaken for reasons unrelated to EPS management. Thus, we expect the liquidation response coefficient to be diminished among firms that would have fallen short of analysts’ EPS targets without the liquidation. This leads to our second set of hypotheses (in alternative form): H2a: Investors separately price the liquidation-induced component of quarterly EPS surprises. H2b: Investors assign a lower price to the liquidation-induced component of quarterly EPS surprises when the liquidation is used to meet or beat analyst forecasts. Evidence indicating that investors recognize and discount the liquidation-induced component of quarterly earnings surprises would raise questions about the effectiveness of LIFO liquidations as an earnings management device. Some managers may believe (perhaps falsely) that investors are functionally fixated on reported EPS and will fail to detect the liquidation and its earnings surprise impact. The possibility that some liquidations go undetected seems plausible given the limited disclosure of liquidations in earnings press releases. Alternatively, managers may believe that, although investors are likely to spot the liquidation and discount its earnings 9 surprise impact, the discount is smaller than the “earnings torpedo” penalty that would be incurred in the absence of the liquidation (Skinner and Sloan 2002). 3. Sample Selection 3.1 Sample Selection LIFO liquidations disclosed between January 1, 1994 and April 30, 2008 are identified from text string searches of Securities and Exchange Commission’s electronic documents.13 We adapt text strings in Stober (1986) and Dhaliwal et al. (1994) and search quarterly and annual financial reports (10-Qs and 10-Ks) and earnings press releases (8-K). 14 Liquidations that decrease quarterly earnings, occur in a prior quarter, or are reported as part of discontinued operations are discarded from the sample. This process identifies a preliminary sample of 1,679 confirmed quarterly liquidations disclosed in financial statements. Of these, only 132 (7.9%) are also disclosed in earnings press releases.15 Non-liquidation LIFO firms are from Compustat and are required to have a positive beginning-of-year LIFO reserve of at least 2 cents per share, on an after-tax basis, for a given year in the liquidation sample period. The non-liquidation sample is thus limited to firm/years 13 The Securities and Exchange Commission’s EDGAR database contains very few documents filed before 1994. Stober (1986) searched annual financial statements included in the National Automated Accounting Research System (NAARS) database and earnings announcements appearing on the Broad Tape, accessed through the Dow Jones News Retrieval Service, using the phrase: LIQUIDAT! OR (QUANTIT! W/15 DECREAS! OR REDUCT!) W/20 LIFO. Dhailwal et al. (1994) use this same test string to search the annual financial statements in the NAARS database. We use the Morningstar Document Research (formerly 10-K Wizard) system to search SEC filings, and implement Stober’s (1986) Boolean expression iteratively to accommodate the limitations of that system. We also augment the text search string to accommodate variations in the LIFO text reference (e.g., “last in, first out”) and in the way firms’ describe their inventory quantity reductions (e.g., “draw-downs” or “decrements”). The search process identified 3,085 10-K or 10-Q filings, and 632 8-K filings, that were then read to confirm the quarterly liquidation and handcollect the requisite data. 15 Until 2003, firms were not required to include the text of their quarterly earnings press release in 8-K filings. Consequently, we augmented our search for LIFO liquidation disclosures in earnings press releases using the electronic document capabilities of Factiva. The search was limited to company press releases provided to Factiva by Dow Jones News Service, PR Newswire, and Business Wire. These documents are sometimes edited by the news services and thus may not contain the exact press release text as issued by the firm. 14 10 where modest LIFO inventory quantity reductions can increase reported quarterly earnings per share by ½ cent or more. We discard regulated utilities (SIC codes 4900-4999). The liquidation of LIFO fuel inventories in this industry segment does not affect reported earnings since the effect must be passed through to customers as part of regulated tariffs. We also discard finance, insurance, and real estate firms (SIC codes 6000-67999) because LIFO inventories are unrelated to the core business activities of these firms. This process yields a preliminary sample of 8,264 LIFO firm/years representing 1,110 unique firms. We discard firm/quarter observations where the quarterly earnings announcement date falls outside the liquidation disclosure period or where earnings announcement stock returns (day -5 to +5) are not available from the CRSP daily returns file. These same filters are also applied to preliminary LIFO liquidation sample. The selection process yields a LIFO liquidation sample comprised of 1,204 firm/quarters involving 317 unique firms and a pooled (liquidation and non-liquidation) LIFO population of 27,423 firm/quarters and 1,016 unique firms. 3.2 Descriptive Statistics Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the LIFO liquidation and non-liquidation samples. Panel A shows the frequency of sample observations by year and fiscal quarter. LIFO liquidations are clustered in the fourth fiscal quarter (84.1% of the sample) but exhibit little clustering by year. Panel B describes firms’ unrecognized LIFO holding gains (i.e., the LIFO balance sheet reserve), recognized liquidation gains, and characteristics of the LIFO liquidation disclosures. The median after-statutory-tax LIFO reserve is $0.740 per share, indicating that firms have substantial ability to “manage” quarterly EPS by drawing down LIFO inventory quantities. The median after-tax LIFO liquidation gain is $0.053 per share for events where a dollar amount is disclosed. The LIFO liquidation gain is deemed as “not material” in 16.6% of the sample events and no dollar amount is disclosed by management. 11 Most LIFO liquidations are disclosed contemporaneously in firms’ 10-Q or 10-K filings but 11.0% of the sample events are not disclosed until a subsequent quarter. These “stealth” liquidations often involve recognized holding gains deemed “not material” at the time. They surface later in firms’ 10-Q or 10-K filings that disclose a larger contemporaneous LIFO liquidation and are described as prior period events. Roughly half of the liquidation events are preceded by a liquidation in the prior four quarters, and 42.9% of the LIFO liquidation holding gains are disclosed as after-tax amounts. Very few LIFO liquidations are disclosed in firms’ quarterly earnings press releases.16 3.3 LIFO Firms and Earnings Thresholds Do LIFO firms exhibit the familiar discontinuity around zero in the distribution of quarterly earnings surprises documented by Burgstahler and Dichev (1999) and Degeorge et al. (1999) in samples containing both LIFO and non-LIFO firms? To confirm the kink for our restricted LIFO sample, we construct a quarterly earnings surprise metric defined as the I/B/E/S “actual” EPS minus the final I/B/E/S consensus (median) EPS forecast. Requiring I/B/E/S earnings forecasts reduces our pooled LIFO sample to 21,621 (78.8% of the original sample). Firm-quarter observations are sorted into bins based on the magnitude of the quarterly earnings surprise and without removing the EPS impact of any LIFO liquidation holding gains. Figure 1 depicts the frequency distribution of quarterly earnings surprises among LIFO firms using forty-one bins that range from -20 cents to +20 cents per share. Earnings surprises greater than 20 cents per share in absolute value (1,712 firm-quarter observations, or 7.9%).are discarded for brevity. LIFO firms do indeed exhibit a discontinuity around zero in the distribution of I/B/E/S quarterly earnings surprises. A disproportionately small number of earnings surprise observations fall to the left of zero in Figure 1. For example, roughly 28% of the pooled LIFO sample just 16 Because firms were not required to include quarterly earnings press releases in 8-K filings for the entire sample period, we augmented our investigating by searching press releases contained in the Dow Jones’ Factiva database as described in footnote 14. A collateral benefit of this research step is that uncovered several instances where LIFO liquidations described in 8-K press releases were not mentioned in the edited Factiva press release. 12 “meets or beats” the earnings benchmark (0 and +1 cent bin) whereas only 7.0% of the sample just “misses” the benchmark (-1 cent bin). Untabulated results reveal no discernable difference between Figure 1, which reflects earnings surprises in all fiscal quarters, and the distribution of fourth quarter earnings surprises. Roughly 14.8% (11.7%) of the fourth quarter earnings surprises fall into bin zero (+1 cent) whereas only 7.0% fall into the -1 cent bin. The next section provides evidence on the extent to which LIFO liquidation holding gains contribute to the observed discontinuity in the distribution of LIFO firms’ quarterly earnings surprises. 4. Evidence on Benchmark Beating 4.1 Methods Firm-quarter observations for liquidation and non-liquidation LIFO firms are sorted into bins based on the magnitude of the ex-ante (pre-liquidation) quarterly earnings surprise. We continue to use the I/B/E/S consensus EPS forecasts and I/B/E/S “actual” EPS data to measure the earnings surprise. The ex-ante earnings surprise for non-liquidation LIFO firms is actual EPS minus the beginning-of-quarter consensus EPS forecast, as opposed to the end-of-quarter forecast used in Figure 1. Beginning-of-quarter EPS forecasts are used to ensure that earnings thresholds are known by managers before quarterly liquidation decisions are made (Roychowdhury 2006). For liquidation firms, we also subtract the after-statutory-tax EPS impact of the liquidation. We then compute the relative frequency of liquidations of at least 0.5 cents per share and less than 10 cents per share in each earnings surprise bin. We focus on liquidations large enough to move EPS by one cent and we exclude large liquidations that are too large to be motivated by earnings management. If liquidations are used to manage reported quarterly EPS, they will be 13 disproportionately more (less) frequent among firms with small negative (positive) pre-liquidation earnings surprises. The pattern in Figure 2 is consistent with our expectations. Liquidations are concentrated among firms that faced negative ex-ante earnings surprises absent the LIFO liquidation, consistent with poor performance or earnings management incentives. The effects of poor performance are evident in the relatively high number of liquidations among firms with ex-ante negative earnings surprises of more than ten cents. The distinct difference in the number of liquidations for firms close to zero earnings surprise is consistent with earnings management incentives. Firms that just beat the ex-ante forecast are significantly less likely to liquidation inventory than are firms that just miss the forecast. This univariate test of earnings management is complemented by multivariate tests that control for factors that may affect LIFO liquidation decisions. 17 To isolate the influence of earnings thresholds on LIFO liquidation decisions, we estimate a probit regression of a binary variable (LIQUID = 1 or 0) on variables conjectured to predict the occurrence of accretive liquidations. The estimation equation has the following form: ∑ where (1) is the logged odds of a LIFO liquidation occurrence, MISS is an indicator variable denoting firms with negative pre-liquidation quarterly earnings surprises, and is the vector of coefficient estimates and control variables. Subscripts denoting firm and quarter are suppressed for brevity. The estimation sample includes both liquidation and non-liquidation LIFO firms. If liquidations are used by some firms to manage reported quarterly EPS, they will be 17 These factors constitute plausible correlated omitted variables in the univariate test. 14 disproportionately more likely to occur among MISS firms than among firms that beat the forecast (captured by the intercept), meaning that is predicted to be positive. Control variables capture information about factors other than earnings thresholds that might also influence LIFO liquidation decisions: firms’ tax status, changes in operations, debt covenant incentives. Two tax status variables are included: the firm’s effective tax RATE and beginning-of-year availability of net operating loss carry-forwards (NOL). Variables that proxy for operational changes include: the percentage change in year-over-year sales for the quarter (∆SALES); and indicator variables denoting a quarterly LOSS or earnings disappointment (BADNEWS). Our proxy for debt covenant incentives is financial leverage (LEV). Three other explanatory variables are included in the model: beginning-of-year after-tax LIFO reserve per share (LRES), which proxies for liquidation opportunities; and LAGLIQ, which denotes one or more LIFO liquidations by the firm in the previous four quarters. Year fixed-effects are included.18 All variables are defined more completely in the appendix. Table 2 reports descriptive statistics on these variables for non-liquidation and liquidation firm/quarters. For multivariate test purposes, we limit the sample to firm/quarters where the earnings surprise falls between -10 and +9 cents per share. This restriction focuses the test on firms where LIFO liquidations are likely to have an impact on firms’ ability to meet EPS targets. Consistent with statutory tax rates during our sample period, the mean ETR for both groups of firms is approximately 35 percent. Consistent with our expectations, liquidation firms are more likely to have NOLs than are non-liquidation firms (28% versus 22%, respectively). As a result, liquidation firms likely face lower liquidation tax costs. On average, non-liquidation firms experience higher sales growth during the current quarter and the subsequent quarter than do liquidation firms. Approximately six percent of liquidation firms experience an operating loss in Results are robust to including indicator variables for industries defined by two-digit SIC codes. We have an insufficient number of observations to use finer industry groupings. 18 15 the current period, which is significantly more than the three percent of non-liquidation operating loss firms. Liquidation firms also have greater opportunity to liquidate LIFO inventory at a gain, as measured by the beginning of period reserve. Liquidation firms have approximately 87 cents per share of potential liquidation gains as opposed to only 51 cents per share for non-liquidation firms. Most LIFO liquidations occur in firms that had a LIFO liquidation in one of the preceding four quarters (LAGLIQ = 0.68). More than 80 percent of all liquidations occur in the fourth quarter of the fiscal year. Because of this fiscal quarter concentration, we examine fourth quarter liquidations separately in the subsequent analysis. Panel B of Table 2 reports bivariate correlation coefficients for the variables used in the regression. Consistent with H1, the occurrence of a quarterly LIFO liquidation (LIQUID) is significantly positive correlated with whether the firm misses ex-ante the EPS forecast (MISS). Liquidation is also more likely for NOL firms, consistent with a lower tax-cost for these firms. As in prior research, we do not find a significant association between firms’ effective tax rates and the incidence of LIFO liquidation. Liquidation is more likely for firms with sales declines in the current and subsequent period and for firms with operating losses, consistent with the notion that poor operating performance leads some firms to reduce inventory levels. The incidence of liquidation is decreasing in leverage but increasing in the magnitude of the LIFO reserve. We are cautious about drawing inferences from these univariate correlations, however, because they fail to control for the correlation among predicted determinate factors. We note that many of the explanatory variables exhibit significant correlation with other factors, although the correlations are relatively small in magnitude (the largest between LAGLIQ and LRES is less than 17%) and thus we do not expect multicolinearity to be a problem. 4.2 Results 16 To investigate H1, we estimate model 1 for the sub-sample of firms within -10 to +9 cents of the analysts’ consensus forecast (ex-ante) and for a narrower earnings surprise band of -4 to +3 cents per share. We estimate the regression for all four quarters and for the fourth quarter separately. The results are reported in Table 3. These results confirm that the frequency of LIFO liquidations is higher among firms that just miss analysts’ EPS benchmarks. Firms that miss the exante forecast are more likely to liquidate LIFO inventory quantities than are firms that beat the forecast. In addition, the LIFO reserve levels and past liquidations are significantly, positively associated with the likelihood of a LIFO liquidation. Consistent with the univariate results, we find that opportunity to liquidate inventory as well as past liquidations have significant explanatory power for current liquidations. We find no support for tax costs affecting the decision to liquidation inventory in this sample. The current period change in sales is negatively associated with liquidations in the fourth quarter and in the full sample for the small range of firms with absolute ex-ante forecast errors less than four cents. Overall, Figure 2 and Tables 2 and 3 provide support for the conclusion that some firms liquidate inventory accounted for under LIFO in order to meet analysts’ EPS forecasts. Benchmark beating incentives have incremental explanatory power as a determinant of LIFO liquidation decision relative to tax costs and current and future firm performance considered in prior research. Benchmark beating incentives also have incremental explanatory power relative to LIFO reserve levels (i.e., the opportunity to manage earnings using LIFO) and past liquidation decisions. These management incentives appear to be successful, as the distribution in Figure 1 exhibits the classic discontinuity just below the zero earnings surprise bin. 5. Evidence on Investor Reaction 5.1 Methods: Quarterly Earnings Announcement Returns 17 This section describes the methods used to determine if investors separately price the (undisclosed) LIFO liquidation-induced accretive component of firms’ quarterly earnings surprise (H2a) or assign different prices to firms that seemingly use liquidations to meet or beat analysts’ EPS forecasts (H2b). Because we are interested in isolating investors’ response to information released at the earnings announcement date, we limit our attention to stock returns cumulated over day -1 through day +1, where day 0 corresponds to the quarterly earnings announcement date. Consistent with this focus on narrow window stock returns, we redefine the earnings surprise measure (denoted UE) as the difference between I/B/E/S “actual” quarterly EPS and the last consensus EPS forecast from I/B/E/S. The earnings surprise for liquidation firms is then decomposed into one component that reflects operating performance (UE_OP) and a second component that reflects the estimated impact of the liquidation holding gain (UE_Liquid). The sample is comprised of liquidation and non-liquidation LIFO firm/quarters. Our approach (Model 1) presumes that firms’ LIFO liquidation holding gains each quarter are unexpected by investors. UE_GAIN is thus set equal to the after-statutory-tax EPS impact of liquidation; i.e., the after-tax liquidation holding gain. This approach understates investors’ liquidation expectations if LIFO liquidations are predictable events.19 To examine how investors price the (undisclosed) LIFO liquidation component of firms’ quarterly earnings surprises, we estimate an expanded version of the traditional earnings/returns model (Hribar, Jenkins, Johnson 2006): CAR3 = α0 + α1Liquidation + α2UE_GAIN/P +α3UE /P + α4 UE /P*LOSS + α5 UE/P*Siz+ α6 UE /P *Beta + α7UE/P*Growth + ε (2) where CAR3 is the three-day cumulative size-adjusted abnormal stock return surrounding the earnings announcement date, UE is total unexpected earnings defined as “actual” EPS from 19 We will address this issue in the next version of the manuscript. 18 I/B/E/S minus the most recent IBES consensus forecast, UE_GAIN is the earnings surprise attributable to a LIFO liquidation holding gain during the quarter (as defined by Model 1 or Model 2), and P is the closing share price for the previous quarter. By including both UE_GAIN and UE in the regression, the response coefficient on the LIFO liquidation holding gain component of the earnings surprise is given by α2 + α3. A significant negative coefficient for α2 indicates that the earnings surprise attributable to accretive LIFO liquidations is priced lower than the earnings surprise resulting from operating activities. If the α2 coefficient estimate is zero, then investors do not differentially price the liquidation holding gain. 20 The indicator variable Liquidation equals one if the firm experienced a LIFO liquidation during the quarter, and zero otherwise. The Liquidation coefficient estimate will be positive if investors respond favorably to the revelation that a firm had a gain as the result of a LIFO liquidation during the quarter. The regression specification includes control variables that are known to affect the earnings/returns relation. Following Hayn (1995), we include LOSS as an indicator variable that equals 1 when reported EPS (as defined by I/B/E/S) is negative and zero otherwise. We also include proxies for risk and growth (Collins and Kothari 1989). Beta proxies for risk and is the decile rank of market-model beta estimated using rolling 60-month regressions. Following DeFond and Park (2001), Growth is an indicator variable that equals 1 when the percentage change in book value of equity for the previous year is above the sample median, and zero otherwise. The indicator variable Size equals 1 when the firm is above the median market capitalization for our sample. The coefficient estimates for LOSS and Beta are predicted to be negative whereas positive coefficient estimates are predicted for Growth and Size. All non- indicator variables are deflated by the beginning-of-quarter share price. We estimate the 20 The UE_GAIN regression coefficient estimate may be biased towards zero if investors anticipate liquidations. 19 regression equation using all firm-quarters. To control for heteroscedasticity and cross-correlation in the data, we use robust standard errors and cluster by quarter (Wooldridge 2002). 4.2 Test Results: Quarterly Earnings Announcement Returns Panel A of Table 4 reports market-adjusted stock returns for the 10 days surrounding the quarterly earnings announcement date (Day 0) and the results of estimating the cross-section regression Model 2. Non-liquidation firms experience statistically positive abnormal returns in the three-day earnings announcement window (Day -1 to +1) but the returns for liquidation firms are not reliably different from zero. Panel B of Table 4 reports the estimated coefficients for three-day announcement window return regression (Model 2). For estimation purposes, the sample excludes liquidations that are designated by management as “not material” as well as those where the disclosed per share impact is less than $0.005 or greater than $0.10. The results are similar using all firm/quarters or just fourth quarter observations. The total earnings surprise (UE) response coefficient is reliably positive. The incremental response coefficients associated with the control variables are generally significant and directionally consistent with prior research. Large firms have a significantly larger UE response coefficient than smaller firms and loss firms have a significantly smaller response coefficient than do profitable firms. Beta and Growth are also directionally consistent with our expectations and sometimes significant. The coefficient estimate associated with our primary variable of interest (UE_GAIN) is negative and significant in both estimation samples (one-tailed p-values of 0.0029 and 0.0373 respectively). This is consistent with investors discounting the EPS earnings surprise component arising from an accretive LIFO liquidation. Despite the negative incremental coefficient associated with UE_GAIN, investors do not assign a negative price to the liquidation-induced earnings surprise because the combined coefficient (α2+α3) is not statistically different from zero in either 20 sample (p-value 0.3758 and 0.9434, respectively). Overall, the investors appear to discount the LIFO liquidation gain portion of the earnings surprise. 4.3 Test Results: Market Response to Liquidations to Beat Benchmarks To test hypothesis 2b, we modify model 2 to include an indicator variable for whether the firm missed the beginning-of-quarter consensus EPS forecast after subtracting the after-tax per share LIFO liquidation holding gain. We expect investors to respond more negatively to the LIFO holding gain component of the earnings surprise when the liquidation seems to have been motivated by earnings management incentives. Table 5 reports the results of estimating this modified regression. The UE_GAIN and MISS interaction coefficient is of primary interest. Surprisingly, this incremental response coefficient is reliably positive in both estimation samples (p-value =0.0001 for Q1-Q4 and 0.0573 for Q4), indicating that investors apparently “reward” firms that use LIFO liquidations to achieve their EPS targets.21 One explanation for this result is that investors discount less LIFO liquidations motivated by earnings management incentives because the recognized holding gains have less negative implications for future sales and profitability. 6. Conclusions We examine whether firms liquidate inventory quantities accounted for using the LIFO method to beat quarterly earnings benchmarks. Our sample includes more than 1,000 quarters where firms liquidated LIFO inventories. We require liquidation and non-liquidation sample firms to have LIFO reserves of at least two cents per share as of the beginning of the year. Thus, our sample is comprised of firms that can increase EPS by a half cent per share with just a modest Inferences are similar if we condition instead on whether firms’ meet or beat the EPS target implied by the final consensus forecast prior to the quarterly earnings announcement. 21 21 reduction in inventory levels. To examine the association between benchmark beating and liquidations, we exclude liquidations smaller than one-half cent per share and larger than ten cents per share, a range that focuses our tests on liquidations plausibly motivated by earnings management incentives. We find a significant increase in the likelihood of a liquidation when firms would miss the beginning-of-quarter consensus forecast before considering the effect of the liquidation. This effect is concentrated in the fourth quarter of the fiscal year. The association between liquidations and benchmark incentives is incremental to tax and profitability considerations that undoubtedly also influence managers’ inventory liquidation decisions. We examine the market response to earnings announcements. Although prior research has generally been unable to detect a LIFO-liquidation market response to earnings announcements, we document a reliably negative incremental response to the liquidation holding gain component of unexpected earnings. However, when this negative incremental coefficient is combined with the positive earnings surprise coefficient, the overall impression is that investors simply spot and then ignore LIFO liquidation holding gains because the combined coefficient is not different from zero. Surprisingly, the incremental reaction to LIFO liquidation holding gains is reliably positive for firms where the liquidation appears motivated primarily by benchmark beating incentives. We conjecture that investors may heavily discount other liquidations because they are associated with sales and profitability declines and thus have greater persistence. 22 References APB Opinion No. 28, Interim Financial Reporting, Accounting Principles Board May 1973. New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. Bartov E., D. Givoly and C. Hayn. 2002. The rewards to meeting or beating earnings expectations. Journal of Accounting & Economics 33: 173-204. Biddle, G. 1980a. Accounting methods and management decisions: The case of inventory costing and inventory policy. Journal of Accounting Research (Supplement): 235-280. Biddle, G. 1980b. A reply. Journal of Accounting Research (Supplement): 292-295. Brown, L. and M. Caylor. 2004. A temporal analysis of earnings management thresholds. Working paper, Georgia State University. Burgstahler, D. and I. Dichev. 1999. Earnings management to avoid earnings decreases and losses. Journal of Accounting and Economics 24: 99-126. Burgstahler, D. and M. Eames. 2002. Management of earnings and analysts’ forecasts to achieve zero and small positive earnings surprises. Working paper, University of Washington. Davis, H., N. Kahn and E. Rozen. 1984. LIFO inventory liquidations: An empirical study. Journal of Accounting Research 22: 480-496. DeFond, M. and C. Park. 2001. The reversal of abnormal accruals and the market valuation of earnings surprises. The Accounting Review 76: 375-404. Degeorge, F., J. Patel and R. Zeckhauser. 1999. Earnings management to exceed thresholds. Journal of Business 72: 1-33. Dhaliwal, D., M. Frankel and R. Trezevant. 1994. The taxable and book income motivations for a LIFO layer liquidation. Journal of Accounting Research 32: 278-289. Dhaliwal, D., C. Gleason, and L. Mills. 2004. Last-chance earnings management: Using the tax expense to meet analysts’ forecasts. Contemporary Accounting Research 21: 431-59. Dopuch, N. and M. Pincus. 1988. Evidence on the choice of inventory accounting methods: LIFO versus FIFO. Journal of Accounting Research 26: 28-59. Fields, T., T. Lys and L. Vincent. 2001. Empirical research on accounting choice. Journal of Accounting and Economics 31: 255-307. Frankel, M. and R. Trezevant. 1994. The year-end LIFO inventory purchasing decision: An empirical test. The Accounting Review 69: 382-398. Graham, J. R., C. R. Harvey and S. Rajgopal. 2005 The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics. Grullon, G. and R. Michaely, 2004 The information content of share repurchase programs, Journal of Finance 59 (2004), pp. 651–680. Hayn, C. 1995. The information content of losses. Journal of Accounting and Economics 20: 125-153. 23 Hribar, P., N. Jenkins and W. Johnson. 2006. Stock repurchases as an earnings management device. Journal of Accounting and Economics 41 : 3-27. Hunt, A. S. Moyer, and T. Shevlin. 1996. Managing interacting accounting measures to meet multiple objectives: A study of LIFO firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics 21: 339-374. Ikenberry, David, Josef Lakonishok, and Theo Vermaelen, “Market Underreaction to Open Market Share Repurchases,” Journal of Financial Economics (1995): 181–208. Jennings, R., P. Simko and R. Thompson. 1996. Does LIFO inventory accounting improve the income statement at the expense of the balance sheet? Journal of Accounting Research 34: 85-109. Kasznik, R. and M. F. McNichols. 2002. Does meeting earnings expectations matter? Evidence from analyst forecast revisions and share prices” Journal of Accounting Research 40: 727-759. McNichols, M., Wilson, G.P.1988. Evidence of earnings management from the provision for bad debts. Journal of Accounting Research 26: 1-31. Moehrle, S. 2002. Do firms use restructuring charge reversals to meet earnings targets? The Accounting Review 77: 397-413. Morse, D. & Richardson, G. (1983). The LIFO/FIFO decision. Journal of Accounting Research 21: 106-127. Pincus, M. 1986. Discussion of the incremental information content of financial statement disclosures: The case of LIFO inventory liquidations. Journal of Accounting Research 24: 161-164. Roychowdhury, S. 2006. Earnings management through real activities manipulation. Journal of Accounting and Economics 42: 335-370. Schiff, A. 1983. The other side of LIFO. Journal of Accountancy May: 120-121. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2003. Conditions for Use of Non-GAAP Financial Measures. Release No. 33-8176, March 28. Skinner, D. J. and R. G. Sloan. 2002. Earnings surprises, growth expectations and stock returns, or, don’t let an earnings torpedo sink your portfolio. Review of Accounting Studies 7: 289-311. Stober, T. 1986. The incremental information content of financial statement disclosures: The case of LIFO inventory liquidations. Journal of Accounting Research 24: 138-160. Sweeney, A. 1994. Debt-covenant violations and managers’ accounting responses. Journal of Accounting and Economics 17: 281-308. Tse, S. 1990. LIFO liquidations. Journal of Accounting Research 28: 229-238. 24 Appendix: Variable Definition and Measurement Earnings Threshold: MISS denotes a negative pre-liquidation quarterly earnings surprise, measured as I/B/E/S “actual” EPS minus the I/B/E/S consensus (mean) EPS forecast. The after-tax per share LIFO liquidation holding gain is subtracted from the I/B/E/S “actual” EPS for liquidation firm/quarter observations. Tax Status: RATE the firm’s effective tax rate, measured as prior quarter tax expense divided by pre-tax earnings for that same quarter. Contemporaneous tax expense and pre-tax earnings are used for the first fiscal quarter. NOL denotes the beginning-of-year availability of net operating loss carry-forwards. Changes in Operations: ∆SALES percentage change in year-over-year quarterly sales for the current quarter. ∆SALES+1 percentage change in year-over-year quarterly sales for the next (forward) quarter. LOSS denotes a reported net operating loss for the quarter. Debt Covenant Incentives: LEV financial leverage, measured as the beginning-of-quarter ratio of long-term debt (including current maturities) divided by total assets (adjusted for the LIFO reserve). Other: LRES beginning-of-year after-tax LIFO reserve per share. LAGLIQ denotes the occurrence one or more LIFO liquidations by the firm in the prior four quarters. Q4 denotes the fiscal fourth quarter. 25 Figure 1. The Distribution of LIFO Firms’ Quarterly Earnings Surprises This chart depicts the relative frequency quarterly earnings surprise among LIFO firms in our sample. The earnings surprise metric is constructed from final I/B/E/S consensus EPS forecasts and I/B/E/S “actual” EPS data. Firm-quarter observations are sorted into bins based on the magnitude of the quarterly earnings surprise without removing the EPS impact of any LIFO liquidation holding gains. Forty-one earnings surprise bins that range from -20 cents to +20 cents per share are used. There are 19,909 firm/quarter earnings surprise observations depicted in the chart. Earnings surprises greater than 20 cents per share in absolute value are not depicted (1,712 observations). 16 14 12 Percent 10 8 6 4 2 0 -0.20 -0.18 -0.16 -0.14 -0.12 -0.10 -0.08 -0.06 -0.04 -0.02 0 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0.10 0.12 0.14 0.16 0.18 0.20 Quarterly earnings surprises (AFE) 26 Figure 2. The Relative Frequency of LIFO Liquidations This chart depicts the relative frequency of quarterly LIFO liquidations in each of forty-one ex-ante (pre-liquidation) earnings surprise bins that range from -20 cents to +20 cents per share. The earnings surprise metric is constructed from beginning-of-quarter I/B/E/S consensus EPS forecasts and I/B/E/S “actual” EPS data. The ex-ante earnings surprise for non-liquidation LIFO firms is the actual EPS minus the beginning-of-quarter consensus EPS forecast. For liquidation firms, the after-statutory-tax EPS impact of the liquidation is also subtracted. Each column bar denotes the relative frequency of LIFO liquidations occurring in a given quarterly earnings surprise bin. LIFO liquidations that contribute less than ½ cent per share or more than 10 cents per share are not depicted (127 observations). 0.08 0.07 Frequency of LIFO liquidation 0.06 0.05 0.04 0.03 0.02 0.01 0 ‐0.20 ‐0.17 ‐0.14 ‐0.11 ‐0.08 ‐0.05 ‐0.02 0.01 0.04 0.07 0.10 0.13 0.16 0.19 Quarterly earnings surprises (AFE) 27 Table 1: Descriptive Statistics for LIFO Liquidation and Non-liquidation Samples. LIFO liquidations are identified from text string searches of financial statements (10-Qs and 10-Ks) and earnings press releases (8-Ks) filed with the SEC between January 1, 1994 and April 30, 2008. Liquidations that decrease quarterly earnings, occurred in a previous quarter, or are reported as part of discontinued operations are discarded. Non-liquidation firms are required to have a positive beginning-of-year LIFO reserve of at least 2 cents per share (after-tax) on Compustat and quarterly earnings announcement dates that fall within the liquidation sample period. Regulated utilities (SIC codes 4900-4999) as well as finance, insurance, and real estate firms (SIC codes 600067999) are discarded. Non-liquidation firm/quarter observations where earnings announcement stock returns (day 5 to +5) are not available from the CRSP daily returns file are then discarded. These same sample selection filters are imposed on the LIFO liquidation sample. Liquidation and non-liquidation firm/quarters are pooled to form the LIFO “population” in this table. Panel A: The Frequency of Sample Observations by Fiscal Quarter. LIFO population firm/quarters Fiscal Year LIFO liquidation firm/quarters Q1-Q3 Q4 Total Q1-Q3 Q4 Total 1993 62 565 627 1 74 75 1994 1,969 688 2,657 16 85 101 1995 2,091 712 2,803 7 62 69 1996 2,055 693 2,748 11 78 89 1997 1,913 643 2,556 10 64 74 1998 1,743 579 2,322 7 53 60 1999 1,479 500 1,979 3 54 57 2000 1,375 462 1,837 7 64 71 2001 1,276 423 1,699 8 71 79 2002 1,181 391 1,572 5 69 74 2003 1,105 369 1,474 19 77 96 2004 1,045 353 1,398 30 68 98 2005 994 332 1,326 21 71 92 2006 964 322 1,286 24 64 88 2007 872 267 1,139 22 59 81 Total 20,124 7,299 27,423 191 1,013 1,204 28 Table 1(continued) Panel B: Unrecognized and Recognized LIFO Holding Gains This panel describes LIFO liquidation firms’ unrecognized (LIFO reserve) and recognized LIFO holding gains. Dollar amounts are in millions (except per share) and are adjusted for inflation during the sample period using the Consumer Price Index (December 2007=100). Per share dollar amounts are after-tax and indicate the impact of unrecognized and recognized LIFO holding gains on reported EPS. LIFO reserve amounts are as of the beginning of the fiscal year. Beginning-of-year asset and inventory amounts are adjusted upward by adding the LIFO reserve. Some liquidations dollar amounts are deemed by management to be “not material”. Some liquidations are disclosed only after the fact in later quarter, often in conjunction with another (and larger) contemporaneous liquidation. LIFO Liquidation firm/quarter Q1-Q3 Q4 Total 29.631 29.123 29.421 Median per share amount ($) 0.843 0.729 0.740 % of Sales 0.031 0.023 0.024 % of Assets 0.039 0.032 0.033 % of Inventory 0.186 0.158 0.166 1.333 1.462 1.441 Magnitude of LIFO reserve: Median dollar amount ($M) Magnitude of liquidation gain: Median dollar amount ($M) Median per share amount($) 0.044 0.056 0.053 % of LIFO reserve 0.033 0.043 0.042 % termed "Not material" 0.099 0.179 0.166 % not disclosed in quarter 0.105 0.112 0.110 % disclosed in press release 0.183 0.070 0.088 % disclosed only in 10-K/10-Q 0.712 0.818 0.802 % with Qt-4 liquidation 0.246 0.602 0.546 % disclosed as after-tax amount 0.309 0.534 0.429 LIFO liquidation disclosure: 29 Table 2: Descriptive Statistics for Variables Included in the Earnings Benchmark Probit Regression Tests. This Table describes the sample used in probit regression tests. The sample includes all firms with pre-liquidation quarterly earnings surprises, measured as I/B/E/S “actual” EPS minus the I/B/E/S consensus (mean) EPS forecast between -0.10 per share and +0.09 per share. The after-tax per share LIFO liquidation holding gain is subtracted from the I/B/E/S “actual” EPS for liquidation firm/quarter observations. Firms with “non-material” liquidations where no amount is disclosed are also excluded. Firms are then separated based on whether the quarter includes a LIFO liquidation. Panel A reports means and medians and test of differences between the two samples. Panel B reports Pearson (below diagonal) and Spearman (above diagonal) correlations between regression variables. All variable definitions are included in the Appendix. Panel A: Variable Means and Medians Non-Liquidation Firm Liquidation Firm Quarters Quarters Variable Mean Median Mean Median RATE NOL ∆Sales ∆Salest-1 LOSS LEV LRES LAGLIQ Q4 0.354 0.221 0.100 0.092 0.033 0.259 0.508 0.073 0.242 0.368 0.000 0.071 0.067 0.000 0.246 0.254 0.000 0.000 0.349 0.283 0.063 0.067 0.057 0.240 0.867 0.680 0.829 Between Sample Test Mean t-statistic 0.649 -2.558* 2.980** 2.045* -1.894 2.070* -5.796** -24.221** -28.659** 0.366 0.000 0.036 0.047 0.000 0.220 0.537 1.000 1.000 Median z-statistic 1.056 -2.771** 4.890** 2.942** -2.417* 2.849** -10.487** -39.792** -24.889** Differences in means are tested using a t-test of differences. Differences in medians are tested using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Panel B: Pearson (below diagonal) and Spearman (above diagonal) Correlation Coefficients LIQUID MISS RATE NOL ∆Sales ∆Salest-1 LOSS LEV LRES LAGLIQ Q4 LIQUID 1.000 0.055 -0.009 0.023 -0.040 -0.024 0.020 -0.023 0.086 0.325 0.203 MISS 0.055 1.000 0.020 -0.038 -0.149 -0.054 0.062 0.018 0.024 0.021 -0.006 RATE -0.007 0.016 1.000 -0.121 0.044 -0.011 -0.048 0.007 0.031 -0.026 -0.025 NOL 0.023 -0.038 -0.090 1.000 -0.015 0.000 0.026 0.072 -0.049 0.065 -0.008 ∆Sales -0.015 -0.050 0.019 -0.013 1.000 0.147 -0.117 -0.012 -0.069 -0.047 0.012 ∆Salest-1 -0.017 -0.034 -0.008 -0.004 0.022 1.000 -0.014 -0.094 -0.071 -0.034 0.010 LOSS 0.020 0.062 -0.069 0.026 -0.060 0.021 1.000 0.026 -0.003 0.040 -0.009 LEV -0.018 0.013 -0.023 0.072 0.029 -0.059 0.038 1.000 -0.054 -0.005 -0.023 LRES 0.059 0.118 0.011 -0.023 -0.007 -0.025 -0.008 -0.013 1.000 0.169 0.000 LAGLIQ 0.325 0.021 -0.035 0.065 -0.016 -0.030 0.040 0.005 0.114 1.000 -0.017 Q4 0.203 -0.006 -0.009 -0.008 0.014 0.005 -0.009 -0.021 0.001 -0.017 1.000 30 Table 3: Likelihood of LIFO Liquidations and Benchmark Beating. This table reports the results of probit regression tests of Model 1. . The sample includes all firms with pre-liquidation quarterly earnings surprises, measured as I/B/E/S “actual” EPS minus the I/B/E/S consensus (mean) EPS forecast between -0.10 per share and +0.09 per share. The after-tax per share LIFO liquidation holding gain is subtracted from the I/B/E/S “actual” EPS for liquidation firm/quarter observations. Firms with “non-material” liquidations where no amount is disclosed are also excluded. We re-estimate the regression for a smaller sample of firms with pre-liquidation quarterly earnings surprises between -0.04 and +0.03 cents per share. All variables are defined in the Appendix. 1 Variables INTERCEPT MISS RATE NOL ∆Sales ∆Salest-1 LOSS LEV LRES LAGLIQ Year Indicators AFE between -0.10 and +0.09 Q1-4 Q4 -2.578 0.323 0.096 0.013 -0.208 -0.184 0.071 -0.431 0.058 1.487 Included *** *** * *** *** -2.255 0.426 0.086 0.000 -0.388 -0.147 0.211 -0.418 0.115 2.286 Included AFE between -0.04 and +0.03 Q1-4 Q4 *** *** * *** *** Chisq 848.620 824.380 N 14,631 3,694 ***, **, * indicates two-tailed p-value less than 0.005, 0.01 and 0.05 respectively -2.544 0.230 0.450 0.019 -0.612 -0.130 -0.052 -0.553 0.077 1.470 Included 498.970 9,549 *** *** *** * *** *** -2.410 0.271 0.470 -0.002 -1.031 -0.121 0.146 -0.452 0.131 2.339 Included *** *** *** *** *** 488.490 2,343 31 Table 4: Earnings Announcement Returns and Liquidations For each individual trading day from -5 to 5, Panel A reports the daily size-adjusted returns, where day 0 corresponds to the quarterly earnings announcement date. Panel A also reports cumulative market-adjusted return around (-1, 1) of earnings announcement. Panel B reports the stock market reaction to earnings surprises in the presence of LIFO liquidation. The sample is comprised of all firm-quarter observations with a positive beginning-ofyear LIFO reserve of at least 2 cents per share (after-tax) on Compustat and quarterly earnings announcement dates that fall within the liquidation sample period. Regulated utilities (SIC codes 4900-4999) as well as finance, insurance, and real estate firms (SIC codes 6000-67999) are discarded. Liquidation observations with non-material liquidation, liquidation per share less than $0.005 or greater than $0.10 are deleted. CAR3 is the size-adjusted cumulative abnormal stock return for trading days -1 to +1, where day 0 corresponds to the quarterly earnings announcement date. Liquidation is an indicator variable equal to one if a liquidation occurs. UE_GAIN is the increase in quarterly EPS attributable to the liquidation of that quarter. UE is total unexpected earnings defined as “actual” EPS from I/B/E/S minus the most recent IBES consensus forecast. P is the closing share price for the previous quarter. Growth is an indicator variable that equals 1 when the percentage change in book value of equity for the previous year is above the sample median, and zero otherwise. Size is an indicator variable that equals 1 when the firm is above the median market capitalization for our sample. Beta is CRSP Beta decile rank. Panel A: Mean daily market-adjusted returns for the liquidation and non-liquidation samples. Trading day Non-liquidation firms P-value Liquidation P-value -5 0.0004 0.0335 -0.0012 0.2640 -4 -0.0003 0.1258 -0.0011 0.2482 -3 -0.0002 0.3831 0.0007 0.4640 -2 0.0004 0.0117 0.0006 0.6019 -1 0.0009 <0.0001 0.0023 0.0315 0 0.0016 <0.0001 0.0022 0.3335 1 0.0012 <0.0001 -0.0003 0.8760 2 0.0004 0.0428 -0.0002 0.9017 3 0.0001 0.4946 0.0018 0.1130 4 0.0002 0.1594 0.0003 0.7781 5 0.0005 0.0021 0.0012 0.3094 (-1, 1) 0.0012 <0.0001 0.0014 0.1815 32 Table 4 (continued) Panel B: Stock market reaction to earnings surprises in the presence of LIFO liquidation CAR3 = α0 + α1Liquidation + α2UE_GAIN/P +α3UE /P + α4 UE /P*LOSS + α5 UE/P*Size+ α6 UE /P *Beta + α7UE/P*Growth + ε Quarter 1-4 Quarter 4 P-value P-value Predicted Sign Coefficient (two tailed) Coefficient (two tailed) Intercept 0.0023 <.0001 0.0044 <.0001 Liquidation + 0.0016 0.5994 0.0051 0.1530 UE_GAIN/P -1.7286 0.0058 -1.4598 0.0746 UE/P + 2.2822 <.0001 1.4019 <.0001 UE/P*LOSS -2.0898 <.0001 -1.2961 <.0001 UE/P*SIZE + 0.8958 <.0001 0.7142 <.0001 UE/P*Beta -0.0188 <.0001 -0.0102 0.0455 UE/P*Growth + 0.1263 0.0035 0.0763 0.4771 Adjusted R2 (%) 5.50 3.23 F-value 178.35 27.95 N 21,323 5,653 33 Table 5: Earnings Announcement Returns to Liquidations that Meet or Beat Analysts’ Forecasts For each individual trading day from -5 to 5, Panel A reports the daily size-adjusted returns, where day 0 corresponds to the quarterly earnings announcement date. Panel A also reports cumulative market-adjusted return around (-1, 1) of earnings announcement. Panel B reports the stock market reaction to earnings surprises in the presence of LIFO liquidation. The sample is comprised of all firm-quarter observations with a positive beginning-ofyear LIFO reserve of at least 2 cents per share (after-tax) on Compustat and quarterly earnings announcement dates that fall within the liquidation sample period. Regulated utilities (SIC codes 4900-4999) as well as finance, insurance, and real estate firms (SIC codes 6000-67999) are discarded. Liquidation observations with non-material liquidation, liquidation per share less than $0.005 or greater than $0.10 are deleted. CAR3 is the size-adjusted cumulative abnormal stock return for trading days -1 to +1, where day 0 corresponds to the quarterly earnings announcement date. Liquidation is an indicator variable equal to one if a liquidation occurs. UE_GAIN is the increase in quarterly EPS attributable to the liquidation of that quarter. MISS is one if the firm missed the beginning of quarter consensus forecast, after removing the LIFO liquidation gain. UE is total unexpected earnings defined as “actual” EPS from I/B/E/S minus the most recent IBES consensus forecast. P is the closing share price for the previous quarter. Growth is an indicator variable that equals 1 when the percentage change in book value of equity for the previous year is above the sample median, and zero otherwise. Size is an indicator variable that equals 1 when the firm is above the median market capitalization for our sample. Beta is CRSP Beta decile rank. CAR3 = α0 + α1Liquidation + α2UE_GAIN/P + α α α _ +α6UE /P + α7 UE /P*LOSS + α8 UE/P*Size+ α9 UE /P *Beta + α10UE/P*Growth + ε Quarter 1-4 Quarter 4 Predicted Sign Intercept Liquidation UE_GAIN/P MISS liquidation*MISS UE_GAIN/P*MISS UE/P UE/P*LOSS UE/P*SIZE UE/P*Beta UE/P*Growth Adjusted R2 (%) F-value N + ? ? + + + P-value Coefficient (two tailed) 0.0058 <.0001 0.0002 0.9596 -3.1744 <.0001 -0.0127 <.0001 0.0040 0.5333 5.6473 <.0001 2.1503 <.0001 -1.9365 <.0001 0.8590 <.0001 -0.0207 <.0001 0.1130 0.0087 6.36 144.56 21,140 P-value Coefficient (two tailed) 0.0071 <.0001 0.0059 0.1778 -2.7392 0.0057 -0.0100 <.0001 -0.0008 0.9169 4.1543 0.0178 1.3413 <.0001 -1.2227 <.0001 0.7001 <.0001 -0.0115 0.0243 0.0544 0.6126 3.72 22.25 5,500 34