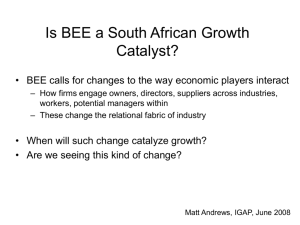

Working Papers Center for International Development at Harvard University

advertisement