D C S

advertisement

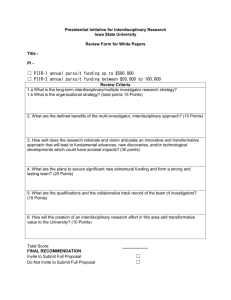

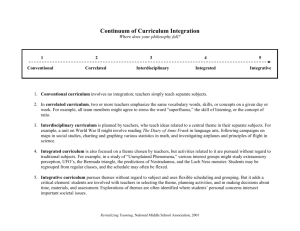

DEFINING COURSE STRUCTURES The term “interdisciplinary” is quite often misunderstood or is taken as some very large and very vague idea. Courses that are often thought of as interdisciplinary are sometimes multidisciplinary, cross-disciplinary or adisciplinary. Below is an effort to distinguish between these structures. I have borrowed Carolyn Haynes’ metaphor of ice cream, which, like these structures, is just basically good—but it comes in many varieties that produce very different results. •MULTIDISCIPLINARY courses present disciplinary perspectives in a serial fashion, like Neapolitan ice cream. The flavors/discipline contents are lined up next to each other but don’t intersect. While this is an interesting approach, it leaves the responsibility of integrating the knowledge up to the students. •CROSS-DISCIPLINARY courses are courses in which one disciplinary perspective dominates the other(s), like chocolate chip ice cream, where the dominant flavor is vanilla but with flavorful little chunks sprinkled throughout. While courses can be intentionally designed to be cross-disciplinary, cross-disciplinarity can also be an accidental result if the class is taught by one person, or if one discipline’s “way of knowing” is the focus with nuggets of a second (or third or fourth) discipline’s content scattered across the material. •ADISCIPLINARY courses attempt to gain a holistic picture without specific attention to disciplines. A course like this generally starts with an idea and the approaches pop up where they may, like tutti-frutti. This is an interesting idea, but it can leave students (and faculty) feeling insecure and without direction. Because there is not a conscious effort to integrate types of knowledge, interdisciplinarity is generally missing. •INTERDISCIPLINARY courses work toward conscious integration of insights from disciplines. The result is like marble ice cream, where both flavors/disciplines remain distinct and equal, but the result is a distinctly new flavor/experience. This handout addresses only interdisciplinary courses. INTERDISCIPLINARY FACULTY Character Traits: •Patient Working with another faculty member requires some patience, but it’s worth it. Teaching students who don’t always get what we’re trying to do requires patience as well, but that, too, is worth it. •Flexible Being part of a team means doing things a little differently. In addition to that, the really successful interdisciplinary courses often change considerably during the semester. That’s a good thing. •Resilient This isn’t easy. It requires trying new things that are sometimes wildly successful and sometimes . . . not. Sometimes it’s from the mistakes that both faculty and students learn the most. •Risk-takers The idea of interdisciplinary teaching, particularly as a team, is new to most of us. Perhaps the fact that we must give up the coverage model is the scariest thing for us, but teaching a class that will end somewhere unknown can also require some risk. It will keep the blood pumping. •Sensitive to others Teamwork requires sensitivity, and we also need to recognize that working with students and faculty from other disciplines isn’t always easy for our students, either. •Have a preference for diversity Folks who like doing the same thing in the same way every day with the same type of people probably shouldn’t attempt this. •Willing and able to work well with others Team teaching takes some doing, and not just in the planning stages. It’s a semester long commitment to working closely with a peer. That’s the good news, but it can also be work. WORKING AS A TEAM •Address personality differences head-on. Personality differences can be difficult, but they can also be the brightest spot in the experience. If your styles differ, find ways to use that to your advantage. To do so, you have to talk about it honestly. •Overcome disciplinary biases. We all have them, but team teaching requires that all members respect each other’s discipline. This usually requires fairly constant maintenance. •Discuss educational philosophies of team members. Don’t assume you have the same ideas or goals. Talk about it. It may be a ten minute conversation, or it might require days. However long it takes, it will save you time and energy in the long run. •Overcome status differences. Our interdisciplinary courses are taught by teams of qualified faculty who express interest in the project—without regard to rank. If a tenured full professor and a new part-time lecturer are co-teaching, they are equals in the enterprise. •Be aware of student game-playing. Shocking news, but a few students will try to play faculty off one another. Be aware and nip it. However, some students simply don’t get what, how or why we do this. We often see SETEs with comments something like “I’m a philosophy major, not an archeology major. Why do I have to do dig in the dirt?” That’s why it’s so important to talk with students about what you are doing pretty much every step of the way. PUTTING TOGETHER A COURSE • Identify pertinent disciplines and assemble a team. Try to ensure equal participation among members. • Develop a topic; consider how to balance breadth and depth. Unlike discipline curricula that depend on individual classes providing discrete chunks of knowledge that a student uses to build on from one year to the next, interdisciplinary courses are worlds unto themselves. That is one reason why focus is so very important. Do not try to cover a huge topic; instead, focus on one part of the topic or one part of a problem. Some interdisciplinary courses have been built on a single statement. For instance, one course (syllabus available on the AIS website) used a statement, made in an article that was assigned as the first reading, that the problems present in the Middle East today are directly linked to the Crusades. That gave the class focus and two points of reference—the Crusades and a current, changing situation. The topics covered in the class include political science, religion, geography, mythology, literature, weaponry, etc. A course we could do here might be building a sustainable, “green” campus. Virtually all disciplines could be involved, and it could culminate in a proposal that would have lasting value. • Let go of the “coverage” model. This is important and difficult to do. Unlike our disciplinary courses, where we generally have a certain body of knowledge to cover in a class, interdisciplinary courses take models, approaches, and ideas from more than one discipline to address a problem, issue or idea. The point is to go into uncharted territory, not to go deep into the heart of any one discipline. Give them as much as they need to do what they will do for the class and let the rest go. • Consider what the course is really about (subtext). This is important for a couple of reasons. One is to ensure focus and clarity, and the other is to make sure you and your teaching teammate are really on the same page. • Identify outcomes. There is a list of outcomes in this handout, but yours may be different, and they will no doubt be more specific. Knowing where you’re trying to go as a team is very important to the success of an interdisciplinary course. QUESTIONS TO GUIDE INTERDISCIPLINARY COURSE PREPARATION •Is the course issue-based (societal problem, historical moment, text, geographical region, or key concept)? •What question about the issue is the course designed to explore? •What makes the question appropriate to ID inquiry? •Is the issue focused (few enough sub-issues for students to understand perspectives on the issue and develop facility with concepts, theories, and methods introduced)? •Are the perspectives of disciplines/schools of thought explicit? Are respective contributions to the issue explicit? •How dominant is one discipline? Do less-dominant disciplines provide more than subject matter? •Is the level of the course consistent with depth of disciplinary perspectives, explicitness of assumptions, sophistication of disciplinary tools, explicitness about ID methodology, balance of breadth and depth? THE SYLLABUS • Go over the syllabus in detail the first day. It’s a good opportunity to inform students about the structure of the class. Many/most of our students are surprised by these classes; they come in year three, after fourteen or fifteen years of straight disciplinary classes. • In the syllabus, explain how the course is interdisciplinary. It seems that most students actually expect a multidisciplinary or (more often) a cross-disciplinary class, in which they can still stay in the comfort zone of their own majors and just receive information about some other discipline. Tell them how the course is structured to integrate multiple disciplines. Do this orally and in detail on on the syllabus. They’ll need to be reminded. • In the syllabus, explain why the course is interdisciplinary. For interdisciplinary courses, it’s a good idea to make the outcomes section of the syllabus a major part of the document. Students tend to enjoy these classes, which is good of course, but they need to be able to articulate for themselves the reasons why the experience should be a significant part of a serious educational endeavor. • Explain how the course will help students meet goals of the university and prepare them for professional and private life. • Make course design, organization, disciplinary contributions, outcomes and assessment explicit. TEACHING THE COURSE • Meet regularly throughout course to reflect and plan. One way to assess the effectiveness of these courses is to ask if attitudes, approaches, or assumptions changed during the semester—for the faculty as well as the students. Meeting regularly will make those changes easier, and it’s stimulating and fun for us. Really. • Model good teamwork and integration in front of the students. That doesn’t mean you will always agree. Respect and interest in the other way of thinking is necessary, but differing opinions and attitudes can be energizing. • Use differences in viewpoints as learning opportunities for students. Our students will benefit from our modeling intellectual discussions based in respect, even when opinions differ. • Reinforce and support one another as much as possible. ASSUMPTIONS AND TERMINOLOGY • Be aware of implicit as well as explicit assumptions. • Assess appropriateness of assumptions to context. • Seek underlying similarities in differing terminology. • Seek underlying differences in similar terminology. • Determine if conflict (in concepts or assumptions) is • agreement obscured by a difference in terminology, • differences between alternatives, or a • clash between polar opposites. LEARNING STRUCTURES: The Association for Integrative Study has done studies on heuristics that work well in interdisciplinary classes. Here are a few of their suggestions. (This list isn’t meant to be definitive.) Formal Cooperative Learning Structures Group work is particularly effective in integrative classes. •Student Team Achievement Division (STAD): A heterogeneous group works together to complete a teacher-designed assignment. •Jigsaw: Each group member is given a specialized discipline area and must contribute to the teacher-designed ID assignment. •Group Investigation: The teacher presents an ID problem; groups must come up with their own plan to address the problem using multiple disciplines. Inquiry Based Learning An orientation toward learning that is flexible and open and draws upon the varied skills and resources of the faculty and students, in which faculty are co-learners who guide and facilitate the student-driven, interdisciplinary learning experience. Service Learning Service Learning is a teaching and learning method that enables students to link theory with action through guided reflection. It connects students to members of a community where they provide meaningful service that responds to community needs as defined by the community. For a service learning experience to work, it should include: •Ethical and meaningful collaboration with the community, •Meaningful integration of service into the course, •Ongoing reflection on the ethical, intercultural and interdisciplinary implications of the service experience, •Integrative journals. These work best if they are more than diaries. Evaluating journals can, however, be incredibly time consuming and not that productive for the faculty or students. A good suggestion is to have the students do journaling (in one of the professional styles) with responses to course driven prompts or problems, and then have the students evaluate each others’ work. They learn a great deal from both ends of that experience. (Articles on journal work in courses will soon be available from CIIS.) AT THE COURSE END, STUDENTS SHOULD BE ADEPT AT: • • • • • • • • Identifying conflicts in insights; Resolving conflicts in insights; Evaluating assumptions and concepts in context; Creating common ground/vocabulary; Identifying linkages between different disciplines; Producing models/metaphors/themes; Constructing a new understanding of the problem; Testing understanding by attempting to solve the problem. OUTCOMES • • • • • • • • • • • • Critical thinking Analytical thinking Writing with clarity and precision Research skills developed/improved Deepened understanding of the issue(s) Rethinking of ideas taken for granted Investigating various sides of an issue Effectively evaluating resources Recognizing ambiguity and biases Developing ethical sensitivity Synthesizing or integrating ideas Enlarging horizons or perspectives ID STUDENT CHARACTERISTICS These are the characteristics that both employers and graduate schools have said they would like to see in their applicants. (AIS survey) Interdisciplinary studies is one of the best preparations for achieving these results. • Asks questions • Determines goals and meets them • Open-minded, independent thinker • Adaptable, not afraid to try new things • Creative and innovative • Adapts textbook knowledge to the real world • Continues to grow and learn • Skills: • Problem-solving • Research • Writing • Oral communication • Listening • Team-spirited, understands group dynamics, works well in group settings, willing to help others • Sees the big picture (not just an area of specialization) • Diversity-aware, treats others with dignity and respect DID IT WORK? At the end of the course, evaluate your experience. (And please share it with the rest of us.) • Did faculty tend to work together, not just alone? • Did they interact instead of merely working jointly? • Did the issue of the course shift as the course evolved? This is a good thing! • Have faculty perspectives on the issue/problem been altered through the process? Another good thing! • Have connections to complementary pedagogies— collaborative learning, critical thinking, learning styles/stages, multiculturalism—been made? THE IRON LAW “Students shall not be expected to integrate anything that the faculty can’t or won’t.” (Jonathan Z. Smith) REFERENCE MATERIALS • • • • AIS Website at http://www.units.muohio.edu/aisorg Sample course syllabi at http://www.units.muohio.edu/aisorg/syllabi/index.html CIIS has collected previous CSUCI ID course syllabi, which are available for checkout. (Please note that many/most of these are currently being revised.) If you need help finding resources, contact Carmen Delgado at 437-3272. She and the CIIS part-time AA will be happy to help you locate and (if necessary and possible) purchase what you need. PUBLICATIONS AVAILABLE (OR SOON TO BE AVAILABLE) FROM THE CENTER FOR INTEGRATIVE AND INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDY 2005: Allen Repko, Interdisciplinary Practice: A Student Guide to Research and Writing. Pearson Custom Publishing 2005: Tanya Augsburg, Becoming Interdisciplinary: An Introduction to Interdisciplinary Studies. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt. 161 pp. ISBN: 0-7575-1561-4. Provides a scholarly overview of interdisciplinary studies and helps students to recognize themselves as interdisciplinarians. The first published undergraduate introductory textbook in interdisciplinary studies, it introduces students to the importance of interdisciplinary research and problem solving. Also includes seminal texts in interdisciplinary studies. This text is geared toward an interdisciplinary first-year experience course, but it contains helpful information for any ID teacher. 2002: Carolyn Haynes (ed.) Innovations in Interdisciplinary Teaching. American Council on Education, Series on Higher Education Westport, CT: Oryx Press/Greenwood Press. 295 pp. ISBN: 1-57356-393-5 Essays on the special challenges and opportunities of innovative teaching practices in the context of interdisciplinary courses. Each chapter is on a specific teaching innovation, written by one of its leading proponents. Innovations include team teaching, writing across the curriculum, learning communities, computer-assisted instruction, performance, study abroad and more. 1998: William H. Newell (ed.), Interdisciplinarity: Essays from the Literature. New York: The College Board. 563 pp. ISBN: 0-87447-600-3 An anthology of key articles and chapters drawn from the professional literature on interdisciplinary studies. Sections focus on the overall nature and practice of IDS, philosophical analyses, administration, the relationship of IDS and the disciplines, IDS in each area (social sciences, humanities and fine arts, and natural sciences) and in specific interdisciplinary fields. Includes a synthesizing essay that sets out a research agenda on interdisciplinarity. 1990: Julie Thompson Klein. Interdisciplinarity: History, Theory, and Practice. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. 331 pp. ISBN: 0-8143-2087-2 A milestone in books in interdisciplinarity. This encyclopedic overview of the interdisciplinary landscape focuses on the nature of interdisciplinarity, its relationship to disciplines, and its practice in health care and research as well as higher education. It concludes with a 94 page bibliography. 2002: Julie Klein (ed.), Interdisciplinary Education in K-12 and College: A Foundation for K-16 Dialogue. New York: The College Board. 216pp. ISBN: 0-87447-679-8 Brings together K-12 and higher education luminaries to examine the continuum of interdisciplinarity in American education. The latest of four books in the College Board series on foundations, resources, and practices in interdisciplinary education. 1999: Marcia Seabury (ed.). Interdisciplinary General Education: Questioning Outside the Lines/ the University of Hartford Experience. New York: The College Board. 366pp. ISBN: 0-87447640-2 (hardcover), 0-87447-639-9 (paperback) Addresses common concerns of faculty new to interdisciplinary course development and teaching in general education, in general terms and in the context of specific courses. It gets beyond generic issues to the practice of interdisciplinarity, confronting concerns that are emotional as well as intellectual. In the process, it presents designs for courses on a wide array of topics. 1996: Julie Thompson Klein. Crossing Boundaries: Knowledge, Disciplinarities, and Interdisciplinarities in the series on Knowledge: Disciplinarity and Beyond. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia. 281 pp. ISBN: 0-8139-1679-8 Boundary Crossing An extended examination of the claims that knowledge is increasingly interdisciplinary and that boundary crossing has become a defining characteristic of our age. The chapter on interdisciplinary studies focuses on urban and environmental studies, border and area studies, women's studies and cultural studies. 1995: James R. Davis. Interdisciplinary Courses and Team Teaching: New Arrangements for Learning. ACE Series on Higher Education. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press (now an imprint of Greenwood Press). 271pp. ISBN: 0-89774-887-5 Explains the benefits and pitfalls of interdisciplinary team-taught courses and provides practical information on how to design and conduct them. It includes a listing of nearly 100 interdisciplinary, team-taught courses in general education, women's and gender studies, professional and technical programs, and electives.